50 years after making it to the baseball Hall of Fame, here’s how Sandy Koufax did it

The Brooklyn southpaw who famously skipped a World Series game on Yom Kippur may have been the greatest Jewish athlete ever

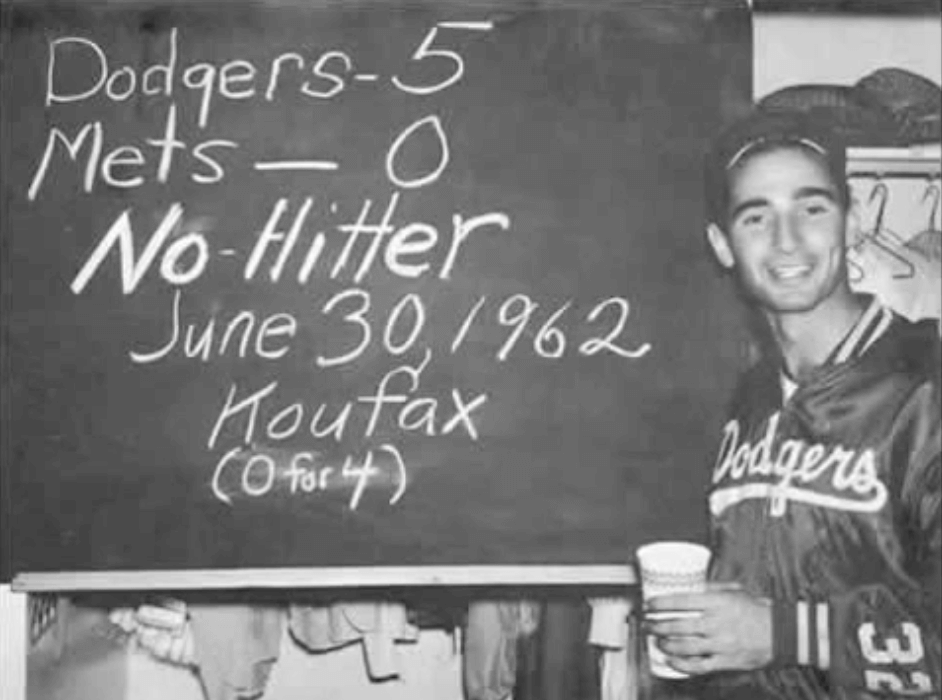

Sandy Koufax in front of a chalkboard summary of his first no-hitter on June 30, 1962. Photo by YouTube screenshot

Pitcher Sandy Koufax was the epitome of a late bloomer, not hitting his peak until his seventh season. But when it came to the baseball Hall of Fame, he was a man in a hurry.

On Aug. 7, 1972 – a half-century ago – the 36-year-old Koufax became the youngest player ever inducted, following perhaps the greatest period of dominance of any pitcher. Players must be retired for at least five years to be eligible for the baseball Hall of Fame, so Koufax’s decision to quit the sport at the age of 31 due to chronic arthritis in this throwing arm was a factor. But his selection in his first year was notable, a feat not accomplished by many of the sport’s transcendent players, such as Joe DiMaggio.

Youngest player to be inducted

Koufax received nearly 87% of the vote of the Baseball Writers Association of America, easily meeting the 75% required threshold. After the January 1972 vote, he downplayed entering the hall as the youngest player.

“Well, that’s only because I had to retire at 31,” Koufax said. “I had six good years, the last four being the best.” He added that he was surprised he got so many votes: “I didn’t have as many good years as many people who are in the Hall of Fame.”

At his induction speech seven months later in Cooperstown, New York, he remained self-effacing.

“Mine was a career that began ingloriously,” Koufax said, thanking Dodgers pitching coach Joe Becker, who “pushed me, shoved me, embarrassed me and made me work, and thank God for him.”

He added: “I thought after my first six years in baseball, it was going to be, ‘Go out and look for another job.’”

Greatest Jewish athlete ever?

Indeed, before Koufax became arguably the greatest Jewish athlete of all time, he was an out-of-control pitcher. Signed by his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers after pitching for one season at the University of Cincinnati, the southpaw piled up walks and wild pitches, and had a mostly mediocre first half-dozen seasons.

“When he first came up, he couldn’t throw a ball inside the batting cage,” quipped teammate Duke Snider.

After the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, the change of scenery didn’t initially do Koufax any good – he was 11-11 with a 4.48 ERA and led the National League with 17 wild pitches in their first season there, 1958.

By Koufax’s reckoning, things started to turn around when he decided not to throw to spots rather than try to blow the ball past every batter – which is when he said he became a pitcher, not just a thrower. The suggestion in 1961 by his Jewish catcher, Norm Sherry, that Koufax take something off his fastball, is credited with helping the pitcher reach his potential.

His first good season

His first good season was 1961, when the 25-year-old went 18-13 with a 3.52 ERA, setting a new National League record with 269 strikeouts. The next year, 1962, he threw the first of his four no-hitters, went 14-7 and posted a league-best 2.54 ERA.

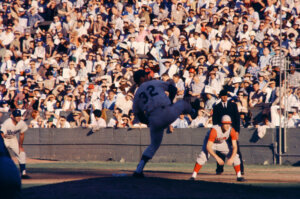

By 1963, he was virtually unhittable, leading the league in wins (25), ERA (1.88), shutouts (11) and strikeouts (306), winning both the Cy Young and MVP Awards.

“I can see how he won 25 games,” said New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra, one of seven other players inducted that cloudy summer day in 1972. “What I don’t understand is how he lost five.”

Over his last five seasons, Koufax led the league in ERA every time, while winning three Cy Young Awards and one MVP. He helped the Dodgers win three NL pennants and two World Series titles during that run.

In the ’63 World Series, he led the team to a sweep of the Yankees, the franchise that had bedeviled the Dodgers in multiple October subway series back when the team was in Brooklyn. Koufax went 2-0 with a 1.50 ERA, beating Yankees ace Whitey Ford in the first and final games, to claim the series MVP.

Skipping a World Series game

The Dodgers returned to the World Series in 1965, when Koufax became an even bigger hero to many Jewish fans by sitting out the first game because it fell on Yom Kippur. That didn’t slow him down on the field – he went 2-1 against the Minnesota Twins, and threw a three-hit, complete game shutout in the seventh and deciding game, winning the World Series MVP again, this time with a 0.38 ERA.

The next year, Koufax went out on top – going 27-9 with a 1.73 ERA and 27 complete games in his final season, 1966.

His combination of a devastating curveball and high-octane fastball left many hitters baffled in the early and mid ‘60s.

“Either he throws the fastest ball I’ve ever seen, or I’m going blind,” said outfielder Richie Ashburn, a two-time batting champion and lifetime .308 hitter.

The ‘Melting Pot’ inductees

Koufax’s co-inductees in ’72 included catcher Josh Gibson and first baseman Buck Leonard, the first Hall of Fame selections to have played their entire careers in the Negro Leagues. Koufax, Leonard, Berra, and pitchers Early Wynn and Lefty Gomez were inducted that day, along with three others posthumously, including Gibson.

“They scarcely could have been more representative of Melting Pot USA,” The Sporting News wrote of the five living inductees. “Humble and appreciative, they stood before a microphone in typically small-town USA … A Jew from New York, an Italian from Missouri, a Scotch-Irish-Indian from Alabama, a Spaniard from California and a Negro from North Carolina.”

Ever humble, Koufax said, “How good it feels to be in such distinguished company.”