Reading The Story Of Rebecca And Isaac In The Age Of Roy Moore

Image by Getty Images

According to our tradition, when Isaac and Rebecca met for the first time — in last week’s Torah portion — it was love at first sight. Rebecca, journeying back from her land with Abraham’s servant, sees Isaac from the distance and promptly falls off her camel. Rashi, the medieval French philosopher, says “she sees him majestic and was dumbfounded.” After they meet, Isaac brings her into his childhood home and marries her. “Isaac loved her,” which is the first time the Torah uses this word vis-a-vis a relationship of partners.

In the Midrash (Breshit Rabba 60:16), our rabbis embellish the romantic Torah text to show how full and beautiful their love was, describing how Rebecca physically and spiritually lights up Isaac’s world, which had grown dark since the death of his mother.

With the backdrop of this love story, this week’s Torah portion, Toldot, should come as a shock. Isaac, who had just received a blessing for himself and his offspring, finds himself in the land of Gerar and is asked by “the men of the place,” “Who is the woman?” Out of fear for his life, Isaac answers, “She is my sister.” How could a man who loves his wife put her in such danger and risk the possibility that she would be abused or raped by Abimelech or another Philistine leader? How do we reconcile the Isaac of love and devotion with the Isaac who jeopardizes the chastity and safety of his wife?

These questions arise year to year as we approach this text, yet they feel more salient, given what is happening right now in our world, with a new and greater awakening about the pervasiveness of male sexual abuse, especially, but not exclusively, toward women.

Yet, most of us do not engage these questions because we may, by habit or choice, prefer to gloss over the parts in our Torah that do not match our modern values or do not paint our ancestors in a positive light. We might privilege the story of Abraham arguing with God for Sodom or Gomorrah yet neglect to address the fact that this same Abraham is the very same man who passes off his wife to a strange and powerful ruler not once, but twice. We may study the love story of Isaac and Rebecca without naming the troubling behavior that undermines that narrative.

As spiritual leaders and educators, we believe we must reckon with the Torah in its entirety and struggle with the complex and problematic characters that make up our ancestry. Talmud Torah, in our understanding, is a process of lifting up the beautiful and ennobling and of wrestling with what’s painful, troubling and embarrassing. This is not just a hermeneutical position; we believe approaching Torah this way helps us to clarify our values and positions and teach our children what is right and what is wrong.

In that vein, and in light of the ongoing revelations of sexual misconduct, this week’s Torah portion offers an opportunity to reflect on the issue of accountability vis-a-vis misuse of power.

Isaac’s story, while troubling, is different from the two other “sister-wife” narratives that come before, in which his father, Abraham, passes off Sarah to foreign rulers. Looking at those differences, we may seek to excuse Isaac’s behavior or lessen its severity. After all, Isaac lacked positive role models for how to treat the women closest to him in his life. And when a situation arose that made him scared and uncomfortable, he simply did as his father did and sought to save himself by giving his wife over to the ruling authority. His response was Pavlovian — we could argue — learned behavior based on observations or stories from his family.

We might also seek to give Isaac “a pass” because he loved his wife so much that his passion for her was the very thing that stops something terrible from happening to her. The text says that Isaac was “playing” with Rebecca in the open — “playing,” from the same root word as Isaac’s very name, could be flirting, laughing, being physically affectionate. Either way, we see again that palpable spark we mentioned at the beginning. Because he loved his wife, it’s surely not as bad a situation, right?

And we might think to ourselves that Isaac’s behavior is less troubling because “all’s well that ends well.” In the end, Rebecca remains untainted and has no physical contact with those who otherwise might have violated her, whereas a p’shat, plain, reading of Abraham’s encounter with the Pharaoh is that Sarah has entered the foreign ruler’s harem and has suffered abuse.

Yet, while all these differences are true, Isaac’s behavior is nonetheless egregious and needs to be called out. A lack of role models is not an excuse to abuse power. The way a person feels about their victim does not change the fact of terrible choices. The fact that no one was harmed in this case does not mean that no one will be harmed in a future case. With the Torah and in life, we should not let anyone who mistreats or abuses escape accountability.

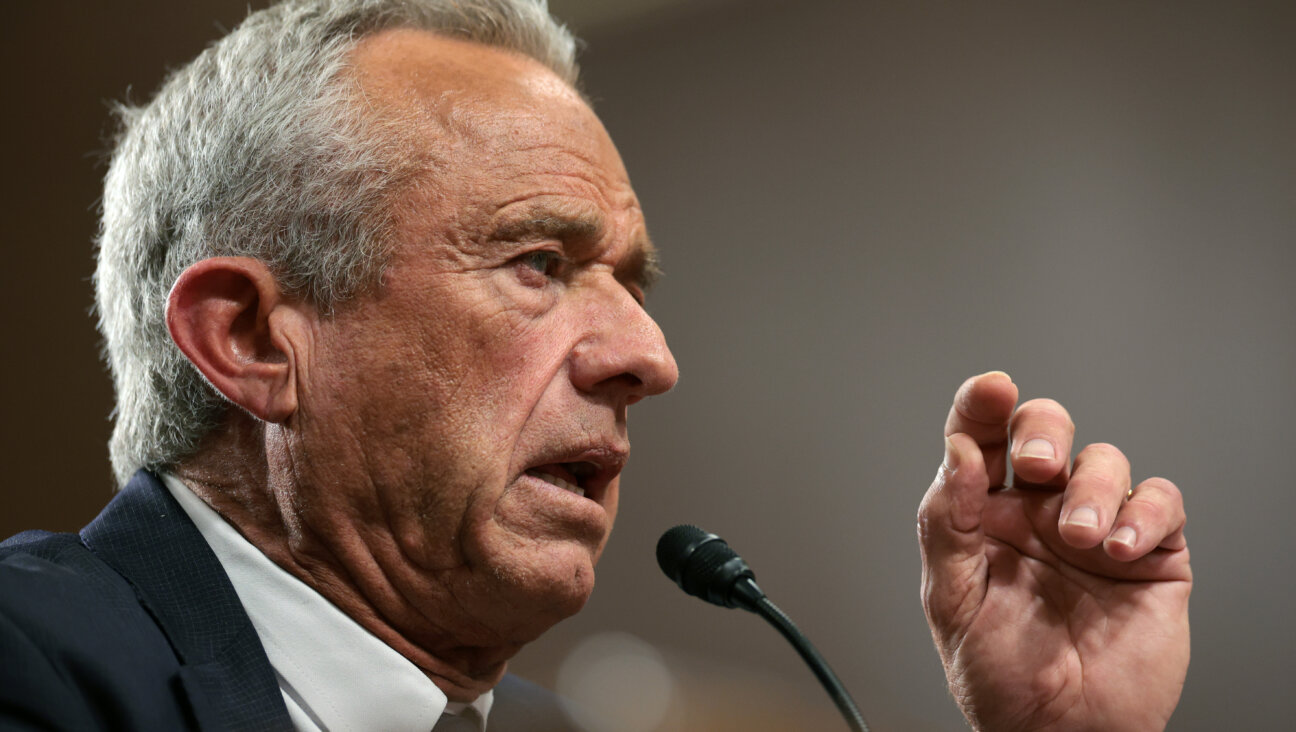

This week, we had a real-life example of this lesson, when we learned of the sexual abuse by a cultural icon whose reputation was built “making audiences laugh about hypocrisy — especially male hypocrisy” and who “boosted the careers of women, and is sometimes viewed as a feminist by fans and critics” (according to The New York Times). Louis C.K.’s actions prove that sexual misconduct can come from even those we believe are sympathetic to women and to equality, and that no one, no matter how revered, is immune to being called out for predatory and misogynist behavior.

Further, it is precisely when we allow an action to “slide” because we perceive the person who does it to be noble or well meaning, or because “it’s not that bad,” that we reinforce a dangerous paradigm that only the worst sexual abuse is worthy of attention. Calling out Isaac can help us teach ourselves and others about the continuum of sexual abuse that exists in our society, as it did in our biblical times.

Our goal is not to smash the ideal of Rebecca and Isaac’s love, but rather to smash the idols of rape culture in our own holy texts. Except in Midrash, idols don’t get smashed in a day. We have much work to do educating our sons (and our daughters) to change the culture of gender-based violence and assaults of all kind. We need to invite men to change their attitudes and behaviors and talk to and teach other men to do the same. We believe that as Jews we must start with our ancient sacred texts, to wrestle — in an age-appropriate way — with and problematize our texts and to call out behaviors that are incongruent with our deepest-held values.

Let us learn sacred lessons from this and other stories — ones that lead us to create the kind of world we want our children to inhabit.

Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Herrmann is the rabbi of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism. Tehilah Eisenstadt is the director of Education & Family Engagement at the Society of the Advancement of Judaism.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO