This doctor steered Hawaii through the worst of the pandemic. Now he wants to be governor

Josh Green faced down antisemites and vaccine protesters — while working weekends in an ER and keeping the public informed about COVID-19 caseloads

Dr. Josh Green is running for governor of Hawaii. Courtesy of Josh Green

UPDATE: Josh Green won Hawaii’s Democratic gubernatorial primary on Aug. 13. Read about what inspired him to run for office and the challenges he’s faced getting to this point in this profile.

HONOLULU — The protesters stretched around the block every night in the summer of 2021, blocking traffic and blasting air horns. They surrounded Josh Green’s condo building and aimed strobe lights into his neighbors’ windows. Inside, his wife and children listened as the protests against COVID-19 vaccines and masks grew ugly, with demonstrators screaming antisemitic slurs, death threats and rants about globalization.

For weeks, Green had been pulling down signs plastered all over his neighborhood, the ones with his picture that read “Jew” and “Fraud,” and handed them over to the state attorney general. Then one day, someone stopped him on a Waikiki sidewalk.

“All you kikes are going to have to be killed,” the man said.

Green stood in disbelief. “I hadn’t heard that word in a decade,” said Green, 52, who is Hawaii’s lieutenant governor as well as a medical doctor on the frontlines of the pandemic. “But it was a reflection of this guy’s rage at me for being both a doctor and a proponent of being vaccinated, and also my Judaism.”

As vile as the stranger’s remark was, Green realized that the protesters were acting out of fear. To help combat that fear, Green decided to run for governor.

A ‘good doctor’ changed his life

Joshua Green grew up in Pittsburgh surrounded by a large Jewish community. As a toddler, his parents noticed that he lagged behind his peers and wasn’t making developmental milestones. They wondered if he had an intellectual disability. Instead, when Green was 2, a doctor discovered congenital issues with his eustachian tubes. Green was deaf. Two surgeries later, his hearing was restored.

Green says he was lucky to have a “good doctor, good parents, a good community and a good synagogue. … I almost didn’t make it because I couldn’t hear. So I always reflect on that.”

Green has also seen how medical care can change people’s minds when it comes to COVID-19. During one of the August 2021 protests, Green told Chris Wikoff, a leader of the Hawaii Freedom Coalition anti-vaccination group, “You’re gonna catch coronavirus, and I’ll take care of you in the ER. You should rethink this.” And that’s exactly how it played out. Wikoff and his wife both contracted COVID-19. Wikoff was hospitalized, and the life-threatening experience caused Wikoff to abandon the coalition and disavow the movement.

From Africa to rural Hawaii

Green graduated from medical school at Pennsylvania State University in three years instead of the usual four. He used the fourth year for a mission to Swaziland. He notes that Jews “as a culture … are not missionaries.” But this mission was about providing medical care, not proselytizing religion.

His first lesson in Swaziland was about corruption: The medication and equipment his team brought was confiscated by the military. His second lesson was about handling disease outbreaks. Over 50% of his patients were HIV-positive; many others had malaria. “Half the hospital was a hospital, and the other half became an orphanage because children lost their parents,” he said.

Returning to the U.S., Green applied to the National Health Corps and was assigned to serve four years in Ka’u on the Big Island, a rural area stretching over 900 square miles, including a large portion of Volcanoes National Park and the world-famous black sand beach, Punaluu. The posting immersed him in Hawaii’s struggling rural healthcare system, caring for over 8,000 Filipino and Hawaiian patients. Many lacked access to specialty care, drug treatment, rehab or mental health care. (The current wait for a bed in a mental health facility in Hawaii is six to eight weeks.)

In 2004, he decided that making a difference in the medical field wasn’t enough. So he ran for a seat in the Hawaii House of Representatives, the lower house of the state legislature. Green put on his scrubs and went door to door, speaking directly with residents about their issues.

He won the election and served two terms before being elected to the state Senate in 2008. He served until 2018, when, after winning the Democratic Lieutenant Governor primary, he teamed up with the incumbent governor, David Ige, who was up for re-election. They won handily, garnering 62% of the vote, the highest of any gubernatorial race in state history.

A different epidemic

Six weeks before the coronavirus pandemic began, Green helped stem another deadly epidemic. In 2019, two Samoan children had died from incorrectly prepared measles vaccines, and many Samoans became suspicious of the vaccine. Declining vaccination rates created the perfect conditions for the virus to take hold. At one point, so many babies died that funeral homes ran out of tiny coffins.

On Dec. 2, 2019, Green was planning a measles vaccination mission to Samoa with a few friends when the Samoan government asked if he could expand the team in order to vaccinate all of Western Samoa. Within 48 hours, Green enlisted 76 medical personnel and got 50,000 vaccines from UNICEF. He convinced Hawaiian Airlines to provide a plane, a local energy company donated fuel, “and I bought the beer,” Green said.

They vaccinated 36,997 people in two days. It was the “experience of a lifetime,” Green recalled. “And then who would have known that we would have an outbreak of coronavirus and COVID would sweep across the globe six weeks later?”

Informing the public

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Green and others criticized Hawaii’s state Health Department for slow implementation of testing and other measures needed to control the virus’ spread. Eventually the state’s health and public safety directors stepped down.

But in the meantime, Green felt officials weren’t releasing data in a timely fashion. Since he was getting daily updates from 14 local hospital executives, he started putting them on Facebook.

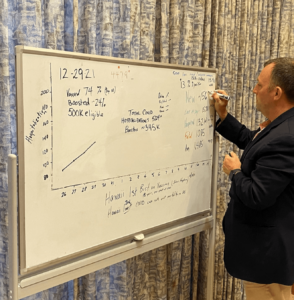

From March 2020 to February 2022, thousands of Hawaii residents logged on to watch Green’s updates. Using a whiteboard for his tallies, his short daily videos showed the number of new cases, hospital admissions, and how many patients were in the ICU, on ventilators, or in the morgue. He thought people deserved to know if their local hospital was full or if there was an outbreak at their child’s school.

Green’s videos ruffled feathers in the governor’s office. Honolulu Civil Beat, an independent news outlet, reported in March 2020 that Ige banned Green from attending meetings and press conferences after Green called the state’s management of the crisis a “total fail.” The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

The election

Green is one of seven Democrats running for the party’s nomination in the Aug. 13 gubernatorial primary, but polls show him with a substantial lead. (Ige is term-limited and cannot run again.)

Green’s rivals include Hawaii Congressman Kai Kahele and Vicky Cayetano, wife of former Hawaii Gov. Benjamin Cayetano. They did not respond to requests for comment on this story. But Cayetano has made allegations of ethical lapses against Green in an ad, while Kahele’s campaign has been criticized for using a caricature in an ad against Green that some say resembles Hitler. “It’s anti-Semitic and has no place in Hawaii or anywhere in the country,” Rabbi Itchel Krasnjansky was quoted as saying by Hawaii News Now. Kahele says the meme was not intended to “harbor any hateful speech.”

Nearly 60% of Hawaii voters are Democrats or lean that way, and Politico predicts that whoever wins the Democratic primary will win the general election.

The ADL speaks out

Hawaii has historically been an easy place for Jews to live, with a small but active Jewish community. Generally, Jews here live peacefully alongside members of many different religions — Muslim, Buddhist, Christian and more.

So Jewish residents were shocked when they learned of the antisemitic harassment Green experienced when the pandemic began. The Anti-Defamation League even put out a statement condemning the slurs used against him, and lauded his work on “the urgent need to safeguard public health.” The statement noted that extremists “have blamed Jews for the pandemic’s spread. The escalation in antisemitic rants and Holocaust analogies tied to anti-vaccine and anti-masking protests is as alarming as it is inaccurate and offensive.”

Looking ahead

If Green is elected governor, he will have to give up his ER weekend job, but he’ll have plenty to keep him busy. His vision includes instituting paid family leave, same-day access to drug treatment, and a “true livable wage.” He proposes legalizing and taxing cannabis, then using that revenue to pay for public health needs and education.

Bringing more doctors to Hawaii is another of Green’s priorities. On some islands, there are 40% fewer doctors than there should be for the population. And he has an idea for solving the problem: Offer “global loan repayment for doctors and nurses who stay here for five years.” Green believes the initiative would pay for itself since the state has a high Medicaid population need. “It would make Hawaii the most attractive place to practice in the country,” he said.

“It’s a big lift,” Green admitted. “But after seeing COVID run through us, I don’t see why we couldn’t handle anything.”