“Three Minutes”: a 1938 film shot in Poland sparks connection among 300 descendants of a lost Jewish community

The faces of the children follow you in the film, hauntingly, because you’ll never know most of their names.

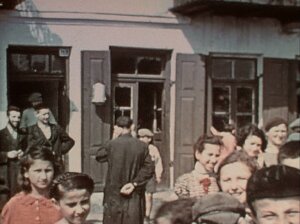

A single frame from David Kurtz’s 1938 footage of Nasielsk, a small town in Poland. Courtesy of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Gift of Glenn Kurtz

This is an adaptation of Looking Forward, a weekly email from our editor-in-chief sent on Friday afternoons. Sign up here to get the Forward’s free newsletters delivered to your inbox.

The faces of the children follow you as you watch the haunting documentary “Three Minutes: A Lengthening.” They keep popping up in the worn frames of the rare 1938 footage from a Jewish neighborhood in a small town in Poland, and the silent footage is played over and over and over again throughout the 70-minute film. The children look straight at you as you sit in your comfortable seat in a suburban movie theater in 2022, thinking of your own children’s faces as you watch these children whose names you will never know.

There’s the girl in the faded red dress. The one with the braids, who pops up so often that at one point, a teenage bully shoves her from view. The boys in their newsboy caps. The girl in the faded red dress again, her hair in the neatest of bobs. Those braids.

They are smiling, jockeying for position, staring in wonder at this strange new thing, a movie camera, and behind it an American visitor. They are smiling because, unlike you, they have no idea what is about to happen to them. They do not know that in a year they and their friends, their parents and their grandparents and all the 3,000 Jews in this little town, Nasielsk, will be marched from the town square and squeezed into cattle cars. They do not know that all but a handful of the scores of faces in this film will soon be erased from this Earth, slaughtered at Treblinka.

They know only that there is a camera, and that they want to be seen. They are children, after all.

From ‘home movie’ to documentary

Glenn Kurtz was a child, too, when he first saw this footage. It was the 1970s and he was growing up in his own comfortable suburb — Roslyn, N.Y. — and remembers his parents showing it to him a couple of times. The footage was shot by his immigrant grandfather, David Kurtz, who ran a company that manufactured boys’ shirts and died before Glenn was born. It was part of a 14-minute travelogue of a European adventure that included Paris, Amsterdam, Geneva and the south of France.

“We just watched it like a home movie,” the younger Kurtz recalled when we spoke by phone yesterday. “No one thought of it as anything other than grandma and grandpa’s vacation footage.”

Decades later, in 2009, Kurtz was working on a novel about someone who finds an old home movie in a flea market and becomes obsessed with identifying the people in it. He went to his parents’ home in Florida and dug the footage out of the back of a closet. It was all but ruined by the years, but U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington miraculously restored the film, and Kurtz posted it online as he, like his character, became obsessed with identifying the people in it.

Back then, no one even knew which town in Poland was depicted. Years of meticulous research resulted in Kurtz’s 2014 book, “Three Minutes in Poland,” and then this remarkable documentary directed by Bianca Stigter, which debuted a year ago at the Venice Film Festival and was released in theaters on Aug. 19.

It also led to the creation of the Nasielsk Society, an informal network of 300 descendants of the few survivors from this town. Last year, the group helped erect the first memorial to the thousands of Jewish residents lost in the Shoah, and Kurtz has been working with teachers in Nasielsk to bring the town’s lost Jewish history into school curriculums.

A context for lives lost

Over the years, a handful more artifacts have been uncovered from Nasielsk, most recently a 1937 photo from the town’s yeshiva that includes Maurice Chandler, one of the boys in the newsboy caps in the Kurtz footage, and one of two survivors whose voices you hear in the documentary. A professor in Amsterdam who works with facial recognition software is hoping to match other faces from the yeshiva photo with those faces following the camera in “Three Minutes.”

“That’s what this project has been about — just connecting these fragments that are floating around in isolation in someone’s drawer or in an archive somewhere,” said Kurtz, who is 59. “The hope is that the more pieces we’re able to assemble, the closer we’re able to come to identify someone or at least to being able to provide a context for their lives.”

The footage he’d viewed as just another home movie as a child looked different once he “became an adult with a historical consciousness,” Kurtz explained. “I inherited this film, and the minute I saw it, I thought, ‘I am responsible for the memory of these people. If I don’t figure out who they are probably no one will and their memory will be lost.'”

So far, only about a dozen of the 153 faces in “Three Minutes” have been identified, despite intense effort. The documentary showcases this effort, with a walk-through of the painstaking process Kurtz and others pursued to determine the name of the owner of the grocery store shown in his grandfather’s footage.

Not far from the synagogue — which itself was identified by the carving of a Lion of Judah on one of its doors — the film shows a doorway with a small sign over it that says “Grocery” in Polish. The letters on the sign that would indicate the proprietor were unrecognizable due to the graininess of the footage, and time. A Polish researcher took the shapes of the least washed-out letters — the first one had a loop at the top so could have been a P, B or R; another was almost certainly a W — and pored through business directories from the time to ultimately determine that the store was owned by someone named Ratowski.

It is satisfying, even a little thrilling, to see this small mystery solved before your eyes. Though we would be fooling ourselves to think that knowing the name of the owner of the grocery store owner means we understand the horror of what happened to him any better.

And later in the film, when Stigter pulls thumbnail portraits of everyone who appears for even a single frame in the original footage into a 17 x 9 grid, it’s clear that there are many, many more names we do not know, will almost certainly never know.

To Nasielsk, with camera in hand

The camera Kurtz’s grandfather carried with him on his European adventure was a Ciné-Kodak Magazine 16 mm introduced the year before, in 1937. More than 70 years later, his grandson bought five of them on eBay for between $25 and $40 each.

“I learned quite a bit by having it in my hand,” he told me. “The whole thing is the size of a paperback book. It’s a spring-wound motor. You wind it up and that provides the power for the motor. The spring has a limited tension, so the longest shot that you can make depends on the strength of the spring.”

For his grandfather’s camera, that was about 20 seconds. Which explains why the three minutes is mainly made up of what feels like a loop of short spurts panning a crowd of faces, the children seemingly chasing the camera as it moves along.

Kurtz took his new-old cameras with him to Nasielsk in 2014, the year his book was published and the 75th anniversary of the deportation of the town’s Jews. Some 50 descendants of the few survivors, or relatives of people like his grandfather who had left Nasielsk before the war, returned as well, the largest group of Jews to grace the town since that fateful day in 1939.

“There’s something about the nature of this history that makes people from the same town feel connected in a real way,” Kurtz said. “People in the film are undoubtedly relatives of mine, though I can’t say who. It feels like an extended family.”

I am responsible for the memory of these people. If I don’t figure out who they are probably no one will and their memory will be lost.

Kurtz, who has a doctorate in German studies and comparative literature from Stanford, had previously written a memoir about his journey as a musician, and from 2008 to 2015 hosted “Conversations on Practice,” a series of discussions of the writer’s life with authors including Patti Smith, Jennifer Egan, Martin Amis and Adam Gopnik.

He’s visited Nasielsk eight times over the last decade, showing his grandfather’s footage at schools and libraries, and last year screening “Three Minutes: A Lengthening” in the town theater for a crowd that included the mayor.

Kurtz is also now president of the Nasielsk Society, which he sees as a third iteration of the “landsmanshaftn,” the networks of immigrants from the old country that were active in New York City in the early 1900s and the period after World War II.

During the 2014 visit with the 50 other Nasielsk descendants, he shot some footage on the Ciné-Kodak Magazine 16 mm. He said he hopes to someday use that footage in another documentary. For now, “it’s in my closet,” Kurtz laughed. But not to worry: “It’s on my computer as well.”