Naomi Wolf: Trapped by Her Own ‘Beauty Myth’

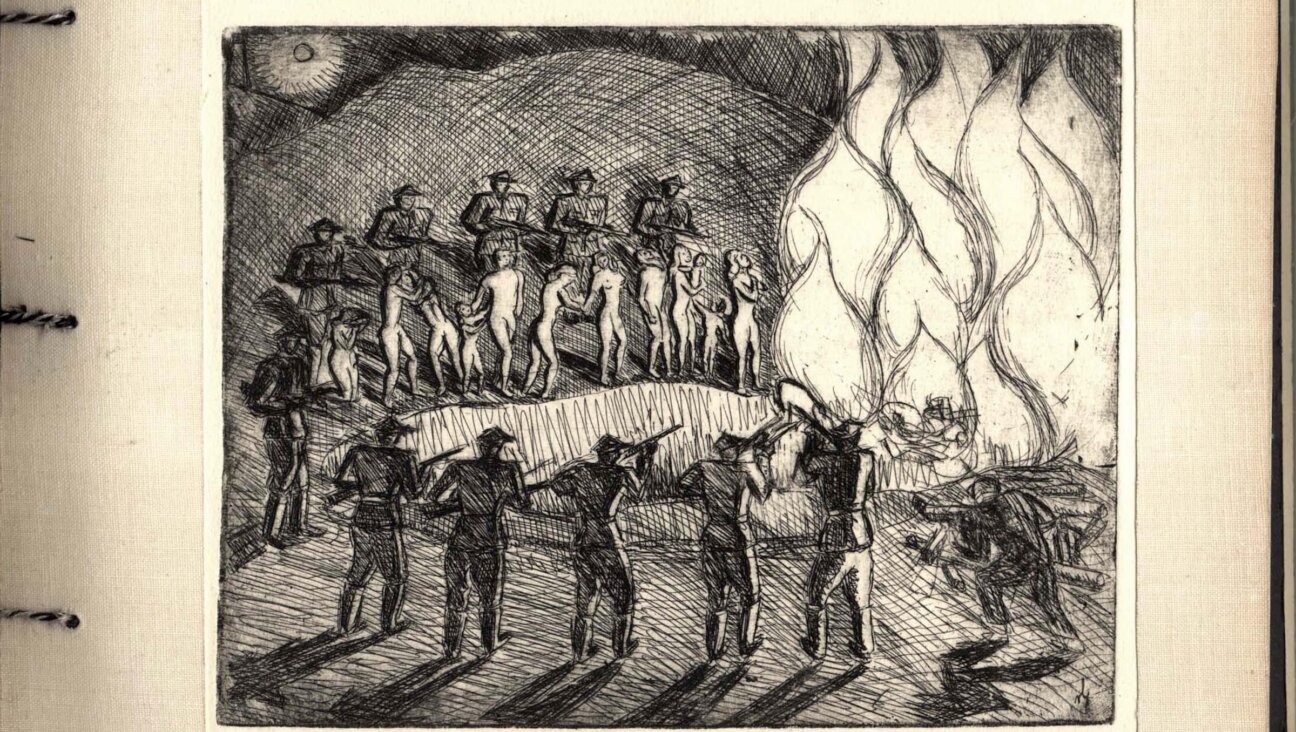

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Naomi Wolf is really getting on my nerves. It feels terrible to say that because she has made some key contributions to feminist consciousness over the years. Her first major book, “The Beauty Myth,” outlining the litany of damaging effects of the beauty industry on women and girls’ self-image is a classic that has indelibly impacted feminist thinking about body and commercialization of femininity. Her analysis of the female imagery of “The Angel in the House” offers some of the most useful insights in trying to understand women’s battles for self-expression and empowerment — especially religious women.

That said, I think she may really be losing it. I started to think this last year when she wrote a delusional essay glorifying the sexuality of repressed Muslim women who wear Victoria’s Secret under layers of hijab. She had some similar commentary about Orthodox women as well, which made her sound like some kind of cross between a rabbi preaching at a frat house and a repentant stripper. Cover up and you’ll find your spiritual salvation, was more or less her message at the time. She says all this, by the way, while wearing revealing clothes, globs of make-up, and Fran Drescher-worthy hair.

Her latest essay takes the cake. “A wrinkle in time: Twenty years after ‘The Beauty Myth,’ Naomi Wolf addresses The Aging Myth”, published recently the Washington Post, is a retrospective on her writing that comes across less as feminist scholarship and more like a ditsy celebration of the middle-age cocktail party.

She could have written an intriguing comparison of the beauty industry then and now, bolstered by the volumes of research that has been conducted since then about gender in industries such as advertising, Hollywood, fashion, and cosmetic surgery. Instead, she offered two thousand words mostly about her experiences sitting at a dinner party with middle aged men and their twenty-something blonde partners. Her conclusion from these experiences, by the way, is that all is well for the 40-plus woman.

“I personally expected that when I entered the middle of my life, I would start to mourn my youthful physical self,” she writes, “and that, even though I had thought long and hard about the dangers of the beauty myth, I would feel a sense of existential loss of self when my appearance began to change.” Why is that admission helpful? Why is she saying that despite all her work, she completely internalized the messages? This is so disempowering — that the more she studied these issues, the more she felt compelled to try and live up to the artificial standards of beauty.

She follows up with a sigh of relief. “Those pangs of loss have largely not happened,” she writes. “Not for me and not for the women I know and admire.” Her proof of how fabulous she feels as she approaches 50 is that all her friends can easily laugh at the young blond women next to the middle-age men at those parties. “Indeed, at events I have attended recently, cadres of conventionally beautiful young women seem now to be treated almost like wallpaper or like the catering staff,” she casually comments.

This is just astounding to me. She encounters a series of troubling phenomena related to her research —men continuing to abandon their wives in search of younger “models”, young women doing whatever it takes in order to receive the attention of older men, and middle aged women mocking younger women as “wallpaper” or “catering staff” — and her conclusion is that all is well?! Sure, the older women may in fact be “fine” or even “fabulous” in the face of all this. Therapy, diet pills, and large divorce settlements may help maintain that youthful glow that she admires. But all is not well. Women’s lives are at risk at every stage, younger and older, threatened by social mores that still consider blonde hair and thinness to be the be-all and end-all of women’s success.

Wolf admits it herself. Sure, she has one friend who boldly decided to keep her grey hair, but Wolf gets “startled” when she forgets her color rinse. She may have lots of friends who look better than they did in college, as she writes, but that only begs the issue. Despite all her research back then, she has become a caricature, looking at her friends based on how thin and sexy they are despite their age, and how much more charming they can be at dinner parties than 20-year olds.

I was expecting so much more. I was looking for a sharp, complex and intelligent analysis from an accomplished woman. But I guess even smart, accomplished women can be trapped by the beauty myth.