Many U.S. synagogues display the Israeli flag on their bimahs. After the hostages were released, one NYC shul decided to move theirs.

Central Synagogue had displayed an Israeli flag since Oct. 7 in honor of the hostages

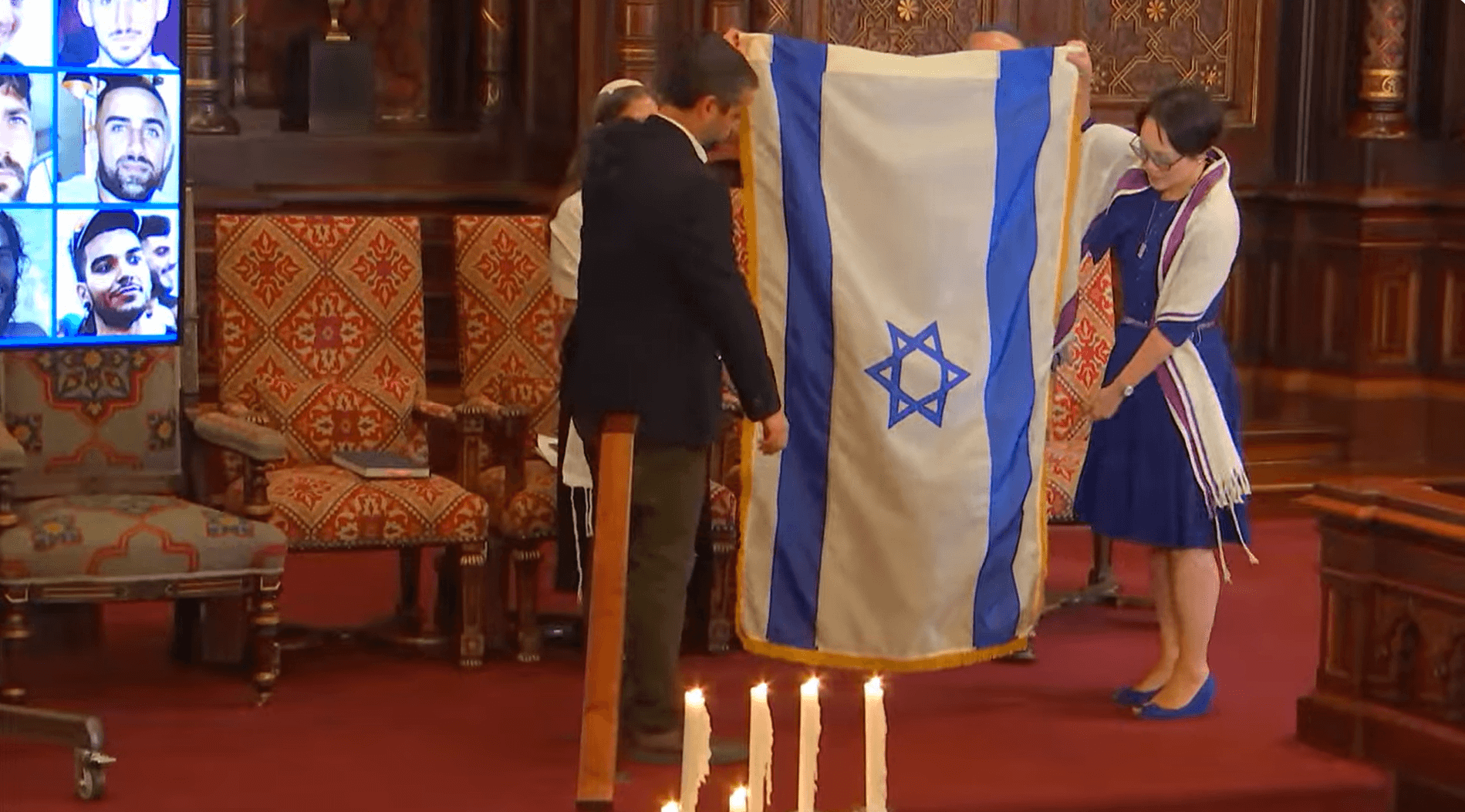

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl and Dagan Shimoni fold the Israeli flag that had been displayed on Central Synagogue’s bimah since the attacks of Oct. 7, 2023. Screenshot of Central Synagogue livestream via YouTube

After the last of the living hostages in Gaza were released last week, a prominent New York synagogue faced a complicated question: Should it remove the Israeli flag on its bimah?

Central Synagogue in Manhattan had displayed the Israeli flag on an empty chair since the attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, along with a count of the days since Hamas killed 1,200 people in Israel and took about 250 hostage.

The Reform synagogue had committed to keeping the flag up “until they all came home,” Rabbi Angela Buchdahl told CBS News.

But after the living hostages had all been reunited with their families, the congregation faced a delicate choice: Is it time to take down that flag? Hamas had not returned the bodies of all deceased hostages, some of whom the group said it is unable to locate. And the Israeli flag’s place on the bimah continued to divide congregants who disagree about the role of the Jewish state in religious services — a debate intensified by Israel’s military campaign in Gaza the past two years.

During last week’s Shabbat service, Buchdahl explained the synagogue’s decision: The flag would be removed from the chair on the bimah — and placed in the Torah ark.

“We must mark this moment ritually,” Buchdahl told the congregation. “We must offer gratitude and celebrate this moment with joy.”

Buchdahl said that in making the decision she drew on customs surrounding Acheinu, the ancient prayer for Jews in captivity. Buchdahl said the prayer has traditionally been invoked only for living hostages. “Our tradition is giving us some guidance in this moment,” she said, “that now that our living hostages are returned we must mark this moment ritually.”

After the congregation said the prayer for hostages, Cantor Daniel Mutlu sang the Skylar Grey song “Coming Home” as news clips of hostages reuniting with their families played on screen. Congregants rose to their feet while Dagan Shimoni, the synagogue’s Israeli shaliach or emissary, and Buchdahl folded the flag and the rabbi placed it in the ark alongside the Torah scrolls.

A different symbol would honor the deceased hostages whose bodies have not been returned. Among them is 19-year-old Itay Chen, who was serving in the Israel Defense Forces when he was killed by Hamas on Oct. 7. Chen’s father, Ruby, had spoken at Central and gifted Buchdahl a dog tag necklace in the aftermath of the attacks.

In honor of Chen and the other deceased hostages, Buchdahl and the clergy placed their dog tag necklaces on a Torah scroll. The necklaces will remain in the Ark until all of the bodies are returned, Buchdahl said.

“We know that there has been so much celebration and joy we saw in that video,” Buchdahl said. “But also so much healing that still needs to happen, for all of those returning, for those who are not returning.”

The flag on the bimah

In her Rosh Hashanah sermon, Buchdahl acknowledged how polarizing symbols like the Israeli flag had become.

“There are members of our own congregation who are disturbed by our weekly prayer for Israel,” she said. “Or who object to the Israeli flag on our bimah, even though the empty chair it covers stands for the 48 remaining hostages whose families still await their return.”

In some ways, Central Synagogue was unusual in its choice not to display an Israeli flag before Oct. 7.

In many U.S. synagogues, the bimah is flanked by both Israeli and American flags. The trend dates back to a wave of patriotism during World War I, when the American flag became common in synagogues and churches, according to Perry Dane, a member of the North American Vexillological Association, which studies flags.

The presence of the U.S. flag inspired some congregations to also display what was then the Zionist flag, Dane said. After Israel’s founding in 1948 — and again after the 1967 War — more synagogues added what became the Israeli flag.

But the presence of the Israeli flag on the bimah has long been debated, sparking discussion among Reform and Orthodox rabbis alike.

A 2015 Forward opinion piece by Alex Kane argued that flags “tether a diverse and opinionated Jewish community to nationalistic sentiments some members don’t agree with: support for the state of Israel and the U.S. government.” A response by Menachem Freedman argued for the Israeli flag, countering that the “political well-being of the state has a well-established place in the synagogue.”

Israel’s military campaign in Gaza over the past two years has made those discussions even more fraught.

This month, on the subreddit Jews of Conscience, which describes itself as “progressive, leftist” and “anti-Zionist,” members discussed whether an Israeli flag on the bimah would be a deterrent for attending a synagogue — and whether to confront a rabbi about removing it.

“This is not hypothetical for me. It’s why I left my synagogue,” one user wrote.

“Huge dealbreaker,” commented another.

Yet congregations that display the Israeli flag on the bimah may have different reasons for doing so.

Congregation Beth Shalom of the Woodlands in Texas explained in a June statement that the Reform synagogue displayed both American and Israeli flags “to express our gratitude and love for both countries,” quipping that, “We also love Texas, but there is not enough room on the bimah for another flag.”

In an April 2023 sermon titled “To a Non-Zionist Gen Z-er,” Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove of the Conservative Park Avenue Synagogue in New York City spoke about the Israeli flag as core to Judaism.

“Supporting Israel is, in my mind, fundamental to what it means to be a Jew today,” he said. “It is why we have the flag on the bimah, it is why we recite the prayer for Israel, it is why I am a proud Zionist, it is why I am politically engaged on behalf of Israel and why I ask that my congregants be as well.”

For Rabbi Hannah Goldstein of Temple Sinai, a Reform synagogue in Washington, D.C., the Israeli flag can have multiple meanings.

“Some of you have told us that when you see this flag, you see the flag of a modern country, a country that is responsible for the nightmare in Gaza, you see an occupation that has dragged on for 58 years,” Goldstein, who declined to comment to the Forward, said in this year’s Kol Nidre sermon. “And those are painful things to see and feel in a house of prayer.”

But for others, she said, the flag represents “the realization of a dream.”

Goldstein had sometimes “struggled to defend the place of the flag on this bimah,” she said. “But, I can’t seem to let go of the dream. Not the rose-colored, incomplete version of my youth — but a dream for what Israel might be.”