‘A new moment’: BDS activists cheer Sally Rooney’s boycott as Jewish groups mostly mum

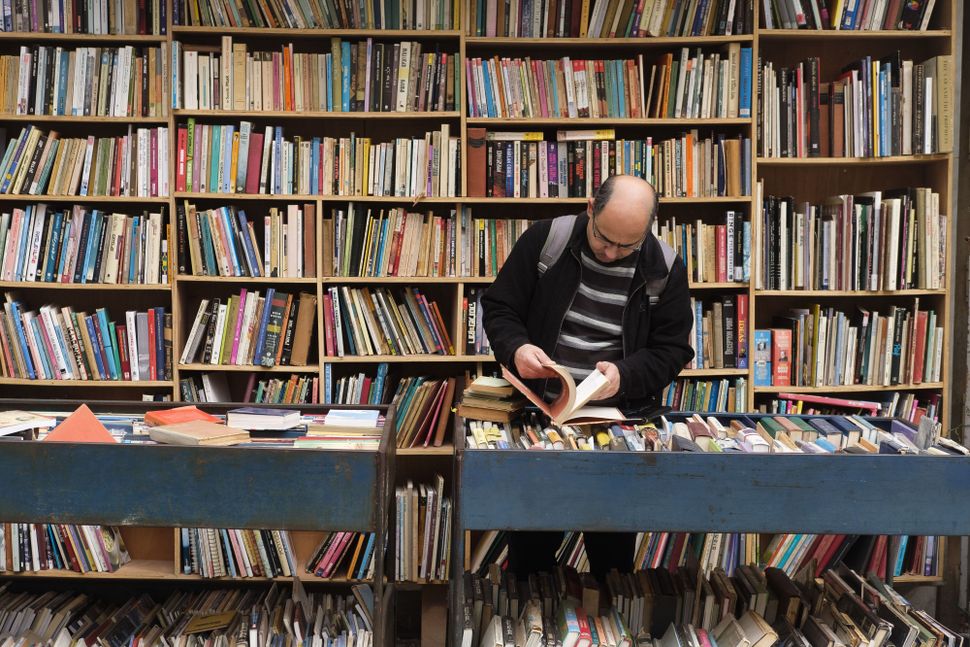

Photo by Getty Images

Sally Rooney’s announcement Tuesday that she refused to sell an Israeli publishing house the translation rights to her latest blockbuster novel marked the latest in a string of victories for Palestinians and their supporters calling for a boycott of Israel.

The news from the Irish literary star comes just months after Ben & Jerry’s decided that it would no longer sell ice cream in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. Both Rooney and Ben & Jerry’s said they made their decisions over Israel’s poor treatment of Palestinians. Rooney added that she did it in support of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, and cited an April report from Human Rights Watch that accused Israel of committing apartheid.

There are other signs that momentum is building for BDS. Burlington, Vt., last month nearly became the first American city to endorse the movement, and the campaign has also found fertile ground in U.S. teachers unions this year.

“We’re in a new moment,” said Ahmad Abuznaid, director of the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights.

Rooney, whose three novels have won acclaim for documenting the ennui of millennial women, is a Marxist who has previously expressed sympathy for the Palestinian cause. But her decision not to work with Modan, a top Israeli publisher who translated Rooney’s first two books, makes her perhaps the trendiest writer to back the Palestinian call for a boycott of Israel.

Changing attitudes?

Abuznaid said support has picked up for the general boycott of Israel that BDS calls for because the distinction between the Jewish state and its military occupation of the West Bank and blockade of Gaza has collapsed in recent years. To many, he suggested, the occupation that began after the 1967 war no longer seems temporary, making BDS more appealing to critics of Israeli human rights abuses.

Those critics include a small but powerful bloc of House Democrats who last month stripped additional funding for Israel’s Iron Dome missile defense system from a spending bill in Congress. Only two members of the progressive wing support BDS, and the funding was easily approved in a separate bill. But the delay startled those who expected Iron Dome funding to pass as quickly and easily as it has in the past.

Sally Rooney attends a photocall during the Edinburgh International Book Festival on August 22, 2017 in Edinburgh, Scotland By Simone Padovani/Awakening/Getty Images

Many of Israel’s supporters, including many mainstream Democrats who support a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, see BDS as a threat because its demands include recognizing the right of Palestinian refugees and their descendants to return to Israel, which could end its status as a Jewish-majority state.

Past authors’ support for BDS have not made as much of a splash as Rooney’s.

Alice Walker, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her novel The Color Purple, declined to allow an Israeli edition of the book in 2012. But Walker has come under fire for endorsing a slew of bizarre antisemitic conspiracy theories, which diminished the credibility of her boycott.

Other prominent authors who have supported BDS include Junot Diaz, who won the 2008 Pulitzer; Adrundhati Roy, the Indian novelist who won the Man Booker Prize in 1997; and the anticapitalist writer Naomi Klein. But it is unclear how their stances affected their work’s availability in Israel. An English version of at least one of Roy’s novels is sold by Steimatzky, a major Israeli bookstore chain, and Klein traveled to Israel in 2009 to promote a Hebrew translation of her book “Shock Doctrine.”

Boycotting Israel or boycotting Hebrew?

The full ramifications of Rooney’s boycott also remain unclear. Original reports of the author’s decision, in the Hebrew press in Israel and in an opinion column published Monday in the Forward, said she was refusing to have the novel translated into Hebrew.

On Tuesday morning, she issued a statement clarifying that she in fact just did not want the Hebrew rights to go to an Israeli publisher, saying she would allow the translation if it could be accomplished without violating the boycott. (The Forward updated the essay and added an editor’s note, while also publishing a separate article on Rooney’s statement.)

“I simply do not feel it would be right for me under the present circumstances to accept a new contract with an Israeli company that does not publicly distance itself from apartheid and support the U.N.-stipulated rights of the Palestinian people,” the statement said. “If I can find a way to sell these rights that is compliant with the BDS movement’s institutional boycott guidelines, I will be very pleased and proud to do so.”

Some prominent progressive Jews claimed on social media that the Forward had intentionally misrepresented Rooney’s position. Jodi Rudoren, the Forward’s editor-in-chief, called that suggestion “bizarre” and “distracting from the main issue.”

“Why would we do that? We have no horse in the fight,” she said in a text. “We originally published based on the information that was available, and when we got more information. We updated the column and built out our news report. That’s how journalism works.”

It is unclear whether there is a meaningful difference between boycotting Israeli publishers and refusing to have the book translated into Hebrew. In other words, there may be no way to have the book published in Hebrew while meeting Rooney’s and BDS’s criteria.

“In reality, there is no Hebrew publisher that can boycott Israel and remain in business, because almost all people who read books in Hebrew are located in Israel.” Roz Rothstein, chief of the pro-Israel group StandWithUs, said in an emailed statement. “In effect, this is discrimination on the basis of national origin and there is nothing just about it.”

Nancy Berg, co-editor of the anthology, “What We Talk about When We Talk about Hebrew (and What It Means to Americans),” said that the question of whether it is possible to sever modern Hebrew literature, including translations, from Hebrew’s status as the national language of Israel, is a complex one.

“While modern Hebrew is strongly identified with Israel, it existed before Israel, and continues to exist outside of Israel,” she noted. “So the short answer to your question is — in the best Jewish tradition — yes and no.”

Rooney’s defenders argue that it’s possible to boycott Israel without boycotting her Hebrew audience.

“She knows she has fans and readers that really appreciate her art and would appreciate having it in the Hebrew language,” said Abuznaid, the Palestinian rights activist. “The only thing we have to figure out is how we do that ethically along the lines of BDS.”

The boycott movement is represented by a central organization with very specific demands — including consumer boycotts of seven companies, for example. But individuals and organizations that choose to boycott Israel do so using myriad standards.

The Palestinian BDS National Committee deferred questions on how Rooney might pursue a Hebrew translation of “Beautiful World” while complying with the spirit of the boycott to the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, which did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The campaign specifically calls for a boycott of Israeli cultural institutions that are “complicit in maintaining the Israeli occupation and denial of basic Palestinian rights,” but does not specify the standards by which an institution — like a publishing house — would be considered complicit.

Rooney’s agent did not respond Tuesday to questions about whether her book, “Beautiful World, Where Are You?,” will be available to Israelis in English or whether a foreign publisher could translate the book into Hebrew and distribute it in Israel.

Her last book, “Normal People,” was translated into Hebrew and more than 20 other languages including Chinese, Russian and Persian, and was adapted into a television series for Hulu. “Beautiful World” was released on Sept. 7 and so far it appears to have been translated into German and Spanish.

A lack of outrage

The reaction to Rooney’s decision not to work with Modan, the Israeli publisher, prompted a more muted reaction from the Jewish establishment and pro-Israel advocates than Ben & Jerry’s decision earlier this summer. While the ice cream wars created a flurry of news releases, few groups responded to Rooney without first being asked.

Jonathan Greenblatt, chief executive of the Anti Defamation League, was one of the few to speak out, saying on Twitter Monday that Rooney was “embracing BDS’s hateful tactics.” An ADL spokesman doubled down, saying on Tuesday that Rooney’s move was “particularly unfortunate coming from an author committed to delving into interpersonal human relations.”

The American Jewish Committee did not respond to a request for comment and the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, which assailed Ben & Jerry’s over the summer, did not issue a statement.

But William Daroff, head of the conference, was unsparing when reached for comment.

“Ms. Rooney has blindly adopted the radical agenda of the BDS movement, which is dedicated to the elimination of the world’s only Jewish state,” Daroff said. “While happily accepting royalties from book sales in Iran, a promoter of global terror and a serial human rights abuser, she demonstrates a selectivity of principles that smacks of ignorance and antisemitism.”

Part of the reason more pro-Israel groups may not have spoken up earlier is because Rooney’s fame is not universal. While her books have enjoyed a degree of commercial success rare for literary fiction, and The New York Times reported on how promotional merchandise for the book’s release became a status symbol in certain circles, she is not particularly well known among the opponents of BDS.

“My guess is that most of the people who were scandalized by the Sally Rooney story 1) had to look up who Sally Rooney is and 2) wouldn’t have been able to read her work in Hebrew even if she published in it!” Yehuda Kurtzer, director of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America, said in an email. “So it is a less useful case both to advance the cause of BDS as a divisive force, and less urgent to respond to.”