Looking ForwardWould a real mensch wear a ‘mensch’ T-shirt?

I had to practically force the husband to wear it. But then I went down several satisfying rabbit holes.

Image by Google Images

This is an adaptation of our editor-in-chief’s weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox on Friday afternoons.

At a Jewish conference in Chicago last month, I picked up a T-shirt for the husband with a single word on it: mensch.

I liked the sans serif font and the sleek simplicity of the no-caps, white-on-black design. He really is a mensch — good-hearted, thoughtful, honest, humble. He’s also a high school teacher, and kitschy, ironic T-shirts are part of his daily uniform (“Does this shirt make me look bald?” is my son’s favorite). Plus, it was free.

But weeks passed without him putting it on. And when I suggested that it might be perfect for our “open sukkah” party, he hesitated.

“I love the gesture,” he said. “It’s possibly my favorite compliment. But it feels weird to wear it. I don’t know of anybody who’s actually a mensch who would declare themselves a mensch out loud. It would almost be better if it said, ‘Someone who thinks I’m a mensch got me this shirt.’”

As you can see above, I prevailed. It was a safe space — our backyard — and he didn’t get any weird looks or comments. Still, he told me he’s unlikely to ever don it again.

“I wore it because you asked me to,” he explained. “I just don’t think ‘mensch’ is a compliment anyone calls themselves.”

The internet suggests he is wrong. A Google images search reveals a hot market for mensch T-shirts: in English, in Yiddish, in that weird faux-Hebrew font and a font that evokes baseball jersey; with the dictionary definition, “100% Mensch,” “M is for Mensch,” “Bestest Mensch,” “Mensch in Training,” “Daddy’s Little Mensch.”

Somebody must be wearing these.

And this, dear reader, was just the first of many mensch rabbit holes I dove down this week. It was, if nothing else, a nice distraction from the bleak state of the world.

First I had to find out who made the husband’s T-shirt. Turns out it was a software company called Daxko, which provides membership portals for many of the country’s Jewish Community Centers.

Joanna Stahl, who Daxco hired this summer to manage its JCC account, smartly deduced that a shirt with the company’s logo was unlikely to get much traction at the JCC conference. She started brainstorming ideas with the marketing team on Slack.

Among the rejects: Make hummus not hate. Always on. Be the light.

Then Stahl hit on “mensch.” Back in Hebrew school at Temple Beth Shalom in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, when she was about 10, she’d won the “menschlichkeit” award and “the word just resonated,” she told me.

“In my brain, it’s the choice to be a better kid, to pay it forward, don’t be a jerk, if you have a choice to help out somebody in an authentic way, you should and you can,” Stahl explained. She’s given out about 500 of the shirts at various events so far. “It drew people in enough to say ‘this made me feel good, let’s talk.”

“It feels weird to wear it. It would almost be better if it said, ‘Someone who thinks I’m a mensch got me this shirt.’”Gary RudorenMensch

Mensch — along with chutzpah, kvetch and shlep —is one of the Yiddish words most integrated into English. And it’s gotten new life lately, with Jewish Democrats campaigning to make Vice President Kamala Harris’ Jewish husband, Doug Emhoff, the first “First Mensch” (Yes, there are plenty of T-shirts about that, too.)

Merriam-Webster’s “Time Traveler” website says the word first showed up in print (in English) in 1856. The Oxford English Dictionary puts the “earliest known use” at 1911, in the work of the British-American (and Jewish) lawyer and writer Montague Mardsen Glass. “Nowadays, if a feller wants to make a success,” says one of his characters, “he must got to wear good clothes and look like a mensch, y’understand?”

OED goes on to cite usages by Saul Bellow in 1953 (Adventures of Augie: “I want you to be a mensch”); Harold Pinter in 1959 (The Birthday Party: “You’ll be a mensch… You’ll be a success”); and Anne Bernays in 1989 (Professor Romeo: “He decided then and there to be a mensch.”). Leaving popular culture for politics, it offers a 1970 article in New Statesman: “Mr. Nixon is seen as an essential decent man…but not as a mensch on the scale of Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Kennedy.”

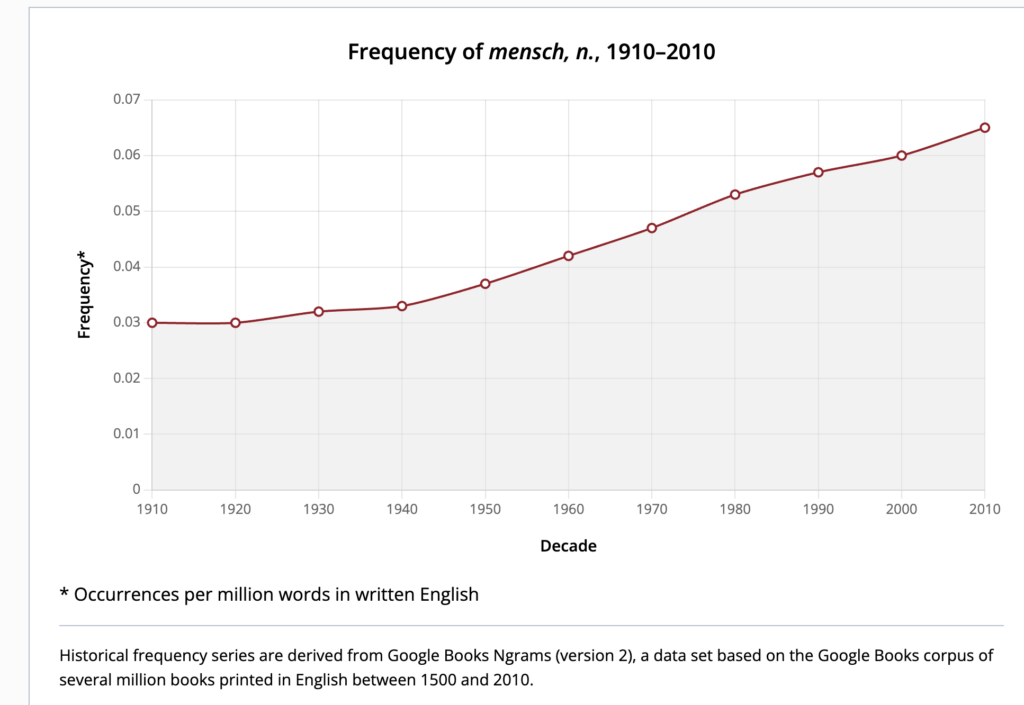

“Mensch” is used about 0.06 times per million words in modern written English, according to something called Google Books Ngrams, which shows the word’s usage doubled between 1910 and 2010. That puts it in the OED’s Band 3 — out of 8 — of frequency, along with 1 in 5 of all words. Only about 17% of English words are used more often,

Some other Band 3 words are merengue, amortizable, cutesy, dirt-cheap, emote, mosey and bad-ass.

“These words are not commonly found in general text types like novels and newspapers,” OED explains, “but at the same time they are not overtly opaque or obscure.”

The OED defines mensch as “a person of integrity or rectitude; a person who is morally just, honest, or honourable.” (Yes, the Oxford English Dictionary uses the Oxford comma.)

I asked Michael Wex, author of the bestselling book on Yiddish of all time, Born to Kvetch, how he defines it.

“If there were a Platonic ideal of what being a person is, the best possible person, that’s the mensch,” Wex said. “A standup person who does the right thing, not because they’re going to get something for it, not because it’s going to benefit them, but because it’s the right thing to do.”

He should know. Among Wex’s eight published books is How to be a Mentsh (& Not a Schmuck), which his website describes as “a self-help book from a Talmudic perspective.” When we spoke, he noted that the word was in broad enough mainstream usage by 1960 to make an appearance in The Apartment, a film starring Jack Lemmon, Shirley MacLaine and Billy Wilder that won five Academy Awards.

“So it’s been around for quite a while,” he said. “I think the average literate person, whether they’re Jewish or not, would be able to tell you what it means in a general sense — a good person.”

Though the Yiddish — and German — origins of “mensch” literally translate to “man,” Wex assured me the term is non-gendered. He likened it to (increasingly outdated) usage of words like “mankind” to mean humankind. There’s no parallel term for a woman, he said, because mensch is the parallel term; “You can talk about a woman and say she’s a mensch.”

Which, I suppose, brings us to the question of whether I would wear a T-shirt with the word mensch on it. Well, nobody’s ever given me one.