What I learned about the Holocaust playing a game called ‘Gestapo’

There is no good strategy for choosing when to risk family, community, religion, civil liberties and life itself

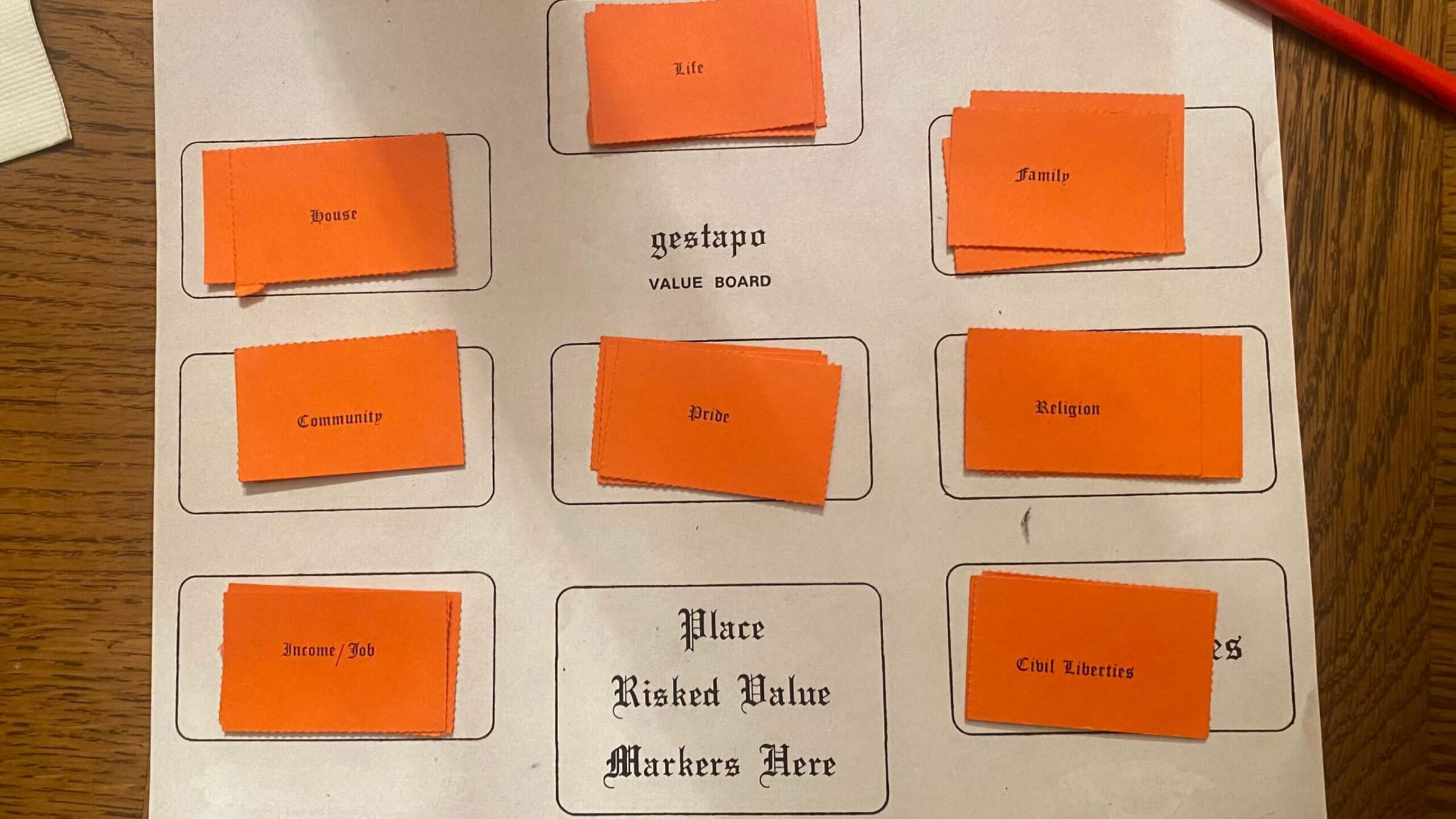

The simple, if slightly tone-deaf, game board of “Gestapo: A Game of the Holocaust.” Photo by Gary Rudoren

This is an adaptation of Looking Forward, a weekly email from our editor-in-chief sent on Friday afternoons. Sign up here to get the Forward’s free newsletters delivered to your inbox.

The worn cardboard box unearthed this summer from a chaotic storage room at my suburban synagogue is labeled, in felt tip, “Gestapo Game.” Inside are bingo-style boards that distill what our forebears risked and lost in the Holocaust to eight “values”: Family, House, Community, Religion, Civil Liberties, Income/Job, Pride and Life itself.

Shocked, horrified, and also intensely curious, my friend Josh Katz, our synagogue president, brought the box over to my place for a surreal sort of game night. We played with my husband and 14-year-old twins, Josh’s about-to-be-bar-mitzvah son, Benny, and a journalist friend who might fairly be described as obsessed with historical trauma. When we saw on the instruction sheet that the game allowed for four to 1,000 players, someone joked that the upper limit should have been set at 6 million.

It was not, shall we say, fun, but it was also not as bad as we expected. It might even be a little bit brilliant.

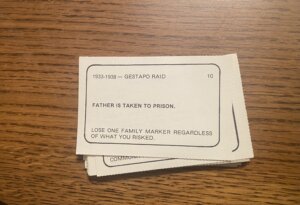

“Gestapo: A Game of the Holocaust” was created in 1976 by a rabbi and a Jewish educator who ran Alternatives in Religious Education, a little company that pumped out pamphlets about life cycle events, holidays and history. It was meant to be educational, not fun, of course, and in some ways is not really even a game — the instructions lack the usual “How to Win” section.

Each person starts with three cards for each of the eight values, and on each turn has to choose which value to risk. The turns consist of someone reading cards with, as the instructions say, “specific (and true) events” that occurred between 1933 and 1945, in chronological order.

The cards help break down the overwhelming, horrific history into more absorbable, even relatable bits: “Hitler comes to power in Germany”; “The Talmud, Torah and other Jewish books are burned by the Nazis”; “Jews are barred from eating in public restaurants”; “In the ghetto, the birth rate plunges toward zero”; “Emigration of Jews to free lands is stopped”; “When Jews arrive at a death camp, families are separated.” Some are particularly personal: “FATHER IS TAKEN TO PRISON;” “Your son has been taken by the Gestapo and charged with smuggling food into the ghetto”; “YOU HAVE BEEN SELECTED BY THE NAZIS TO BE A KAPO.”

I started out thinking that preserving my “Life” cards was most important, but soon realized, since the early Nazi attacks were on civil liberties, religion and pride, the better strategy is actually to risk “Life” early on. Then — and here’s the little bit of brilliance — you realize that, as in the actual Holocaust, there really is no reliable strategy. When you get to the Wannsee Conference, where the card “a final solution of the ‘Jewish Problem’ is planned,” for example, the instructions are: LOSE ALL RISKED MARKERS.

‘The idea is interesting … but it doesn’t feel right’

WHAT WERE THEY THINKING was what we all kept thinking about the makers of the game, which was pilloried in a 1980 New York Times article where Elie Wiesel said such supposed educational materials “dishonored the victims and rendered the public insensitive to the tragedy.”

So we tracked down Rabbi Raymond A. Zwerin, who created “Gestapo” along with Audrey Friedman Marcus, his partner in the publishing company, after a public-school teacher named Leonard Kramish came to them with the idea for a trivia game about the Holocaust.

“I said the idea is interesting, Len, but it doesn’t feel right,” recalled Zwerin, who is now 85. “You can’t ask questions about the Holocaust. The Holocaust isn’t about statistics. It’s about people moving, it’s about the destruction of the human spirit, it’s about man’s inhumanity to others.”

“So ultimately, this game is about saving your life, this game is about surviving,” he added. “But the cards can’t be questions, they have to be statements of fact.”

Zwerin was ordained by Hebrew Union College in 1964 and three years later started a synagogue in Denver that by his retirement in 2005 had 1,165 families. He told me a long, detailed history of the little publishing company, which he framed as largely a response to a tumult at the 1972 General Assembly, when as he put it, “hundreds of young Jewish kids came marching in” and demanded “that they stop using junk materials in religious schools.”

I was intrigued, as it reminded me of a more recent generation’s complaints about the one-sided nature of much of what synagogue schools, camps and day schools teach about Israel. “All of Jewish educational materials until about 1970 was the same as before World War II,” Zwerin said. “In the 1960s, there was a revolution in education in the public schools, but Jewish schools were still using outdated materials.”

He and Friedman Marcus, educational director at another Denver synagogue, started meeting on Thursdays, his day off, to type up “mini-courses” that he described as “self-motivating pamphlets” in which students “would answer questions or fill in the blanks or have to discover somehow.”

A modest seller

The first 500 copies of the Gestapo Game sold out in three months, at $8 a pop, Zwerin said. Then the Red Cross of New Zealand ordered 1,000 copies — he thought it was a typo, but officials assured him they wanted to put one in every Red Cross center in their country as well as Australia. He said the game continued to sell, perhaps 100 a year, until 2006, when the publishing company itself was sold (it is now part of Behrman House, perhaps the nation’s largest seller of Jewish educational books).

Overall, he estimated, there were perhaps 6,000 copies, many likely now buried in synagogue storage closets.

“I took the game to a couple of college campuses, I did it for youth groups, I did it for my confirmation class every year for 20 years, I did it at board meetings,” Zwerin said. “Any time there was a group of 20 or more people. With 20 or more people the results of the game were always the same. There was a percentage that survived, and that percentage was exactly the percentage that survived in Europe” — 33%.

I asked him about that 1980 Times article, in which a member of the American Association for Jewish Education called the game an example of problematic curriculum that turns “classrooms into concentration camps.” Zwerin acknowledged that calling it a game might have been a mistake but said he never heard such criticism from anyone who actually played the game — or from his wife, a Holocaust survivor herself, who sold and packaged thousands of copies of it.

“The Holocaust was not a game that you could play, it was ‘Oh my God, how do I get out of this,’ and there was no getting out, it was all about mazel, not saichel, mazel,” he said, using Hebrew words that mean luck and smarts. “I think about my wife’s situation. Her parents were killed, her sister was killed, and she escapes. Somebody found her on the street, as a little kid, and got her to the right ship at the right time. Total mazel.”

‘I can’t throw this away’

The copy of the game I played was discovered as part of a summer-long purge project initiated by Rabbi Sharon Litwin, who just took over as educational director of our synagogue, Temple Ner Tamid in Bloomfield, New Jersey. With a teenage assistant, she’s given away thousands of old books, and organized thousands of others, finding a time capsule of treasures along the way.

There was a bin of perhaps 50 asimonim, the tokens used for Israeli pay phones until 1990. There was a pile of pristine envelopes with a canceled Israeli stamp reading “from the visit of Jimmy Carter to the State of Israel 1979.” There was a placemat from an Israeli kosher McDonald’s with a picture of Ross and Rachel from “Friends.” There were “Keep Abortion Legal” posters from rallies in the 1980s and, as Litwin put it, “many, many multiple copies of the Jewish calendar that the funeral home dropped off in 1989.” And there was this mysterious box that had GESTAPO GAME hand-written on its cover.

“I thought, ‘I can’t throw this away,’ it’s too much like nostalgia or crazy, somebody else needs to see it,” Litwin said. “I brought it up to the library, was going to put it on a shelf with other games, then I looked at it and thought, ‘I can’t put this on a shelf.’ It’s in such poor taste.”

Litwin said she’d never heard of the Gestapo Game, but recalled being shown documentary footage of the gas chambers in Hebrew school at the Teaneck Jewish Center back in the 1980s. “It’s so not the way we teach about the Holocaust in 2022,” she explained. “My training, from Yad Vashem, is ‘safely in, safely out.’ You bring in a story or a situation so that the kids don’t feel unsafe about it. They don’t feel they could be in danger.

“It’s more about survivors than it is about the concentration camps,” Litwin added. “You’re always just trying to protect their mental health. In the world today, we’re so much more protective of our children.”

The mention of Yad Vashem reminded me of the Nazi-propaganda board games from the 1930s I’d seen on display there, filled with antisemitic canards designed to stoke hate and dehumanize Jews in the minds of German children.

The Gestapo Game is basically the opposite of that. It’s a game designed by Jews mainly for Jews, filled with stark, straightforward truths — and teaches the larger, essential truth of the Holocaust: that no strategy could keep you safe.