10 Jewish baseball players from history who you may not know (but should)

Sandy Koufax wasn’t the only Jewish player to leave a mark on the game in the 20th century.(Wikimedia Commons/Getty Images/Design by Mollie Suss)

(JTA) — Jewish (and many non-Jewish) baseball fans know the names and achievements of Sandy Koufax and Hank Greenberg, along with their hallowed status in the greater American Jewish history books.

But they were far from the only Jewish ballplayers to make an impact on the game over the course of the 20th century.

Howard Megdal, who writes for Baseball Prospectus and extensively on women’s sports, released an updated version of his 2009 book “The Baseball Talmud: The Definitive Position-by-Position Ranking of Baseball’s Chosen Players” in May. To mark the moment, we’ve highlighted 10 less heralded players from its long list — all who played well before contemporary Jewish baseball stars like Alex Bregman and Max Fried were born.

They are presented here in alphabetical order (by last name), along with the years they played, the teams they played for and their notable stats.

A photo of the Morrie Arnovich 1940 Play Ball card. (Wikimedia Commons)

Morrie Arnovich, OF (1936-1941, 1946)

Philadelphia Phillies, Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants

.287 batting average, 261 runs batted in

Born in 1910 in Superior, Wisconsin, Arnovich’s parents pushed him to become a rabbi. Needless to say, he had other ideas. Arnovich, who was reportedly nicknamed “Son of Israel” in the Jewish press, played five full seasons with the Philadelphia Phillies, Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants before he enlisted in the army in 1942, after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He made the National League All-Star team in 1939 with the Phillies, hitting .324 with 67 RBI. During his career, Arnovich hit for a high batting average and played great defense, compiling an impressive fielding percentage of .981. After his playing days, he returned to Superior, where he coached at a local Catholic high school. He died of a coronary artery blockage at 48 and was buried in Superior’s Hebrew Cemetery.

Mike Epstein smiles for the camera, June 5, 1967. (Getty Images)

Mike Epstein, 1B (1966-1974)

Baltimore Orioles, Washington Senators/Texas Rangers, Oakland Athletics and California Angels

.244, 130 home runs

Nicknamed “Superjew” by an opposing minor league manager, Epstein was the premier Jewish slugger of his era. He was an All-American in college at the University of California-Berkeley and won a gold medal with the U.S. Olympic team before the Baltimore Orioles signed him for $20,000 in 1964. Even though he played in spacious parks his entire career and never hit for a high average, he flashed home run power, hitting 19 or more homers in four seasons.

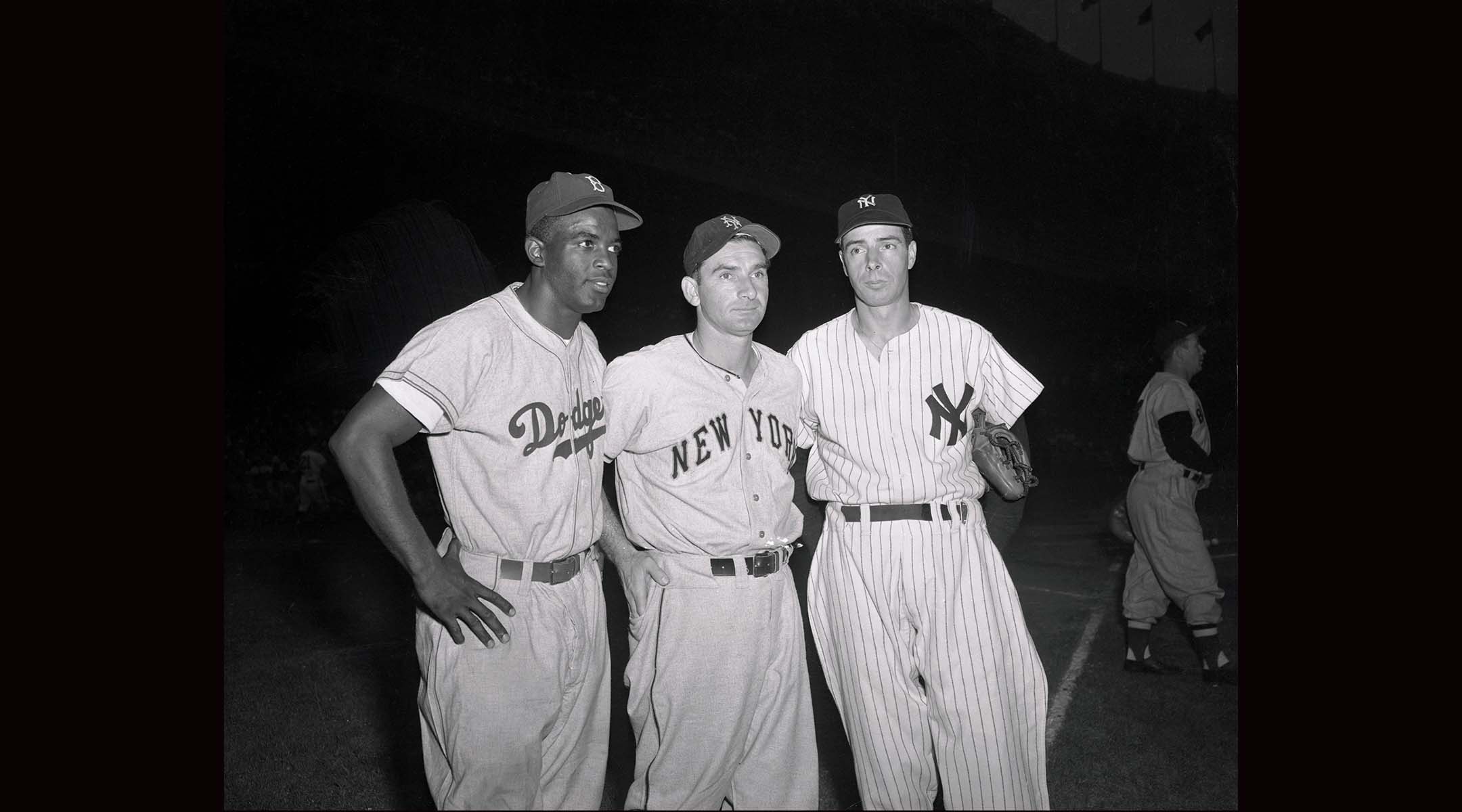

Sid Gordon, center, shown with the legends Jackie Robinson and Joe DiMaggio in 1949. (Getty Images)

Sid Gordon, OF (1941-1943, 1946-1955)

New York Giants, Boston/Milwaukee Braves and Pittsburgh Pirates

.283, 202 HR

When Gordon returned from serving in the Coast Guard in 1946, he started a run of nine seasons in which he was one of the best players in baseball for the New York Giants, Boston (and Milwaukee) Braves and Pittsburgh Pirates. Each year from 1948 to 1951, he hit 26 or more home runs, drove in 90 or more runs, and hit .284 or above. His finest season came in 1948, when he hit .299 with 30 homers and 107 RBI. When the Brooklyn Dodgers, looking for a Jewish player, signed Sandy Koufax, team owner Walter O’Malley said that he hoped Koufax could be as good as Hank Greenberg or Sid Gordon. During a game against the St. Louis Cardinals in 1949, he was hit with antisemitic insults from the opposing bench, spurring Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer to reportedly rebuke his team by saying “Sid is a friend of mine.”

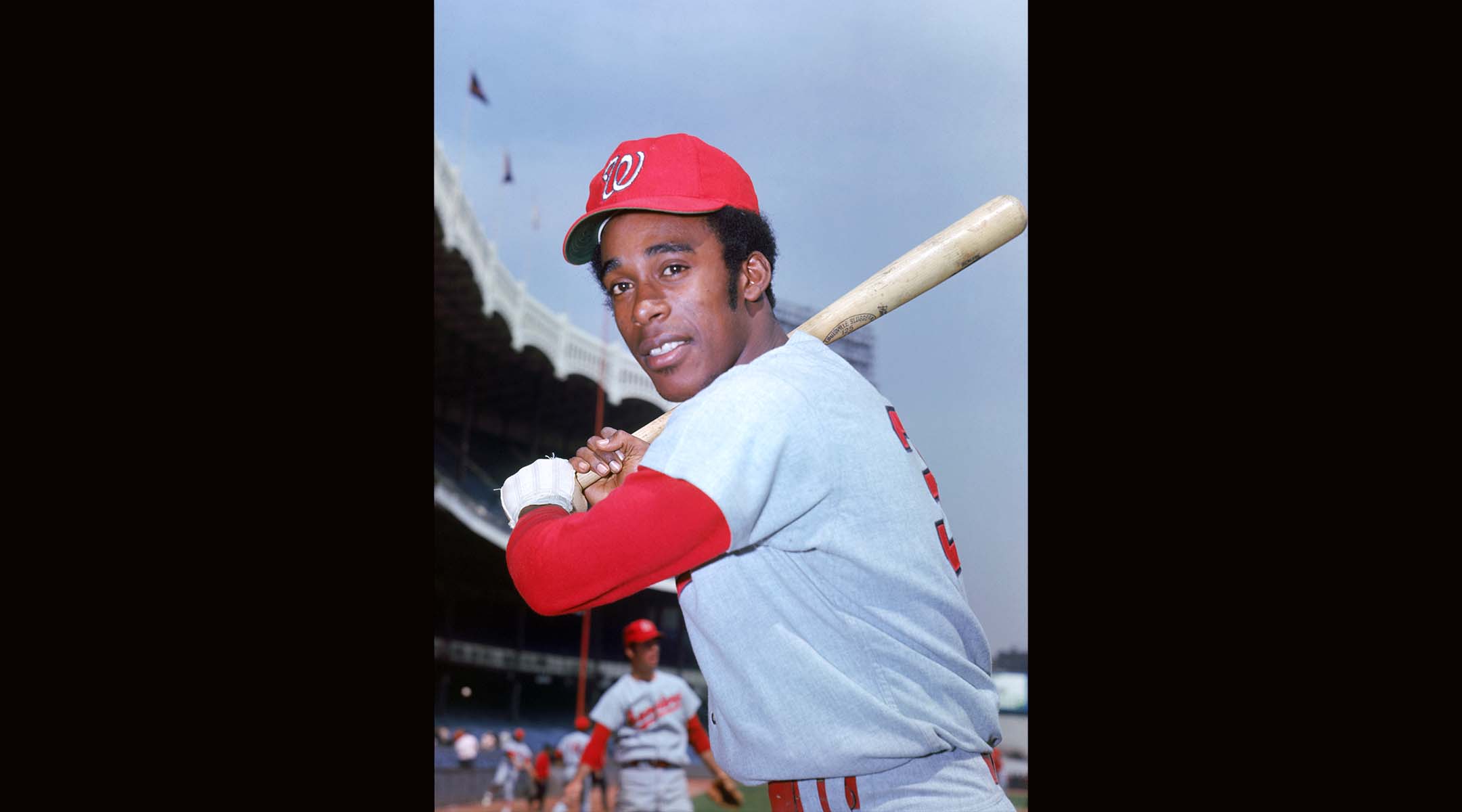

Elliott Maddox of the Washington Senators poses for a portrait in 1971. (Louis Requena/MLB via Getty Images)

Elliott Maddox, OF (1970-1980)

Detroit Tigers, Washington Senators/Texas Rangers, New York Yankees, Baltimore Orioles and New York Mets

.261, 234 RBI

Before he tore up his knee in 1975, Maddox was considered the best defensive center fielder in the American League. He could also hit for average, hitting .304 from the beginning of 1974 until he got hurt in 1975, and showed excellent plate discipline, consistently walking more than he struck out. Maddox, born an African American Baptist, took Judaic Studies classes at the University of Michigan and converted to Judaism before the 1974 season. He said, “I did receive an inner peace with converting. I really feel at home.”

Check out our Jewish sports newsletter.

Erskine Mayer, right, show with his Phillies teammate Otto Knabe in 1913. (Wikimedia Commons)

Erskine Mayer, RHP (1912-1919)

Philadelphia Phillies, Pittsburgh Pirates and Chicago White Sox

91-70 record, 2.96 earned run average

Mayer finished his career with the infamous Chicago Black Sox of 1919 — as one of the players who did not get caught throwing World Series games. In 1913, at the age of 23, Mayer began a streak of six straight seasons with an ERA (earned run average) of 3.15 or below. In 1915, he recorded a 2.36 ERA as the No. 2 starter behind the great Grover Cleveland Alexander, as the Philadelphia Phillies won the pennant. In Game 2 of the World Series, he pitched a complete game, giving up only one earned run. His career ERA of 2.96 is the third-lowest ever for a Jewish pitcher, behind only Barney Pelty (see more on him below) and Koufax.

Dave Roberts, circa 1977. (Wikimedia Commons)

Dave Roberts, LHP (1969-1981)

San Diego Padres, Houston Astros, Detroit Tigers, Chicago Cubs, San Francisco Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, Seattle Mariners and New York Mets

103-125, 3.78 ERA

Roberts was a very good starter and reliever when he stayed healthy. From 1970 to 1974, he won 61 games with an ERA of 3.22 for some mediocre-to-bad San Diego Padres and Houston Astros teams. In 1979, the Pittsburgh Pirates acquired Roberts for the stretch run and he pitched very well in 38.2 innings, helping Pittsburgh win the World Series. In 1971, he went only 14-17 for the Padres as they lost 100 games, but he finished with a 2.10 ERA and was sixth in NL Cy Young award voting for the league’s best pitcher.

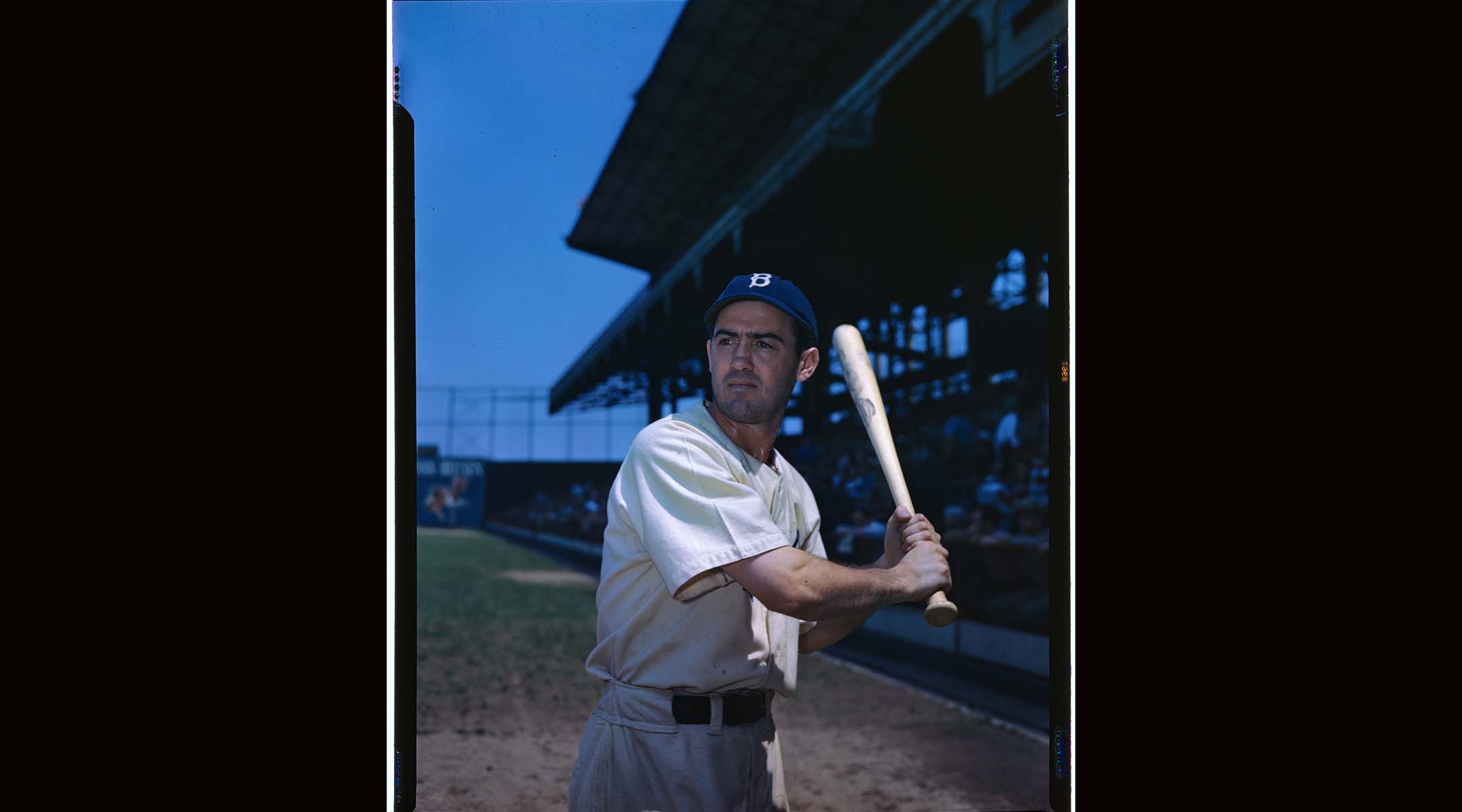

George “Goody” Rosen, a baseball player with the Brooklyn Dodgers, is shown ready to swing the bat. (Getty Images)

Goody Rosen, OF (1937-1939, 1944-1946)

Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants

.291, 197 RBI

Although he played in the minor leagues for most of his prime, Rosen made an impact in the big leagues for the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants, combining high batting averages with excellent defense. Rosen started professional ball in 1932, but he stayed in Double A for five seasons, despite hitting between .293 and .314 and playing great defense in center field. He made it to the show in 1937 and played well in part-time duty for three seasons before he was sold to Columbus in the American Association, and he stayed in the minors for four years. In 1944, Rosen got another chance and in 1945 he took off, hitting .325 and earning an All-Star appearance. Born in Toronto to Russian immigrants, he reportedly expressed pride at being the first Canadian Jewish baseball player in the major leagues, a distinction he would hold for several decades.

A digitalized copy of a Barney Pelty baseball card for the American Tobacco Company, 1909-11. (Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Barney Pelty, RHP (1903-1912)

St. Louis Browns, Washington Senators

2.63 ERA, 693 strikeouts

Called “The Yiddish Curver” — a nickname that he enjoyed having — for his nasty curveball, Pelty had a successful 10-year career with the St. Louis Browns, as well as 11 games with the Washington Senators. He recorded an ERA below 2.85 his first seven seasons, twice finishing below 2.00, an incredibly rare feat in modern times. In 1906, he went 16-11 with a 1.59 ERA, second lowest in the American League. Pelty’s parents were among the first Jews to live in Farmington, Missouri, where Barney grew up.

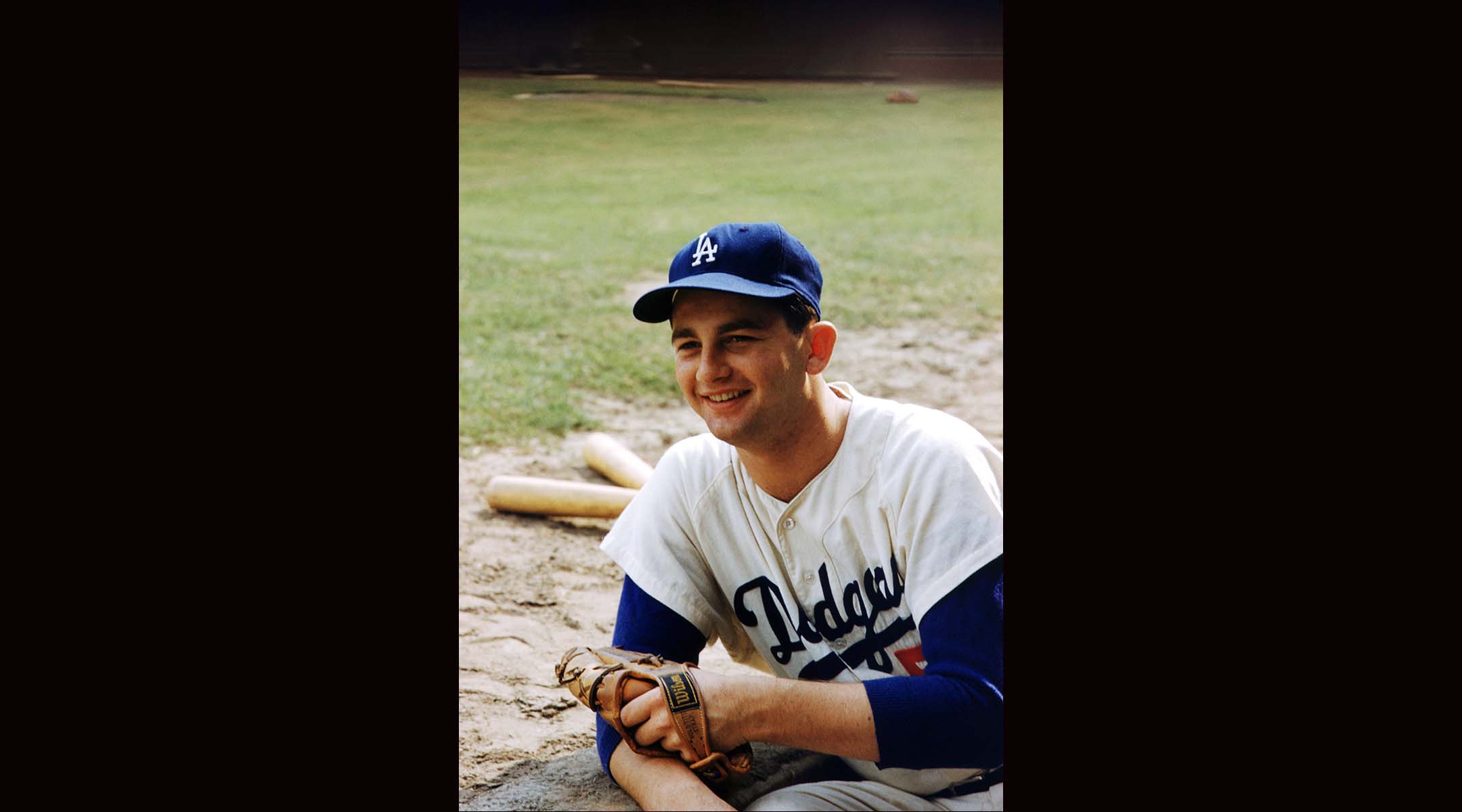

Larry Sherry of the Los Angeles Dodgers sits on the dugout steps before a game during the 1959 World Series in Los Angeles. (Hy Peskin/Getty Images)

Larry Sherry, RHP (1958-1968)

Los Angeles Dodgers, Detroit Tigers, Houston Astros and California Angels

53-44, 3.67 ERA

Sherry came up to the big leagues as a starter but the Dodgers quickly turned him into a reliever. He posted eight solid seasons from 1959 to 1966 with the Dodgers and the Detroit Tigers, finishing with an ERA below 3.00 each year. In the 1959 World Series, Sherry won two games while pitching in relief, including the decisive sixth game, as the Dodgers overcame the Chicago White Sox. As Dodger teammates between 1959 and 1962, Sherry and his brother Norm formed one of the few Jewish pitcher-catcher batteries in baseball history, and the first (and to this day the only) Jewish brother battery.

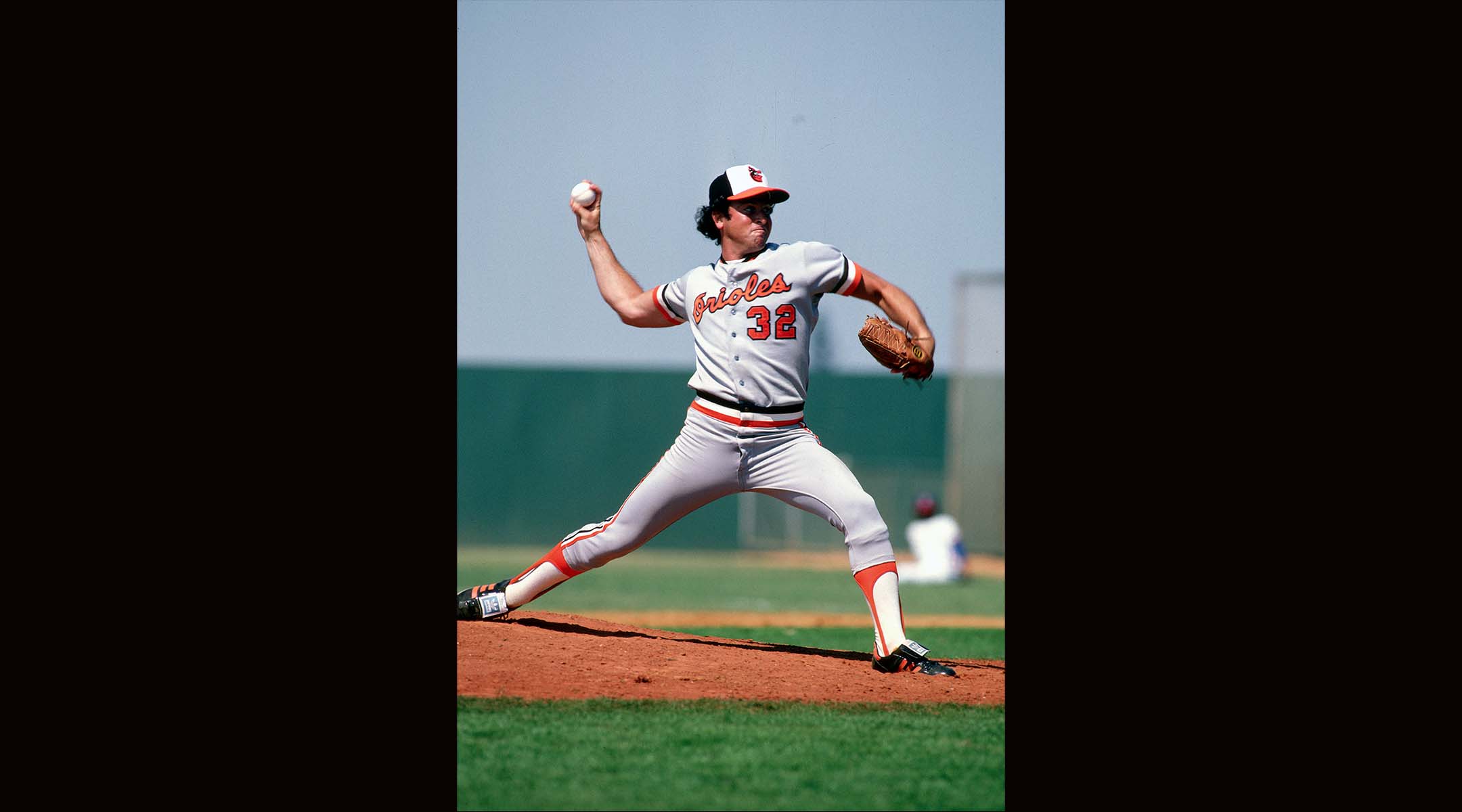

Steve Stone of the Baltimore Orioles pitches during a Major League Baseball spring training game, circa 1981. (Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

Steve Stone, RHP (1971-1981)

San Francisco Giants, Chicago White Sox, Chicago Cubs and Baltimore Orioles

107-93, 3.97 ERA, 1980 Cy Young Award

When Stone debuted in 1971, Larry Jansen, a Giants coach, called him “the most promising young pitcher we’ve seen since Juan Marichal came up.” In 1980, Stone put together one of the most surprising seasons in baseball history. After finishing with an ERA below 3.95 only once in the previous seven seasons, Stone went 25-7 with a 3.23 ERA for the Baltimore Orioles, winning the American League Cy Young award. Writer Ron Fimrite, in the May 17, 1971, issue of Sports Illustrated, labeled Stone “a Jewish intellectual … who just might be a right-handed (Sandy) Koufax.” Stone would go on to become a longtime TV commentator for the Chicago Cubs and later the Chicago White Sox.

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30