Should Hasidic Moms Have A Dress Code?

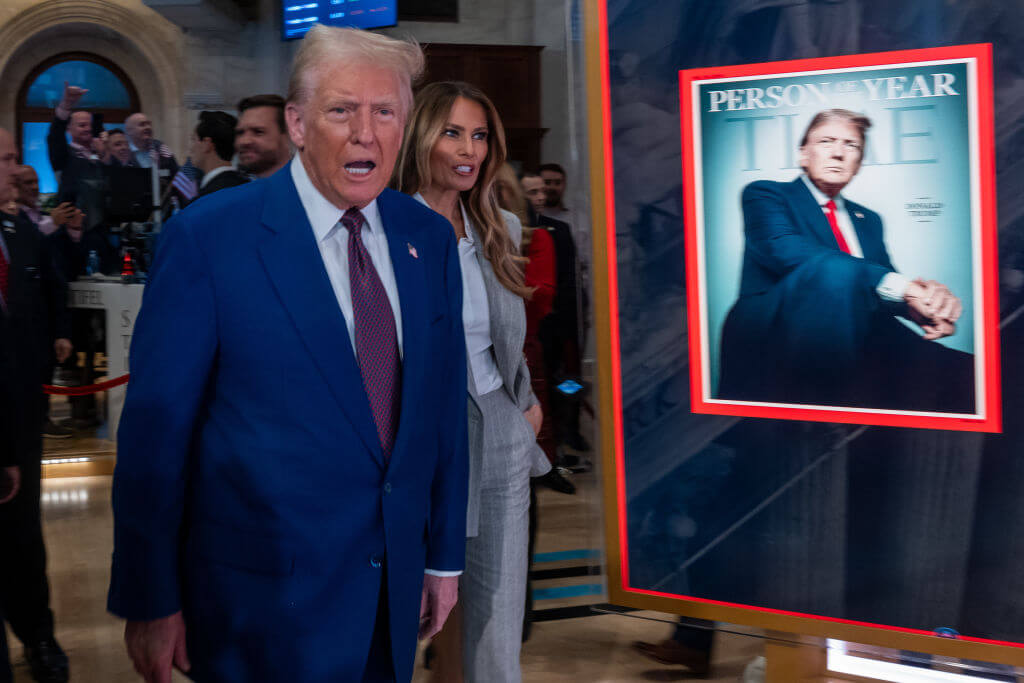

Women visiting the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Image by Getty Images

Who among us would disagree with the suggestion that we “unite to show our children that there is another way”? Out of context, this suggestion seems as if it might relate to climate change, say. Or just something like basic human decency.

Sam Kestenbaum reports that a Hasidic girls school in Crown Heights, Bnos Menachem, has implemented a new dress code for the mothers, via a letter offering platitudes about “our children” and “mak[ing] a significant difference.” (Details here.) The “another way” remark would seem to be about the alternative to a dystopia where women’s necklines make the occasional appearance.

The rules are, as one might expect, not about tube tops or miniskirts, but rather about the sorts of violations that would only make sense within a Hasidic context. “No denim” would seem to mean denim midi or maxi skirts, not cutoffs. (Only one item on the seven-point list is underlined: “Shaitel length should not exceed the shoulder blades.”) The list would appear to be about making sure already modestly-dressed women stay in line.

The letter does not explain where the mothers are forbidden from wearing denim, brightly colored nail polish, or longer-than-lob shaitels. The “community,” “neighborhood” and “home” are all referenced, suggesting a requirement extending beyond school pickup or functions.

In one sense, look, the school can do this. Bnos Menachem is part of a voluntary community, and anyone who wants to wear something really out there like glitter nail polish or open-toed shoes has the option of sending her daughter(s) to public school. I certainly don’t think it’s for the state to come in and nix the idea of a dress code for moms. And it’s not so odd the rules only apply to mothers, not fathers, given that it’s a girls school.

But is a dress code for mothers a good idea? I see a few potential pitfalls:

-It infantilizes the mothers, extending what are effectively dress code-type rules to adult women, telling them that the way they’re already dressing, in observance of their faith, isn’t good enough.

-It punishes the children for the parents’ actions. Actions apparently off school premises. (Imagine a kid getting expelled because her mother wore an elbow-revealing shirt to work, or sandals to do grocery shopping.) A girl herself might be excelling at the school, really making a go of it, but alas, her mother went with too iridescent a nail polish at the CVS, so never mind.

-It threatens to needlessly exclude families from the school and the community who support its values but, say, wore leggings rather than tights under their long skirts this one time and therefore offended whichever judge of modesty was assessing their calf-to-ankle situation. The stakes seem rather high; the violations minor veering into absurd.

I can see how, if the school – where parents chose to send their kids – is teaching the kids that there’s only one acceptable way to dress, it would be confusing if they were getting different messages at home and at school. But it seems as if there might be better ways to promote Jewish values than the micromanagement of grown women’s attire.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy edits the Sisterhood, and can be reached at [email protected]. She is the author of “The Perils Of ‘Privilege’”, from St. Martin’s Press. Follow her on Twitter, @tweetertation

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO