Inspired by Chabad and a teenage mom, he’s given more than a million books to kids in need

BookSmiles is now one of the largest book banks in the nation

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Larry Abrams grew up in the only Jewish family in the tiny, mostly Catholic town Tupper Lake, New York, in the heart of the Adirondacks and 35 miles from the nearest synagogue. But Chabad managed to find them, and gift the not-very-religious Abrams with a bundle of Jewish books.

The unsolicited present made an impression on Abrams, now 55, who read the books, spent time at the Chabad House as a University of Rochester student in the 1980s, and even considered becoming Orthodox. But it also planted the seeds for a passion project that neither Abrams nor the Chabad emissaries could have predicted.

Today Abrams heads BooksSmiles, a nonprofit “book bank,” which he founded five years ago to serve children who have few books in their lives. Abrams expects to give away its 1.5 millionth book in the next few months. Of the more than 70 such nonprofits in the U.S., he said, BookSmiles gives out more books than nearly all of them.

He operates BooksSmiles out of a 4,300-square-foot warehouse in Pennsauken, New Jersey, just east of Philadelphia. It opens its doors every Sunday to teachers, most of whom struggle to stock their classroom libraries, and some of whom travel from as many as two hours away to collect boxes of books divided by age level — from board books for babies to challenging reads for high schoolers.

CNN broadcast a seven-minute profile of Abrams and BookSmiles last year, which helped boost its reach and publicize the retired high school English teacher’s philosophy: Cultivating a love for books in children can help lift them out of poverty. But though Abrams appreciated CNN’s attention, he said its BookSmiles feature did not convey the essential Jewishness of the project’s origin and character.

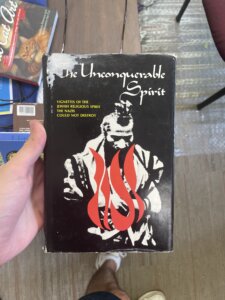

One of the books Chabad delivered to his boyhood home, The Unconquerable Spirit by Simon Zucker, now sits on the shelf at the BookSmiles office. It’s about how Judaism sustained victims of the Holocaust.

“I read the thing and was deeply impressed,” he said. “But I was even more impressed by these emissaries, these Chabad guys, specifically finding us and giving us books.”

“It really sparked something in me,” he added.

Abrams is now the emissary, on a mission to irrigate “book deserts,” he said. “Every Jew should be able to understand that … we can all become ‘People of the Book’.”

Baby needs a book

Abrams, whose parents’ identified with the Reform movement, has always associated reading with Judaism.

“It’s what defines us as a people: cramming our homes with books and printed material,” he said.

After high school, he went to the University of Rochester on an ROTC scholarship, served in the Navy and settled outside Philadelphia to take up his life’s work: teaching. Abrams spent 18 years at Lindenwold High School, just outside the city in New Jersey, teaching English to freshmen and a senior projects class. Most of Lindenwold’s students were eligible for free lunch, and many lagged in reading, some as many as six grades behind.

Abrams, who married and had two children, joined a Conservative synagogue, Congregation Beth El in Voorhees, New Jersey, which would later provide critical support to the fledgling effort that would eventually become BookSmiles.

The immediate impetus for his book collecting came in 2014 from his classroom. He asked a student, a new mother, whether she read to her newborn. She thought his question strange — why read to a baby? But Abrams explained how reading to even the youngest children can give them a head start in life, and began to collect board books for the student’s daughter. He turned to friends and family, asking for book donations so other teachers could do the same. His one-car garage soon filled up with thousands of books, many donated by Beth El congregants.

He soon realized that the project needed more space and funding, and again his shul came through. One member advised: “Become a nonprofit, and then I can give you a check,” and followed through with a $100.

Abrams took that advice and his son, a high school senior at a time, blurted it out a possible name for the new nonprofit: “BookSmiles.”

“I thought it was brilliant,” Abrams said.

How to collect 75,000 books

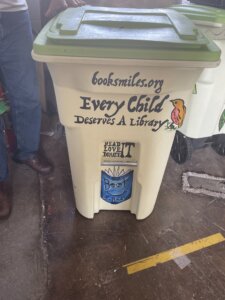

The 75,000 books that BookSmiles receives every month come from loyal supporters who volunteer to collect books in their communities. BookSmiles also collects books in 110 colorfully painted and BookSmiles-branded outdoor garbage bins placed in front of schools and mom-and-pop shops, particularly in affluent districts between the Main Line and the Jersey Shore. This summer, Abrams began replacing some of the plastic bins with larger and sturdier metal donation containers, and installed the first outside Congregation Beth El.

Once the books make it to the Pennsauken warehouse, they are sorted by BookSmiles’s hundreds of volunteers, who ensure that they are in good condition. Damaged books can put off young readers, he said.

In the mounds of donations, volunteers often find valuable volumes, which BookSmiles sells to bolster its annual budget, which is now about $250,000 and supports five employees — three full-time, including Abrams, and two part-time.

Rummaging through a bin of donations one day, Abrams found a signed first edition of a Harry Potter novel, the sale of which could pay for dozens of not-so-rare Harry Potter paperbacks to stock BookSmiles’s shelves.

‘The key’ to solving poverty

BookSmiles, which has held several fundraising campaigns, has received financial support from the independent publisher Townsend Press, The Kramer Foundation and the Justamere Foundation, among other groups. This month, New Jersey state Sen. Troy Singleton sponsored a budget resolution to appropriate $25,000 to BookSmiles, in recognition of its work in his district.

Abrams retired last year after three decades in the classroom to devote more time to BookSmiles. But he tries to stay in touch with his students.

He learned a year ago that the high school senior who inspired him to begin BookSmiles is now the mother of an honor-roll student whose favorite subject is English.

BookSmiles is how Abrams said he practices tikkun olam, Hebrew for “healing the world.”

“You can keep feeding people,” he said. “But it doesn’t do much to stop intergenerational poverty. Giving books to kids does it. That’s the key.”

He dreams of projects like BookSmiles across the nation, but not a national organization. He’d like others to start gathering and distributing books in their own neighborhoods. “Call it something else. Don’t use our brand,” he said. “It has to be someone who knows the community. I know Philadelphia, I know South Jersey.”

And he hopes others draw on their life experiences to build book pipelines. His own inspiration is Jewish.

“My Judaism pushes me to do this stuff,” he said. “Don’t throw precious things in the garbage. Figure out how to get them to people who need them.”