Nazi collaborator monuments in Italy

Rudolfo Graziani, known as the Butcher of Fezzan and the Butcher of Ethiopia, has a children’s park named after him

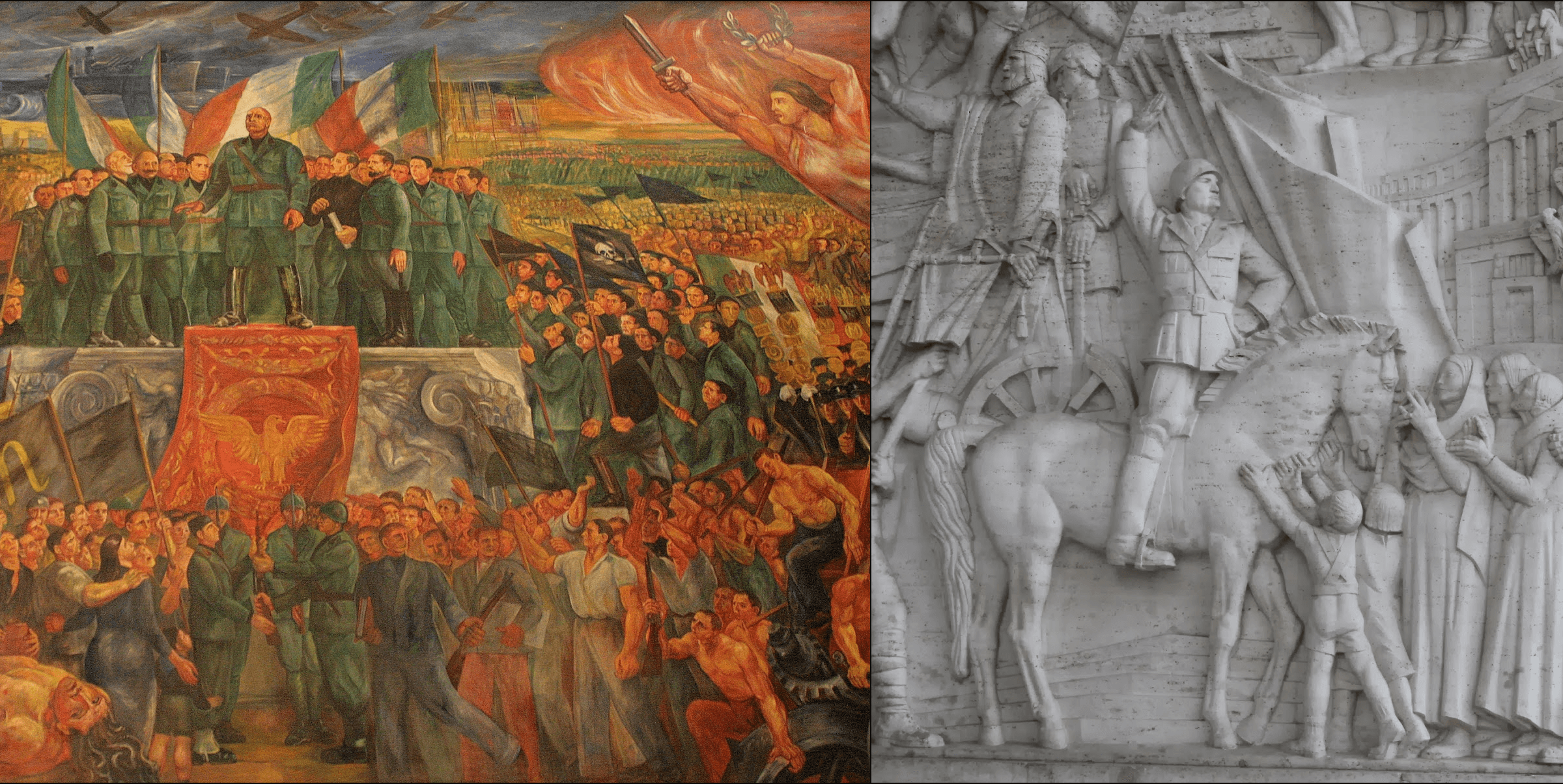

Left: detail of “The Apotheosis of Fascism” fresco at the Palazzo H headquarters of the Italian National Olympic Committee, Rome (Nick Carter). Right: detail of “A History of Rome Through Its Public Works” bas-relief on the Palazzo degli Uffici, Rome (So Much More to See/somuchmoretosee.com). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Note: due to the overwhelming number of streets, schools and hospitals honoring Victor Emmanuel III, this section is only a partial listing.

Rome — In 1942, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels wrote a frustrated diary entry about Italy’s “extremely lax” treatment of Jews: even though fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) was a Hitler ally who enacted antisemitic laws, everyday Italians resisted deporting their country’s Jews to the Nazi killing machine. This changed in 1943, when Mussolini was deposed and Italy surrendered to the Allies. Germany responded by invading the northern half of Italy and making Mussolini head of the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a Nazi puppet state. Over 7,800 Italian Jews trapped in RSI territory were imprisoned, deported and murdered.

Unlike nearly all other monuments in this project, Italy’s statues and murals glorifying Mussolini were created during his reign, not afterward. In other words, they’re not attempts to retroactively whitewash collaborators, but rather products of the totalitarian era in which they were made.

Rome’s remnants from the cult of Mussolini include an obelisk with “Mussolini DVX” (DVX is the Latin spelling of dux, or “leader” in Latin; Mussolini, who styled himself Il Duce or “The Leader” in Italian, used dvx to draw parallels between himself and ancient Rome). The obelisk is part of an athletic complex built by Mussolini – the project played into fascism’s worship of the male physique while evoking Roman emperors who glorified themselves by erecting forums and obelisks. The avenue leading from the obelisk to the stadiums features blocks with bas-reliefs of Mussolini’s achievements and is paved with mosaics with M for Mussolini, Dvce (stylized spelling of duce that harkens to ancient Rome), Dvce a Noi (“Duce, To Us,” which was a fascist slogan) and Dvce La Nostra Giovinezza a Voi Dedichiamo (“Duce, We Dedicate Our Youthful Lives to You”).

Mussolini is also in the colossal “The Apotheosis of Fascism” fresco in the headquarters of the Italian National Olympic Committee (bottom left); the even larger “Italy Among the Arts and Sciences” mural that dominates a lecture hall in Sapienza University of Rome’s Palazzo del Rettorato; the “Mussolini” fresco in the Casa Madre dei Mutilati di Guerra; and the massive “A History of Rome Through its Public Works” bas-relief on the Palazzo degli Uffici (bottom right).

See coverage in the New Yorker, Art & Object, Daily Beast and DW, phenomenal essay in SmartHistory and AP photo slideshow in Taiwan News.

***

Monte Giano and Villa Santa Maria — On the slopes of central Italy’s Monte Giano is a giant tribute to Mussolini: the letters DVX formed by a forest of 20,000 fir trees, above left. Planted in 1939 by forestry school cadets, the letters are big enough to be seen in Rome.

There’s also a smaller DUX etched onto a cliff overlooking the village of Villa Santa Maria, above right. See coverage in Politico Europe, Condé Nast Traveler, The Conversation, la Repubblika (Google translation here) and TG8.

Bolzano — One of the most unique examples of dealing with problematic monuments can be found on the ex-fascist party headquarters in the northern Italian city of Bolzano. The rectangular building features “The Triumph of Fascism,” a massive bas-relief centered on a figure of Mussolini on horseback and the fascist slogan “Credere, Obbedire, Combattere” (“Believe, Obey, Fight”).

In 2011, the city held a competition for ideas to contextualize the monument. The winning bid, installed in 2017, was to superimpose “Nobody Has the Right to Obey,” a quote by philosopher Hannah Arendt, onto the bas-relief. Arendt was a scholar of totalitarianism as well as a Holocaust survivor. Her quote, composed of illuminated letters, is written in Italian, German and Ladin (language spoken in northern Italy).

See project site with explanation of bas-relief and coverage in the Guardian and Italics Magazine.

Filettino and two other locales — This small mountain village has a children’s park honoring hometown mass murderer Rodolfo Graziani (1882–1955) aka the Butcher of Fezzan and the Butcher of Ethiopia. A marshal in Mussolini’s army, Graziani began committing war crimes before WWII broke out: between 1930 and 1934 he brutally suppressed a rebellion in the Italian colony of Libya using concentration camps and poison gas. The next year, Graziani was a commander in the Italian invasion of Ethiopia; after being targeted by an assassination attempt, he ordered the systematic massacre of 19,000–30,000 civilians. During WWII, Graziani was defense minister for the Italian Social Republic (RSI) Nazi puppet regime.

Graziani was sentenced to 19 years for collaborating with the Nazis; he was out in four months. Such a short prison stay is par for the course for even the most egregious collaborators (see the Germany section). He also has streets in the villages of Depressa and Neviano.

See coverage in la Repubblica (Google translation here), FrosinoneToday (Google translation here), JTA, the New York Times, BBC and Amsterdam News; coverage of Italian whitewashers turning perpetrators into victims in the Guardian and the Jerusalem Post; and an exploration of Italian neo-fascism and the Holocaust by the Centro Primo Levi. For a documentary about what Graziani did to Ethiopia see “If Only I Were That Warrior”.

Noicattaro and five other locales — A street and school celebrating endocrinologist Nicola Pende (1880–1970). In the summer of 1938, Pende and nine other prominent Italian scientists published “The Manifesto of Race,” a racist and antisemitic proclamation averring Italians were Aryans, Jews weren’t Italian and the purity of Italians must be vigorously defended. The manifesto, with its air of scientific “justification” for racism, laid the groundwork for Italy’s race laws enacted that fall. The laws, which stripped Jews of rights were a key step on the road to genocide.

Pende also has streets in Bari, Cassano delle Murge, Formigine, Modugno and Triggiano. Above right, antisemitic graffiti on a Trieste synagogue, December 1938. See the Los Angeles Review of Books on fascist scientists and the Jerusalem Post and The Local on Rome getting rid of two streets for authors of the “Manifesto of Race.”

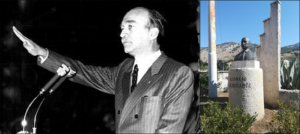

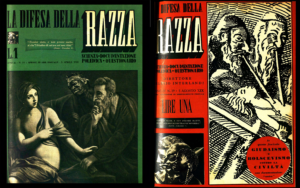

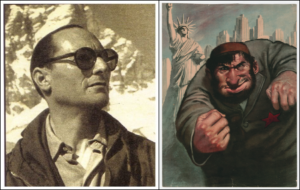

Affile and 80 other locations — A bust of Giorgio Almirante (1914–1988), member of the editorial board of the abhorrently racist and antisemitic La Difesa Della Raza (“The Defense of the Race”) magazine which published the “Manifesto of Race” (see Nicola Pende entry above). Typical covers during Almirante’s tenure include a lecherous Jew and Black man accosting a white woman (1939, below left) and Jews sucking blood from Italy (1941, below right).

In 1943, Almirante became cabinet head in the ministry of popular culture, RSI’s propaganda wing. Within two years of the war ending, he cofounded the Italian Social Movement, the successor to Mussolini’s party which ensured the proliferation of Italian neo-fascism.

Almirante also has a monument in Sacrofano; a park in Putignano; squares in Pofi and Vico del Gargano; and streets in Acquaviva delle Fonti, Aidone, Altamura, Andreotta, Anoia, Aversa, Bari, Botrugno, Canalicchio, Capaci, Carini, Carpino, Casarano, Castellammare del Golfo, Castelvetrano, Chiusa Sclafani, Crispiano, Curti, Fabrica di Roma, Fiumicino, Foggia, Frattari, Frignano, Galatina, Gatalone, Giarre, Ginosa, Guagnano, Ladispoli, L’Aquila, Lecce, Locorotondo, Marano Marchesato, Minturno, Mirto, Molfeta, Montecorvino Rovella, Montesilvano, Morlupo, Mottola, Noventa Vicentina, Pagani, Palmariggi, Pescantina, Pomezia, Praia a Mare, Racale, Ragusa, Ravanusa, Rieti, Rossano, San Carlo-Condofuri Marina, San Marco in Lamis, San Pietro a Maida, San Severo, Santa Caterina Villarmosa, Santa Maria, Santa Maria Capua Vetere, San Vito dei Normanni, Scalea, Sogliano Cavour, Sternatia, Surbo, Sutri, Taviano, Terlizzi, Torre Santa Susanna, Tortora Marina, Trani, Valenzano, Vasanello, Veglie, Vigasio, Viterbo, Usini and Zungri.

***

Rome — A street named for Gaetano Azzariti (1881–1961), lawyer who supported the 1938 race laws. Azzariti was president of the Tribunal of Race, a governmental commission which helped implement the laws. After the war, he became minister of justice and later chaired Italy’s supreme court. In 2015, Azzariti’s bust was quietly removed from the supreme court building, but his street remains.

Rome — A street named for Paolo Orano (1875–1945), fascist ideologue whose 1937 The Jews in Italy whipped up anti-Jewish sentiment on the eve of the passage of the 1938 race laws. Above right, the laws announced in Corriere della Sera, November 1938.

Sanremo, Reggio Calabria and numerous other locales — Sanremo has a bust of Victor Emmanuel III (1869–1947), Italian king who presided over Mussolini’s rise and signed the 1938 race laws. The king did little to resist Mussolini, only turning himself against the dictator and to the Allies when it was clear Italy had lost the war. Victor Emmanuel III himself was ousted from power in 1946 when Italy became a republic.

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2021, Victor Emmanuel III’s descendant wrote an apology to Italy’s Jewish community for his ancestor’s complicity in the persecution of Italian Jews. Several representatives of Italian Jewish organizations rejected the apology, citing the family’s decades of silence and refusal to take responsibility.

In addition to the bust in Sanremo (above right), monument in Reggio Calabria (below left), and fresco at the Casa Madre dei Mutilati di Guerra in Rome, Italy has an astounding number of streets, schools and hospitals honoring the king. An OpenStreetMap project from 2017–2018 located 388 toponyms, which is beyond the scope of this project (Google translation here).

It’s important to note that the Reggio Calabria monument, the Rome fresco and most likely many other Victor Emmanuel III tributes were created during his reign, not afterward (this is similar to the case of Mussolini tributes in the entries above). They’re not attempts to retroactively whitewash collaborators, but are instead products of the era in which they were made. Below right, Victor Emmanuel III inspecting troops, 1911.

***

Bari — A street for Gino Boccasile (1901–1952), hometown artist who created propaganda in Mussolini’s Italy and the RSI. Boccasile also illustrated propaganda materials for the 29th Waffen Grenadier Regiment of the SS (1st Italian), an Italian unit in the Waffen-SS. Above right, his poster of a Bolshevik Jew (a common antisemitic trope) in America.

Rome — The façade of the Santi Sergio e Bacco church features a statue of Iosif Slipyi (1892–1984), Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. In 1941, Slipyi welcomed the Nazis invading Ukraine; above left, Slipyi (third from right) about to greet Hans Frank, the Governor-General of Poland. Frank was hanged for crimes against humanity in Nuremberg.

In 1943, Slipyi once again assisted the Nazis by playing a crucial role in the creation of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS aka SS Galichina, a Ukrainian division in the Waffen-SS. He assigned chaplains to serve in the unit and personally celebrated mass at SS Galichina’s creation. The division went on to commit war crimes such as the Huta Pieniacka massacre when an SS Galichina subunit burned 500–1,000 Polish villagers alive.

In 1983, forty years after the Holocaust, Slipyi celebrated SS Galichina’s founding with gushing praise. “Let the memory of Ukrainian Galichian Division live with us forever as a testament to nations that we strive for freedom, statehood and are prepared for the greatest sacrifices for truth, fairness and peace to be in our land,” he proclaimed, calling on the faithful to pray for SS soldiers.

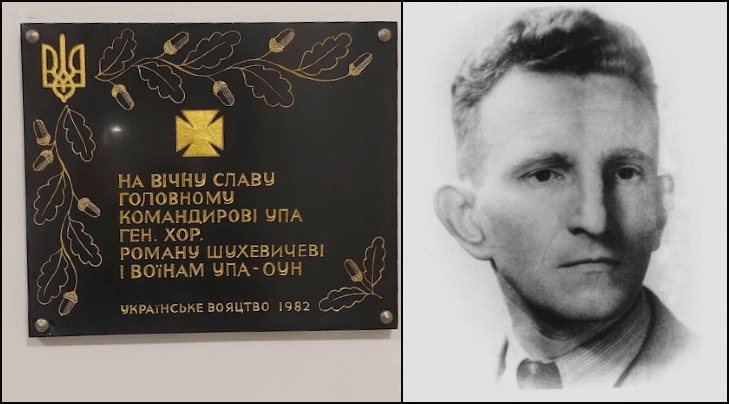

Slipyi is also prominently featured in an icon in Rome’s Santa Sofia a Via Boccea. That church also contains a memorial plaque honoring Roman Shukhevych (1907–1950), the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). Shukhevych, below right, was a leader in a Third Reich auxiliary police battalion as well as the OUN, a fascist group that had allied itself with the Nazis and participated in the Holocaust. Beginning in 1943 he commanded the UPA, the OUN’s paramilitary wing that massacred thousands of Jews and 70,000-100,000 Poles. The plaque, below left, was erected by an organization of Ukrainian veterans based in Britain; many of these were SS Galichina soldiers who were allowed to resettle in Britain.

See the JTA on Nazi symbols that are a regular part of SS Galichina commemorations. See the Canada, Ukraine and U.S. sections for more Slipyi glorification.

(Note: The Shukhevych, OUN and UPA plaque was added August 2023.)