I Moved To Berlin — And Found My Jewish Identity

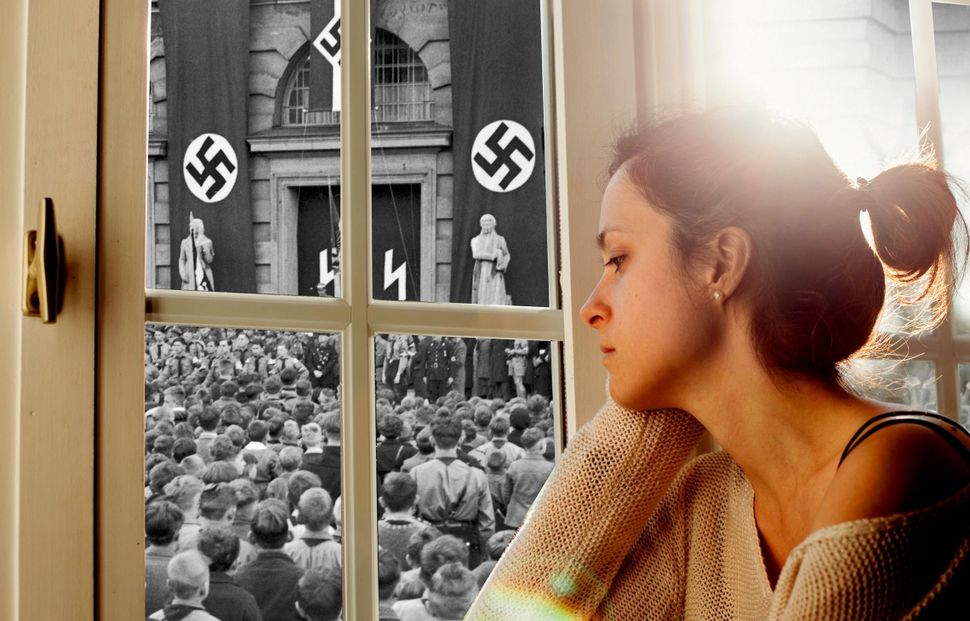

Image by Nikki Casey

I arrived in Berlin on the precipice of great change – as a newlywed, my new husband from a Turkish-German family.

My late Jewish grandmother, Selma Goldberg, had never wanted me to travel to, let alone live in, Germany.

“They’d do it again, given half a chance,” she warned me, safely tucked inside of her apartment on 58th street and 9th avenue, the belly of Hell’s Kitchen in New York City no longer a haven for artists but now millennials and new bistros.

Still, something had drawn me to the German language in college, how challenging and faraway it seemed, and how familiar to the intonations of the Yiddish sprinkled throughout my childhood. I traveled to Berlin many times in the decade between learning German and marrying my husband, Ufuk, in 2012, but only got to know the city intimately once we settled there.

I was unaware that the apartment Ufuk rented sat at the edge of Berlin’s former Jewish quarter when I moved in.

On my first days there, I explored past the beautiful fountain at Viktoria-Luise-Platz, smitten with the altbaus that remained, struck by the way that trees formed canopies over the streets, cafes filled with life spilled onto the sidewalks and summer days felt like they would never end. I still remember when I arrived on Munchenerstrasse and saw the first signs, remembrances of the Jews who had once lived in the area posted throughout the “Bavarian Quarter”, spelling out the regulations coming to dominate—and ultimately discard of—their lives. “Jews may not own or run shops or mail-order businesses. “Jews can no longer have pets.” “Occupational bans of Jewish actors.”

Struck with sudden grief, I looked away, down at the ground. But right below my feet, I saw a golden square, one of the many stolpersteine (stumbling stones) in Berlin commemorating individuals who perished in the Nazi era.

Everywhere and everything was marked with this history, the sky above, the ground below.

I bent down and touched the stone. “Here lived Herman Goldberger, born 1874, expelled in 1938 to Poland, murdered in 1942 in the Bochnia Ghetto.” I thought of my grandmother, Selma Goldberg, then and wondered if she had been right.

Having traveled the world, working in over a dozen countries, I had never imagined the way in which moving to Berlin would make me acutely aware of my own Jewishness. I became fixated on the ancestry and on the lives of individuals, such as Herman Goldberger and later a man named Eduard Salinger, commemorated by those single stones.

I felt I had to do something for them, and for them I learned my first full Jewish prayer: M’chal’kel cha-yim b-chesed. “You nourish life with compassion.” I whispered this when I stood at the stones, when I said their names. As Rabbi Heschel once explained, “Prayer begins at the edge of emptiness.” I was empty; I didn’t know what else to do.

My husband was a renowned tour guide of Jewish Berlin, and when he finally took me on a tour, I saw the whole city—and myself—through new eyes. We traveled south to the Grunewald Train Station, where the screeching sound of tires from the adjacent working subway melds with an abandoned platform from which Berlin’s Jews were once transported to their deaths. Piles of stones called caerns have been built by visitors, a tradition born in the desert where the buried dead are covered in stone piles to save their bodies from animals. Trees grow in the center of the train tracks, a sign of new life. The beauty of the surrounding area, of villas, lush remains of forestry, cafes bursting with revelry, is heartbreaking.

But for all that Berlin broke in me, it also bestowed upon me a deep pride in my own Jewish identity. Soon I realized, not all was lost. One morning, at Ludwigkircheplatz, we encountered a woman polishing stumbling stones outside of her apartment. Living in the same building where two Jewish Berliners once resided, she cared for their small memorials with the devotion and meticulousness of a grieving neighbor. She nourished their lost lives with compassion too.

And on Munchenerstrasse, where I first discovered the signs recollecting how, when and where Jews had been forbidden, a 6th grade class of children has built a wall out of bricks the color of burnt cardamom. On each a name: Else, Alfred. Their project is visible from the street, but hardly so, between a gate and thriving trees. The wall has at least 100 names inscribed upon it. These are not the names of the children, themselves, but the names of Jewish residents of the Bavarian District. Every year at this Locknitz elementary school, located in the exact place of a destroyed synagogue, 6th grade students each research a former Jewish resident from the district. They nourish those lost lives with compassion too.

My late grandmother warned me to never go to Germany, for fear of what I might find.

But what I found was a painful history that belonged to me as so many others, and a citizenry that keeps it alive with compassion.

Berlin made me aware that I had taken for granted where I came from and who I was, being raised in New York City where diversity reigned.

In its streets, its stumbling stones, its signs, Berlin showed me loss so great that I had to face myself. This city led me to a stronger sense of self — one I hadn’t known I was looking for.

Eiisabeth Becker is a cultural sociogist and writer, interested in religious, ethnic and racial diversity and inclusion. Her first memoir documenting her cross-cultural marriage, ‘On the Edge of the Worlds’, is represented by Jessica Craig Literary, and her ethnography ‘Unsettled Islam’ is under contract with University of Chicago Press.