After centuries out of sight, the oldest surviving Hebrew Bible is making a permanent move to Israel

The Codex Sassoon, which contains all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, dates from the 10th century

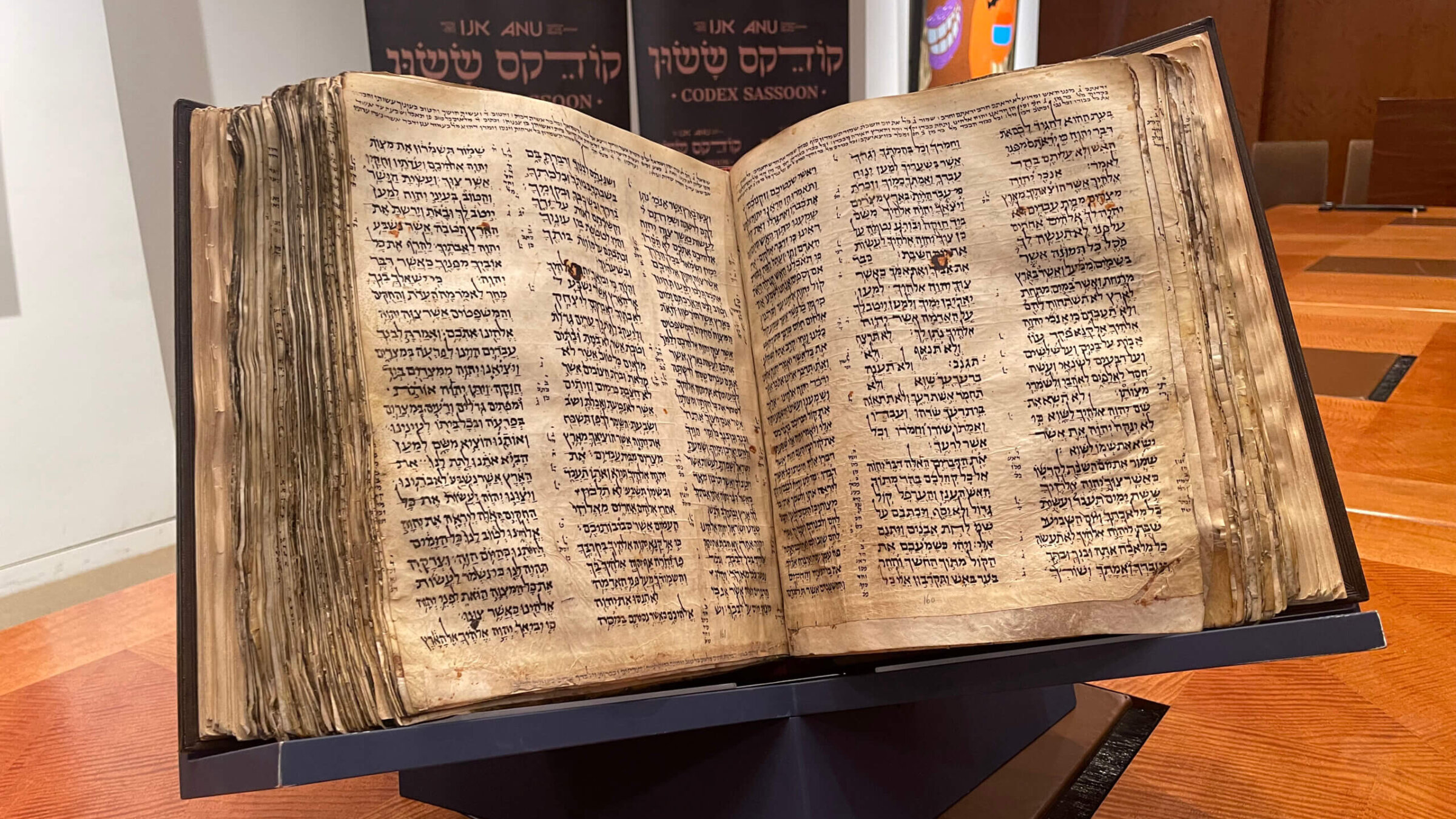

The Codex Sassoon, the oldest surviving copy of the Hebrew Bible, made a permanent move to Israel this week. Photo by Camillo Barone

It was a bittersweet moment for ANU — The Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv. After centuries away from the public eye, the Codex Sassoon, the world’s earliest surviving copy of the Hebrew Bible, was finally on display in Israel — but the display was intended to be temporary, with the Codex’s permanent home not yet decided.

Then, in March, Alfred Moses, 94, learned that the Bible was at the museum on temporary display only. So, he reached out to Shulamith Bahat, CEO of ANU America, and told her he would buy it — with plans to eventually donate it to the museum.

On Thursday, some seven months later, the Codex Sassoon made a permanent move to Israel, with The Museum of the Jewish People set to begin displaying it next week. At least at first, it will be displayed open to the page bearing the 10 Commandments — “the crown of our story,” Bahat said — to represent the universality of the Hebrew Bible.

“I felt something was missing there,” said Bahat, of the museum before the Codex. “Now there is nothing missing. Now the place is complete. It was meant to be.”

On May 17, Moses, an attorney who served as U.S. ambassador to Romania during the Clinton administration, purchased the Codex — which dates from around 900 C.E. and includes all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, and an extensive collection of critical notes to the text known as the Masorah — at auction at Sotheby’s for $38.1 million.

The only other surviving version of the Hebrew Bible to rival the Codex Sassoon in terms of antiquity is the Aleppo Codex, created by the scribe Shlomo ben Buya’a in Tiberias between 925 and 930. But the Codex Sassoon is much more complete: Two-fifths of the Codex Aleppo were lost under mysterious circumstances between 1940 and 1950.

For the first three centuries of its existence, the Codex Sassoon belonged to local Syrian aristocratic families; it was given to a synagogue in Makisin (present-day Markada, northeastern Syria) in the 13th century. Kept in private hands for centuries after that synagogue’s destruction, the Bible reemerged from obscurity when it was sold to British collector David Solomon Sassoon, who owned it from 1929 until 1978.

It then passed into the hands of the British Rail Pension Fund, which sold it in 1989 to private collector Jaqui Safra, who owned it until the May auction.

“The only reason I bought it was to display it publicly in Israel, so that the Jewish people, in effect, own the Sassoon Codex,” said Moses in a Zoom interview. “I feel very privileged to have done that.”

“We had to compete with many great museums and private collectors,” for the Codex Sassoon, said Irian Nevzlin, chair of the board of trustees of the ANU Museum. “It is very important to me that the Codex Sassoon comes home.”

Nevzlin, 45, who was born and raised in Moscow, said that working to install the Codex Sassoon in Israel felt like “closure.”

“I grew up in a house where I wasn’t allowed to know that I was Jewish,” she said. “I didn’t see any Torah or any of the other books ever in my life before the age of 13.”

“I always felt that being Jewish is an honor,” she said. “I always felt that I am stronger because I’m Jewish.”

“Touching the Codex, that is also my Codex, is a celebration of a victory for the Jewish people, and that’s very personal for me.”