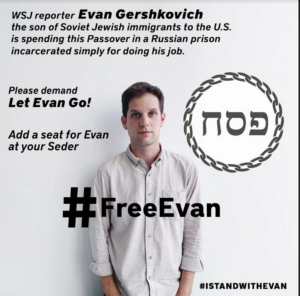

#FreeEvan movement takes off on social media for American Jewish reporter jailed in Russia

Sharansky and Griner speak out; photos of Seder plates set for Evan Gershkovich abound, echoing the movement to free Soviet Jews

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Efforts to publicize the plight of Evan Gershkovich, the Wall Street Journal reporter imprisoned in Russia, are growing and have begun to echo the historic campaign to free Soviet Jews.

High-profile individuals like Natan Sharansky and Brittney Griner are speaking out about the case. And in a gesture that recalled the famous “Freedom Seders” held in the 1960s and ’70s to support Jewish “refuseniks” in the Soviet Union, Jews around the world set an extra seat at their Seders in Gershkovich’s honor as Passover began Wednesday night.

On Thursday, the National Press Club awarded Gershkovich its highest honor for press freedom, the John Aubuchon Award. The club said Gershkovich “has reported with dedication and courage from Russia since 2017, despite the dramatic increase in danger for journalists.” The award is usually given at the end of the year, but the press club announced it now to support his cause.

Gershkovich is the first American journalist to be detained by Russian authorities since 1986.

Sharansky and Griner

Sharansky, 75, the dissident whose imprisonment was a cause celebre in the Soviet Jewry movement, released a video in support of Gershkovich. Gershkovich, who was born and raised in the U.S., is himself the son of Soviet Jewish émigrés. His mother grew up in St. Petersburg and his father is from Odesa, in Ukraine.

Gershkovich was arrested March 29 on espionage charges that his supporters and the U.S. government say are false. He is being held in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, where Sharansky spent 18 months of his nine-year incarceration.

“It’s KGB prison and they’ll make sure that you know nothing about what’s happening in the world and the world will know nothing about what’s happening until they want the world to know,” Sharansky said.

Sharansky urged “the leaders of the free world” to “press on Putin,” adding: “The Russian authorities are testing whether their bluff is accepted by somebody, whether there is hope that people will be hesitant to speak out.” They must be shown that “there is no chance they will gain from this.”

Griner, the U.S. basketball star who was imprisoned in Russia for 10 months last year, accused of bringing cannabis oil in vape cartridges into the country, posted a message on Instagram with her wife Cherelle, expressing “great concern” for Gershkovich. “We must do everything in our power to bring him and all Americans home,” they wrote. “Every American who is taken is ours to fight for and every American returned is a win for us all.”

Griner was released in a prisoner swap for Russian arms dealer Victor Bout. But the U.S. has been unable to free another American, Paul Whelan, who’s serving a 16-year sentence on espionage charges that his supporters say are false.

Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales also spoke out, tweeting: “Everyone please be aware of and keep highlighting what is going on with WSJ reporter Evan Gershkovich. Journalism is not a crime.”

Several U.S. senators and members of Congress also condemned Gershkovich’s detention as “a fabricated criminal case” and “an excuse to take an American citizen hostage.”

Letters pouring in

Another effort to help Gershkovich is an email account, [email protected], where anyone can send a message of support. Hundreds of letters have already poured in, according to Polina Ivanova, a journalist now with the Financial Times who worked with Gershkovich when he started reporting from Moscow in 2017. She declined to give details on how the letters are being delivered, but said: “They are on their way to him.”

Meanwhile Gershkovich’s colleagues around the world have launched grassroots campaigns to bring attention to his case. The idea for Seder place settings originated with a conversation between Jared Malsin, a Wall Street Journal reporter based in Turkey, and his wife, Guardian reporter Ruth Michaelson. They typically ask Seder guests to bring something to read on the theme of freedom, so a discussion of Gershkovich’s plight was a natural fit. Michaelson said that led to, “Why don’t we set a place for him?”

The Passover initiative

“If we’re going to talk about what freedom means, it’s impossible to have that conversation at the moment without thinking of our colleague who’s in prison,” she said.

The idea took off after Shayndi Raice, the Journal’s deputy bureau chief in the Middle East, tweeted about it April 1, saying: “Please consider setting an extra setting at your Passover Seder for #EvanGershkovich, my @WSJ colleague who is being held hostage by Russia.” Enthusiasm for the initiative came not just from individuals but also from nonprofits like JewBelong and JCCs, along with Israeli and Jewish news outlets. Social media was flooded overnight with photos from Seders tagged #StandWithEvan and #FreeEvan.

Among those images was a place setting from the home of Francine Smilen, who set a handwritten card atop a plate with a Haggadah that read: “EVAN. With hope and love.”

Smilen is the mother of a Journal reporter and is herself the child of a Holocaust survivor. She told her Seder guests that “another meaning of the Hebrew word for Egypt, Mitzrayim, is ‘a narrow space.’ We’ve all come out of our own narrow spaces, and Evan is now in a very narrow space.”

Raice also tweeted a photo from Rabbi Elliot Pearlson at Temple Menorah in Miami Beach, Florida, showing a seat for Gershkovich on the synagogue’s bimah, draped with a tallit, bearing his photo and the words in Hebrew and English, “Set our brother free!”

I’m in tears. The pictures are starting to come in. This is from Temple Menorah in Miami Beach, Fl., which has set a seat for @evangershkovich on the synagogue’s bimah. Thank you Rabbi Elliot Pearlson. Please keep sending me pictures! #IStandWithEvan pic.twitter.com/UvkEd9f6S9

— Shayndi Raice (@Shayndi) April 5, 2023

Echoing the Soviet Jewry movement

Empty seats in synagogues is also a ritual with roots in the struggle to free Soviet Jews, according to Shaul Kelner, a professor of sociology and Jewish studies at Vanderbilt University who is working on a book about that movement.

“This effort to advocate for Evan’s freedom echoes what activists were doing in the movement to free Soviet Jews for many, many years,” he said. The movement initially focused on Seders as a way to bring the cause “off the streets and into the home,” not only because the holiday is themed on liberation, but also because “if you want to mobilize Jews when they’re gathering and thinking Jewishly, getting them at Seders is the time to do it.”

The holiday rituals began in the 1960s with a designated “matzo of hope” along with the empty Seder place settings, “symbolic of the Soviet Jew who was not able to be with them,” Kelner said. But soon the “empty seat” was being showcased at synagogues, at congregational Seders and on the bimah, and later even at bar and bat mitzvah celebrations.

Gershkovich’s dedication as a journalist

Malsin met Gershkovich during a 2022 training course for journalists working in war zones and other hostile environments. “One of the last nights in the course, we were all eating dinner together, and there were a few of us who were American Jews, all reflecting on rediscovering Eastern European and especially Russian and Ukrainian heritage,” Malsin said. “That was something he talked about — the story of his parents, who came over in 1979, fleeing the Soviet Union. He grew up in New Jersey but had this lifelong fascination with Russia and the broader post-Soviet world. He moved to Moscow as an adult to pursue that.”

Ivanova said Gershkovich is “an absolutely fantastic reporter,” a “decent, honest, careful journalist who embraces the nuances of every story, which is really important covering a place as complex, as dense, as difficult as Russia. He never wanted to shy away from bringing out those nuances.” Instead, his work forced readers to confront “what it’s like to live under an authoritarian regime.”

Ivanova is not Jewish, but said she and Gershkovich “had lots of parallels” in their family stories around their “mixed identity.” She was born in St. Petersburg but left at age 3 with her mother and grew up in England. She noted that Gershkovich did a “super brave thing,” giving up an entry-level job at The New York Times and taking one at the Moscow Times because “his dream was to cover Russia.” He moved to the Journal in 2022.

She noted that Gershkovich was fully accredited by the Russian Foreign Ministry, “which is an official greenlight to work as a journalist” there. His arrest, she added, has “a huge chilling effect” on other journalists.