Monuments to Nazis hiding in plain sight near Philadelphia and Detroit

The unit perpetrated war crimes, but the memorials suggest they were mere freedom fighters

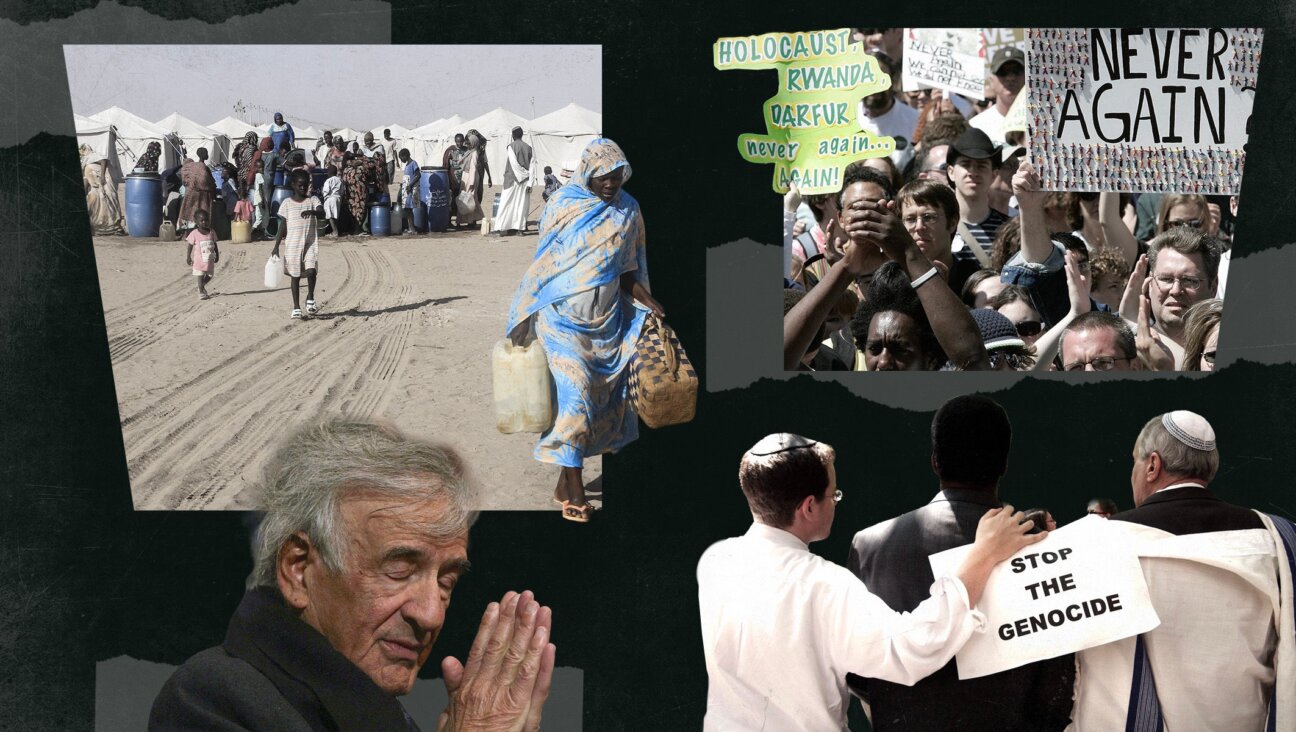

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Editor’s note: This article is part of a years-long project documenting more than 1,600 monuments and streets honoring Nazis and their collaborations across 30 countries.

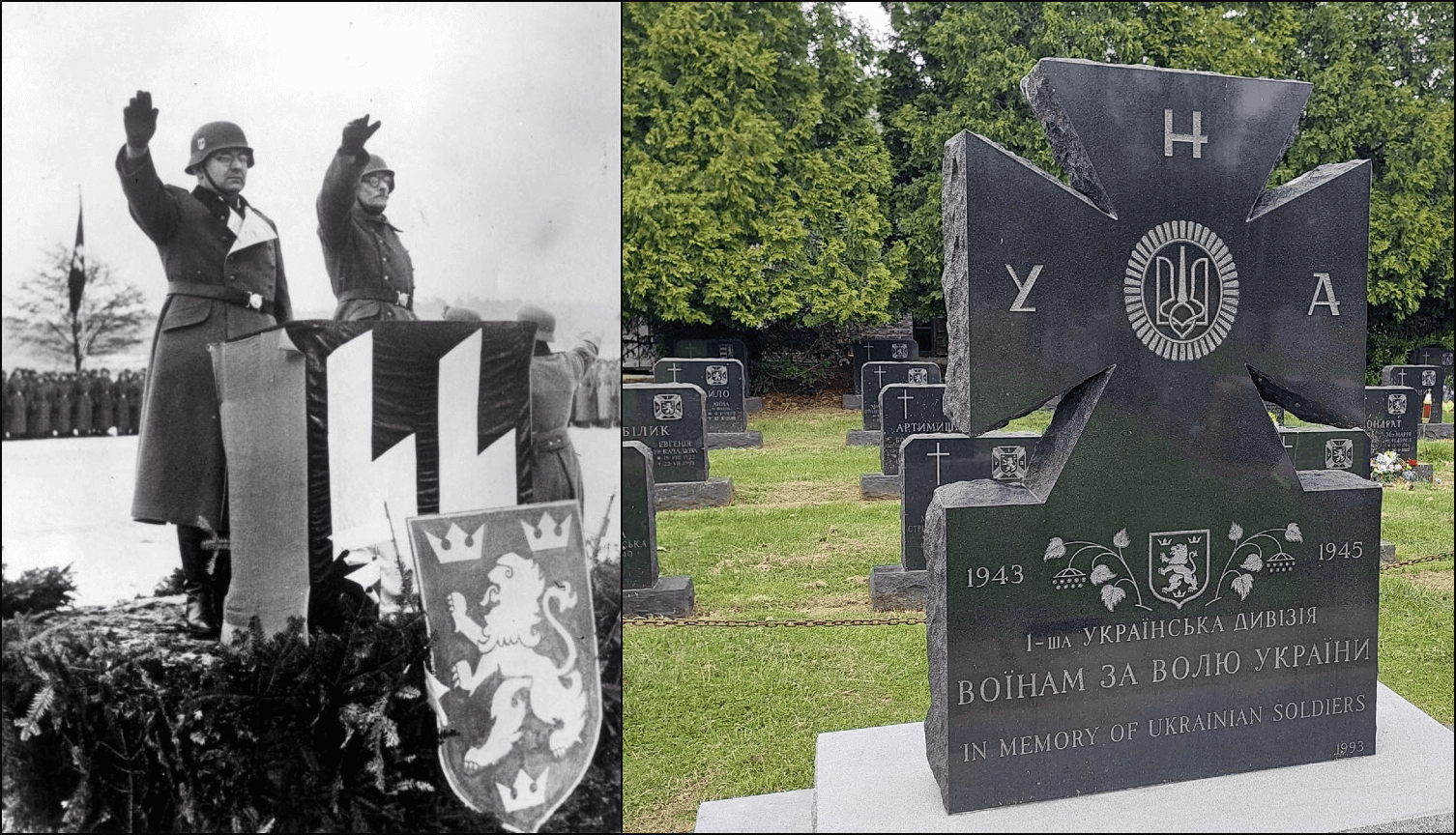

Two monuments to a Nazi military division with a record of war crimes have been hiding in plain sight in the suburbs of Philadelphia and Detroit. Both honor the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician), commonly known as SS Galichina.

Formed in 1943, SS Galichina was a Ukrainian unit in the Waffen-SS — the combat branch of the SS (Schutzstaffel) wing of the Nazi Party. Such units “were heavily involved in the commission of the Holocaust through their participation in mass shootings, anti-partisan warfare, and in supplying guards for Nazi concentration camps,” according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and were “responsible for many other war crimes.”

Marches and monuments honoring SS Galichina in other nations including Canada have been condemned by Jewish organizations and the governments of Ukraine, Germany and Israel. The Forward has over the last three years documented more than 1,600 monuments, memorials and streets honoring Holocaust perpetrators and Third Reich collaborators in 30 countries.

That includes 42 in 16 U.S. states, almost all of which focus on individual Nazi Party members, SS officers or collaborators. (The sole exception is a memorial to the Russian Liberation Army — a unit of Germany’s armed forces — at a convent in upstate New York.)

One of the newly discovered monuments sits in a Catholic cemetery outside Philadelphia, the other on the side of a Ukrainian credit union building in Warren, Michigan, a city of 140,000 people near Detroit.

Asked about the memorial, the mayor of Warren, James R. Fouts, said, “There’s not even a minute chance that we would support anything like this.”

“We would never allow anything like that to go on public property,” Fouts told me, “but I don’t think we can do much for a monument on private land.”

The Philadelphia-area monument, which is more prominent, was revealed in May on Twitter by Moss Robeson, a researcher of Ukraine’s far-right. Its large stone cross bears SS Galichina’s insignia and the inscriptions “In memory of Ukrainian soldiers” in English and “1st Ukrainian Division” and “Fighters for Ukraine’s freedom” in Ukrainian.

(Shortly before the end of WWII, SS Galichina was renamed the 1st Ukrainian Division of the Ukrainian National Army; many similar memorials use this name rather than the one including SS.)

After this article was initially published, the American Jewish Committee issued a statement calling for the Philadelphia monument’s removal. It noted that in the early days after the fall of communism, some Eastern European countries “saw independence as an opportunity to rehabilitate wartime fascist leaders” but that many have since “come to recognize that this is wrong.”

“We trust our Ukrainian friends and colleagues recognize that this cannot remain,” the group said of the Philadelphia monument. “We look forward to being a resource to our partners as they explore how best to condemn and remove this statue.”

The cross sits in Saint Mary’s Ukrainian Catholic Cemetery in Elkins Park, an unincorporated community of about 7,000 some seven miles from the center of Philadelphia. Officials in the township that includes it did not respond to requests for comment.

Next to the cross are numerous graves of SS Galichina veterans with identical tombstones that include the unit’s SS insignia, which the Anti-Defamation League considers a hate symbol.

The memorial has the year 1993 inscribed in a corner. An almanac published by a veterans’ group to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the unit’s founding said it was erected in 1994, and that the group had begun purchasing 90 burial plots for division veterans in 1987.

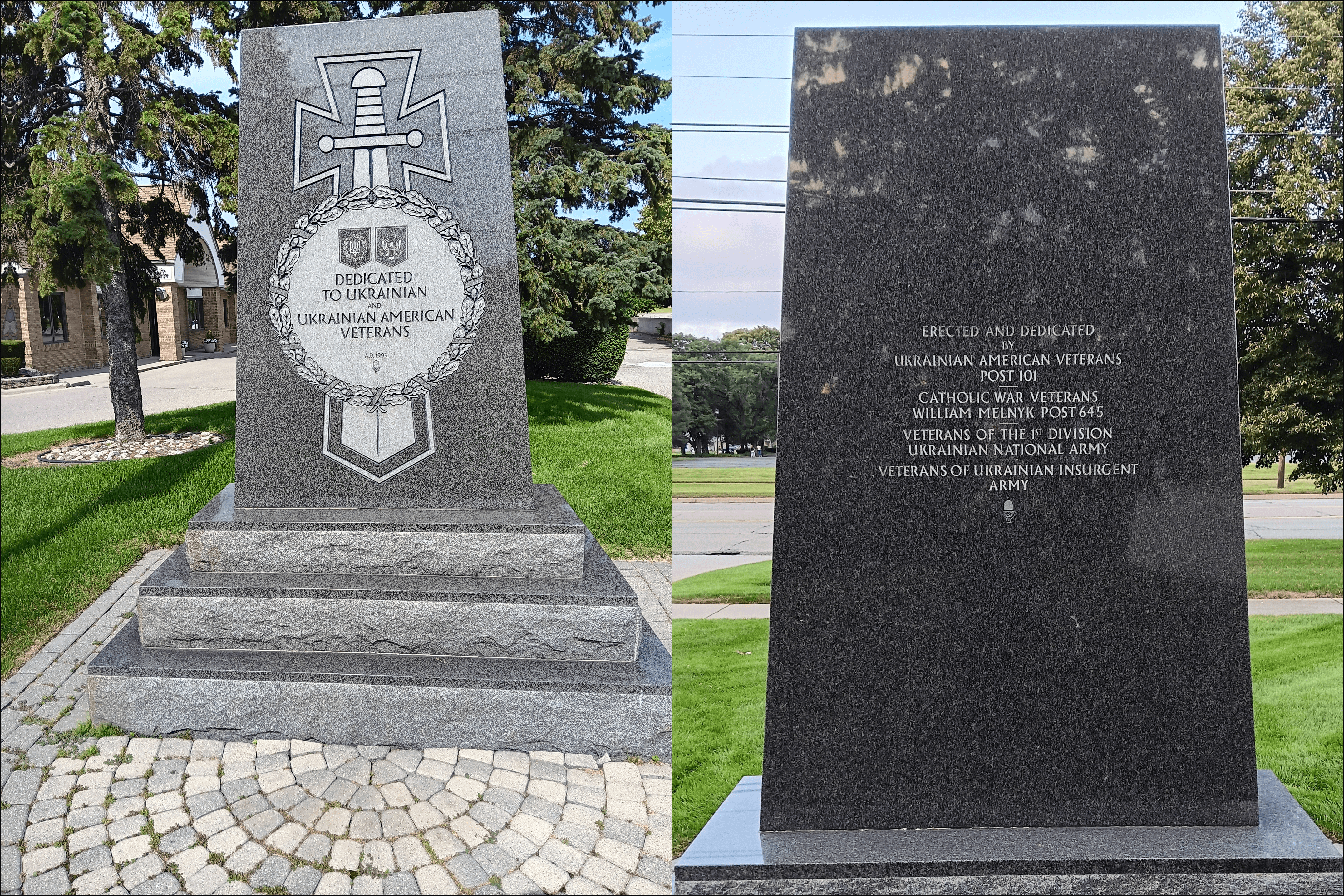

In Warren, the memorial consists of a stone tablet of about nine feet near a main street. The front is inscribed with a sword, a dedication to Ukrainian and Ukrainian-American Veterans, and the year 1993; the back states that it was erected by veterans of several military units including the “1st division Ukrainian National Army.”

The monument appears to honor troops on both sides of the war. A Ukrainian-American veterans’ website says it was erected by an entity called “Post 101” for Ukrainians who served in four different groups, including the U.S. Armed Forces and the 1st Division of the Ukrainian Army — aka SS Galichina.

Marie Zarycky, treasurer of the Ukrainian American Civic Committee of Metropolitan Detroit, insisted the tablet is “not commemorating Nazis.”

“We are commemorating young people who lost their lives attempting to get independence for Ukraine,” she told me. “The common Ukrainian young man that joined the division actually worked for Ukrainian independence, not for success of the Nazis.”

In a 2022 speech for International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Ellen Germain, special envoy for Holocaust issues at the U.S. State Department, warned of the rehabilitation of collaborators who “are considered national heroes because they fought against Soviet tyranny,” an example of Holocaust distortion.

And Efraim Zuroff, director of Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Jerusalem branch, said of the SS Galichina, “The bottom line is that these men were fighting for a victory of the most genocidal regime in history.”

The unit was created in 1943 out of recruits from the Galicia region in western Ukraine. The soldiers took an oath of loyalty to Hitler and were trained by the Third Reich. In May 1944, Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust, inspected the division.

“I know that if I ordered you to liquidate the Poles … I would be giving you permission to do what you are eager to do anyway,” Himmler said during that visit, according to several historical accounts. A few months before, the division had taken part in what historians call the Huta Pieniacka massacre, when SS Galichina subunits burned 500 to 1,000 Polish villagers alive.

Several years after the end of the war in 1945, thousands of SS Galichina fighters who had surrendered to the Allies were freed and allowed to resettle in the U.S., Canada, the U.K. and Australia. The sheer volume of displaced people and postwar chaos made it relatively easy for people to obscure dark pasts and, according to both a 1985 Congressional report and a 2004 CBS article based on declassified documents, U.S. government agencies saw former Nazi collaborators as useful intelligence assets during the Cold War.

These ex-SS Galichina fighters formed veterans’ associations and erected monuments — at least 11 of them in Canada, Australia, Austria and the U.K. have been around for at least 30 years. One, in Feldbach, Austria, had the divisional insignia removed in 2018.

In 2020, B’nai Brith and the Simon Wiesenthal Center called for the removal of those in Edmonton, the capital of the Canadian province of Alberta, and Wayville, a suburb of Toronto, but they both remain standing.

There are also annual marches commemorating SS Galichina in Ukrainian cities including Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk. The ADL condemned a 2018 procession featuring Nazi salutes in Lviv, and in 2021, a march in Kyiv led to denunciations by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the German and Israeli governments.

The cross in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, and tablet in Warren, Michigan, have been added to the Forward’s list of U.S. monuments to Nazis and Nazi collaborators. We have also recently updated our lists for eight other countries.

Recent additions include:

- Two busts of Miklós Horthy, the Hungarian dictator whose country deported hundreds of thousands of Jews to their deaths, in Csátalja and Szekszárd, Hungary.

- A plaque honoring Lithuanian collaborator Kazys Škirpa, who had advocated for the genocide of his country’s Jews, was erected in Vilnius earlier this year, as documented by the watchdog organization Defending History.

Meanwhile, a giant stone Iron Cross, a Third Reich military honor, was toppled in the Czech Republic this March by unknown parties in the middle of the night. There have since been community discussions over whether to return the cross to its original location or perhaps display it in a museum.

Also in March, the Austrian city of Linz renamed a street that had honored SS officer Ferdinand Porsche, who built Hitler weapons and whose factories used slave labor.

If you know of Nazi-related monuments or streets not included in our list, or updates on the status of those that are, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.