Kamm Affair Continues To Roil Israel

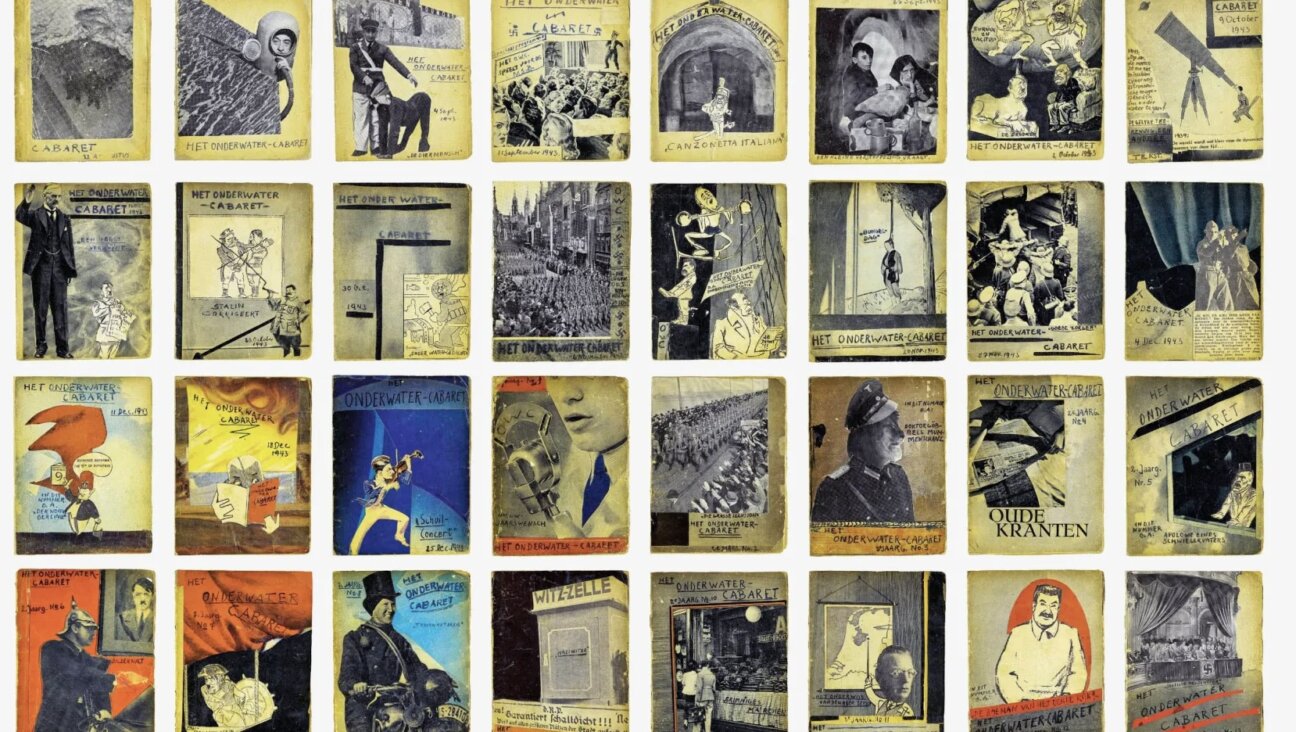

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In Israel, the most famous name charged with espionage for leaking classified information was nuclear technician Mordechai Vanunu, who spent 18 years in prison for providing a British newspaper with information and photos of the Israeli nuclear reactor in Dimona.

That is, until Anat Kamm.

The 23-year-old former Israel Defense Forces soldier, set to go on trial May 12, is accused of leaking about 2,000 classified military documents to Uri Blau, an investigative reporter for Haaretz. This complicated case has shed light on Israel’s inherent tension between maintaining its position as the Middle East’s leading democracy protecting the freedom of the press, and protecting secret military information for security considerations.

The case is expected to soon reach an important fork in the road, when Israeli prosecutors will decide how to deal with Blau, who has not been formally charged, and Kamm. Settling with the two could indicate an Israeli wish to put an end to the legal and political drama, while asking for prolonged prison terms would be seen as an attempt to use the Kamm-Blau affair as a deterrent against any future leaks from the military that could be either embarrassing or dangerous for the public.

In a legal procedure earlier this year, made public only recently, Kamm stated the reason that she copied hundreds of classified documents during her army service and later handed them over to Blau. “It was important for me to bring the IDF’s policy to public knowledge,” she said, describing actions of the Israeli military as “war crimes.” She contends that the IDF was targeting Palestinians in the West Bank for assassination, in violation of an Israeli Supreme Court order. A spokesman for the IDF said that these claims were inaccurate.

This accusation comes at a time when Israel is facing increased criticism worldwide over its use of excessive force against the Palestinians. Though the document leaks occurred before the start of the military campaign in Gaza in December 2008, the mention of war crimes and alleged illegal activities by the military has touched a raw nerve in Israeli society.

In his November 2008 story in Haaretz, based on the documents he obtained from Kamm, Blau reported that despite clear instructions from Israel’s Supreme Court to avoid targeted killing of Palestinian suspects if an arrest is possible, the IDF selectively issued orders to kill suspects without first attempting to apprehend them.

After being questioned on the source of the documents, Blau’s lawyers reached an agreement with Israel’s security agency, the Shin Bet, requiring him to return some of the classified documents he was holding in return for avoiding prosecution and not revealing his source. Later, investigators reached Kamm, and on January 14 they charged her with espionage. She continues to be held under house arrest.

Israeli authorities now claim that Blau did not hand over the bulk of documents he was holding, and therefore the agreement reached with his lawyers no longer holds. Blau is currently in London and said he will not return to Israel, fearing arrest upon arrival.

(The Forward, which publishes weekly in Israel in the Haaretz English Edition, is not involved in this case.)

The case has set off a debate over the limits of free press in Israel and how to balance an open society with the need to maintain military security. Israel does not have shield laws protecting reporters and their sources and has not enacted rules to provide legal immunity to whistleblowers.

Still, in the past, authorities usually avoided going after journalists for holding classified information. A rare case of questioning a reporter occurred in 1993 when Reuven Pedatzur revealed information on the poor performance of anti-missile systems, based on leaked air force documents. Pedatzur was questioned several times by Israeli police for alleged espionage because he held classified documents, but the prosecution decided to drop the case. One reason cited for this decision was the concern that charging a journalist with espionage would cross a red line in relations between the press and government.

A petition signed by Israeli journalists April 11 in support of Blau echoes the same concern. “Every reporter held a classified document at one time or another,” the petition read, arguing that prosecuting Blau would “create a dangerous precedent in terms of freedom of speech.”

For some in the United States, this debate may sound familiar.

In certain respects, it resembles the controversy surrounding the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971, when Daniel Ellsberg, at the time a Department of Defense employee, leaked a government report detailing decision-making during the Vietnam War to The New York Times and The Washington Post. Ellsberg was charged under the Espionage Act, but the case was dismissed for gross government misconduct.

The Kamm-Blau affair also hits close to home for two Jewish activists formerly with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee. Steve Rosen and Keith Weissman were charged in 2005 under the Espionage Act with receiving classified information from Pentagon analyst Larry Franklin and passing it on to Israeli diplomats, to their bosses at AIPAC and to the media.

“I have a lot of sympathy with her,” Weissman said of Kamm, “but she is facing a hard time.” He thought that Kamm was aware of the fact that she was breaking the law but believed she was doing the right thing from a moral standpoint, just like Franklin in the AIPAC case.

Rosen said that his own run-in with the law over dealing with classified documents taught him to “be a little skeptical when it comes to these kinds of prosecutions.” Still, Rosen stressed that he believes the government does have the right to guard its secrets and that a decision on whether a leak should lead to prosecution depends on its content. This approach was upheld by judge T.S. Ellis III, who presided over Rosen and Weissman’s trial. Ellis ruled that in order to prove their guilt, the government would have to demonstrate that using the leaked information could indeed harm American national security interests. The case was eventually dropped by the Department of Justice.

Charges against those who leak classified information to journalists rarely get to court in either Israel or the United States

According to Steven Aftergood, director of the project on government secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, only three such cases were prosecuted in the United States: One involved Navy analyst Samuel Morison, who was convicted in 1985 after providing satellite images to Jane’s Fighting Ships publication. The other two cases had an Israeli angle: the AIPAC case, and the case of Shamai Leibowitz, who admitted passing to a blogger secret documents that he obtained through his work as an FBI linguist.

“Obviously they are not the only ones who leaked,” Aftergood said. “There were tens of thousands of leaks in the media in recent decades, and they mostly went unpunished.”

Contact Nathan Guttman at [email protected]