An Israeli restaurant chain said it closed due to boycotts. Protesters are celebrating.

Shouk permanently closed this month, citing ‘a toxic political climate surrounding the Israel/Gaza war’

Food at Shouk, a kosher vegan fast-casual chain in Washington, D.C., before its last two locations closed this month. Courtesy of Dennis Friedman

The owner of a vegan kosher food chain in Washington, D.C., said boycotts that targeted his business for its ties to Israel led to the permanent closure this month of his last two restaurants.

This development is the latest chapter in an ongoing wave of vandalism and boycotts aimed at Israeli and kosher restaurants, which have become frequent targets since the start of the Israel-Hamas war.

Shouk, which opened its first location in 2016, was listed on D.C. for Palestine’s “Apartheid? I Don’t Buy It” boycott initiative in March, categorized under “restaurants that culturally appropriate or sell Israeli settlement products.”

While it was unclear what effect the boycott had on the restaurant’s bottom line, organizers of the boycott happily took credit for the closure.

“LOCAL BDS WIN IN DC!!” D.C. for Palestine posted to Instagram in reference to Shouk’s closure. “In times like these, it is still important to uplift small wins, as they are glimmers of the world we want to see!”

Jinan Deena, a Palestinian chef who helped organize the boycott against Shouk, told the Forward she took issue with Shouk’s Israeli branding, viewing its omission of the cuisine’s Palestinian roots as part of a larger pattern of cultural erasure.

“This food ties us to our land,” Deena said. “As long as we continue to serve our food [and] we properly label our food as Palestinian, then we will always continue to exist.”

Shouk had tried to be sensitive to concerns like Deena’s. The restaurant once described its menu as “Tel Aviv street food,” but in recent years had shifted to marketing it as Mediterranean fare, co-founder Dennis Friedman said in an interview. The restaurants displayed the word “Shouk” in both Hebrew and Arabic — “Souk” — to signal that it was “a place for all to come,” Friedman said.

“I think more of the issue was that I’m an American Jew, and my business partner was from Israel,” he said.

Deena rejected that characterization, arguing her criticism was not about Jewish identity but cultural appropriation. “There’s a difference between Jewish and Israeli cuisine,” she said. “I’m not attacking anyone for matzo ball soup or schnitzel,” referencing two foods originating from Ashkenazi cuisine in Eastern Europe rather than Mizrahi cuisine in the Middle East.

‘Food is not owned’

Friedman and Ran Nussbacher co-founded Shouk to bring healthy, plant-based food to the Washington, D.C., area as part of a fast-casual concept.

They named the restaurant after the Hebrew word for an open-air market, and the plant-based menu was inspired by the food Nussbacher ate while growing up in Israel.

Shouk’s veggie burger earned early acclaim. The Washington Post called it their favorite in the area during the restaurant’s first year, and in 2018, the Food Network highlighted it on its series “The Best Thing I Ever Ate.”

At its peak, Shouk operated five locations across Maryland and D.C. Two of its locations closed in 2023 for unrelated reasons.

But the restaurant soon got caught up in discourse over who lays claim to foods like falafel and hummus, long the subject of contentious debate among Israeli and Palestinian chefs.

Starting in 2022, Deena, who spent her teenage years living in Ramallah in the West Bank, used her personal Instagram account to help organize a boycott of Shouk, along with other Israeli restaurants in the area. She critiqued Shouk’s description of the menu as inspired by “the open-air markets in Tel Aviv.”

“Profiting off of the occupation and oppression of my ancestors is a hard line for me, and should be for you too,” Deena wrote. “Erasure of Palestinian food is a part of the occupation strategy.”

At the time, Nussbacher dismissed such disputes as missing the larger purpose of food.

“I’m disappointed when we don’t use food as a bridge,” Nussbacher told Moment Magazine in 2022. “Is pizza an appropriation of Italian culture? Is pasta Italian or Chinese? Food is not owned. Food is dynamic. And it’s created and recreated time and again. The question of ownership is irrelevant.”

The boycott gains traction

Shouk was “on track toward profitability” at the start of this year, the restaurant said in an email to customers about its closure.

Sales declined dramatically this summer, Shouk said in the email, more than the typical seasonal decline.

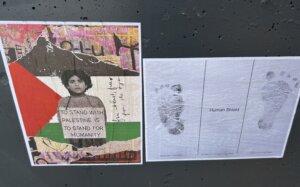

Friedman, who did not share specifics about the business’ financials, attributed the downturn to protesters chanting “Free Palestine” outside the restaurant, gluing posters to the restaurant’s windows and outdoor seating, and coming inside to intimidate customers and staff.

At Shouk’s Georgetown location, which closed in 2024, protesters were “steady and frequent, and they just didn’t let up,” Friedman said.

“We heard from customers that there was some concern. It was either concern for safety or just not wanting to deal with that negativity in that type of environment,” Friedman said. “And I couldn’t blame them. I wouldn’t want to, either.”

Friedman said he was in touch with authorities about the incidents, and a plainclothes officer began monitoring the situation from a car across the street. But he said the extra security ultimately didn’t make a difference.

On Oct. 3, Shouk emailed customers explaining why the remaining two restaurants in Rockville, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., had closed.

“One factor was that we found ourselves caught in the crosscurrents of a toxic political climate surrounding the Israel/Gaza war,” Shouk wrote. “More and more, customers have chosen to avoid businesses connected to Israel. We heard from long-time regulars who stopped visiting us for these reasons.”

“The restaurant business is a hard business to begin with, with razor thin margins,” Friedman told the Forward. “And so if you have something like this, and it’s prolonged, it’s kind of inevitable what’s going to happen.”

Friedman emphasized that Shouk was “not a political place.” To the extent that the restaurant did engage in advocacy, Friedman said, it was focused on environmental issues, from promoting plant-based eating to using biodegradable cutlery.

“We wanted to truly do something that could be a game changer. And for quite a while it was — so that’s why it makes it a little heartbreaking that we had to stop,” he said. “Even though I’m sad of how it ended, man, I’m grateful for the last 12 years.”