Stanley Fischer — Born in Africa, Served in Israel — Named to Federal Reserve

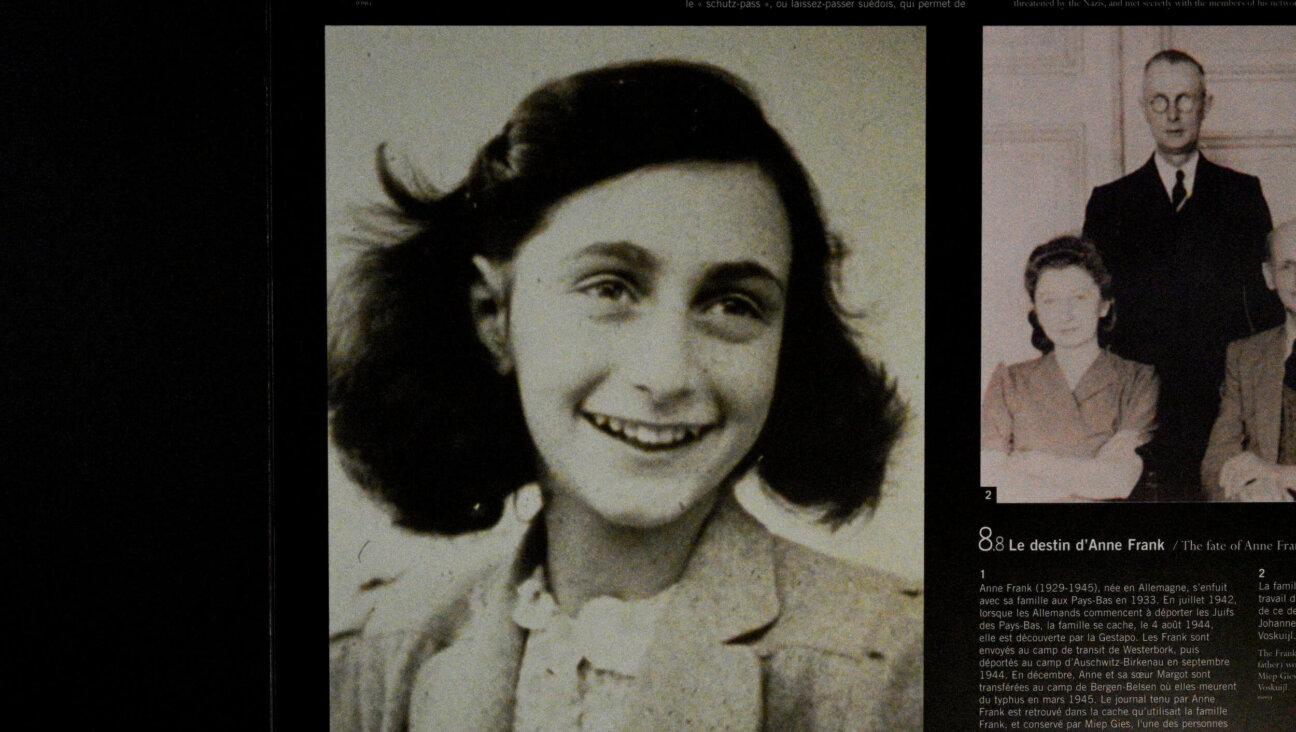

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Armed with an unusual biography and international respect as a leading economist, Stanley Fischer, an Israeli-American dual national, is poised to take his place as vice chairman of the Federal Reserve System, the body that effectively controls America’s money supply.

Fischer’s nomination by President Obama is a first of sorts. Up until last year, Fischer was serving as head of the Bank of Israel, more or less the Fed’s counterpart institution in the Jewish state. But apart from complaints from some traditionally harsh critics of Israel, who argued that his role in Israel makes his prospective new role on the Fed incompatible with American interests, Fischer’s assumption of his new post has drawn nothing but praise.

Alan Blinder, who served as vice chairman of the Fed’s Board of Governors during the Clinton administration, typified the mainstream response to the now all-but-sure prospect of Fischer’s appointment.

“He is a very fine economist who has distinguished himself in several dimensions,” said Blinder, a renowned economics professor at Princeton University. “He wasn’t born in America, and he has a lot of international experience, but he is an American economist.”

Responding to Fischer’s critics, Blinder said: “There’s no conflict. What the Bank of Israel does has minimal implication for other countries.”

The Senate Banking Committee confirmed Fischer’s appointment to the Fed’s Board of Governors on May 21. Fischer still awaits a separate vote approving his post as vice chairman, but given the two-thirds majority of senators that backed his board membership, confirmation as No. 2 at the Fed is guaranteed.

An acclaimed banker and economist, Fischer comes to the position with a breadth of international experience. He was born to a Jewish-Zionist family in what is now Zambia, grew up in Zimbabwe, spent six months on a kibbutz in Israel, then settled in the United States for four decades before immigrating to Israel upon being invited by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to serve as governor of the Bank of Israel.

Fischer’s ties with Israel date back to his childhood in Southern Rhodesia, which is now Zimbabwe. He was a member of the Zionist-socialist Habonim youth movement, with which he visited Israel in 1960. He later came back and studied Hebrew at Kibbutz Maagan Michael, on the Mediterranean coast. But it would take another four decades before Fischer would return to Israel to settle down in Jerusalem, at least temporarily.

In the intervening years, Fischer built a career as a leading economist. As a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he wrote textbooks on macroeconomics. In the public sector he served as chief economist of the World Bank and later as deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund. Fischer won praise in this capacity for helping the Mexican economy recover from its financial crisis. In between, he served as vice chairman of Citigroup; it was a lucrative banking position that has brought his personal wealth to between $14 and $56 million, according to his disclosure before his congressional confirmation hearing.

In 2005, Fischer was handpicked to head Israel’s central bank. Netanyahu, who served as finance minister in Ariel Sharon’s government at the time, and Ron Dermer, then Netanyahu’s adviser and now Israel’s ambassador to Washington, convinced Sharon that Fischer, with his international credentials, could bring to the position the worldview and experience that local Israelis lacked. Fischer agreed to leave behind his high-paying positions in the United States and immigrate to Israel. Upon taking the post, he became an Israeli citizen but did not renounce his American citizenship, as other high-ranking Israeli officials, including Dermer, were required to do.

Fischer quickly won over the Israeli public — first with his surprising command of Hebrew and later as economic skies darkened over Europe and the United States — with a policy that kept Israel safe as world economies collapsed.

Answering questions from senators during his March 13 Senate Banking Committee confirmation hearing, Fischer reflected on his experience leading Israel’s central bank through the crisis. “Israel was lucky, or whatever, that it didn’t have a financial crisis,” he said, “so when we reduced interest rates, the banks could lend more and they did, and Israel escaped the main burden of the crisis.”

In 2010, as Israelis breathed a sigh of relief over having survived the financial storm unscathed, Fischer was sworn in for a second five-year term. But he did not complete the term, and in 2013 he decided to step down and return to the United States.

While most in Israel and the world deemed his term successful, Fischer also had some harsh critics who disapproved of his financial leadership. Avi Tiomkin, venture capitalist and adviser to international hedge funds, voiced this criticism in Israeli financial publications, accusing Fischer of leaving “scorched earth” behind him and of strengthening the Israeli currency in a way that weakened its economy. “No wonder Fischer wants to go back to the United States — he understands very well the magnitude of the crisis about to come and understands that this will make him the next Alan Greenspan,” Tiomkin wrote, referring to the former Fed chair whom many blame for not anticipating the 2008 crisis.

The Fed wasn’t Fischer’s first choice after leaving his post in Israel. Fischer initially aimed for the position of managing director of the International Monetary Fund after the departure of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, but, now 70, he could not qualify, since the organization requires that its managing director be 65 or younger.

The Fed, however, was a natural second choice. Fischer was a mentor for former Fed chair Ben Bernanke and is also close to current chair Janet Yellen, who chose him for the position.

Fischer’s economic philosophy as central banker fits well with that of Yellen. He noted during his hearing in Congress the need to keep on working to reduce unemployment. “Slow growth is not an abstraction,” he said, “slow growth is people not finding jobs.”

This philosophy could be tested within months, when experts predict that debates within the Fed’s board of governors will break into public view. Some governors are calling for new moves to stimulate the economy, and others demand a focus on an exit strategy that will end the Fed’s low-interest policy and the monthly purchase of financial assets known as quantitative easing.

“Stan Fischer is walking into that kind of division,” said Blinder, who noted that in this debate, Fischer is likely to be a “reliable vote” on Yellen’s side.

Contact Nathan Guttman at [email protected] or on Twitter, @nathanguttman