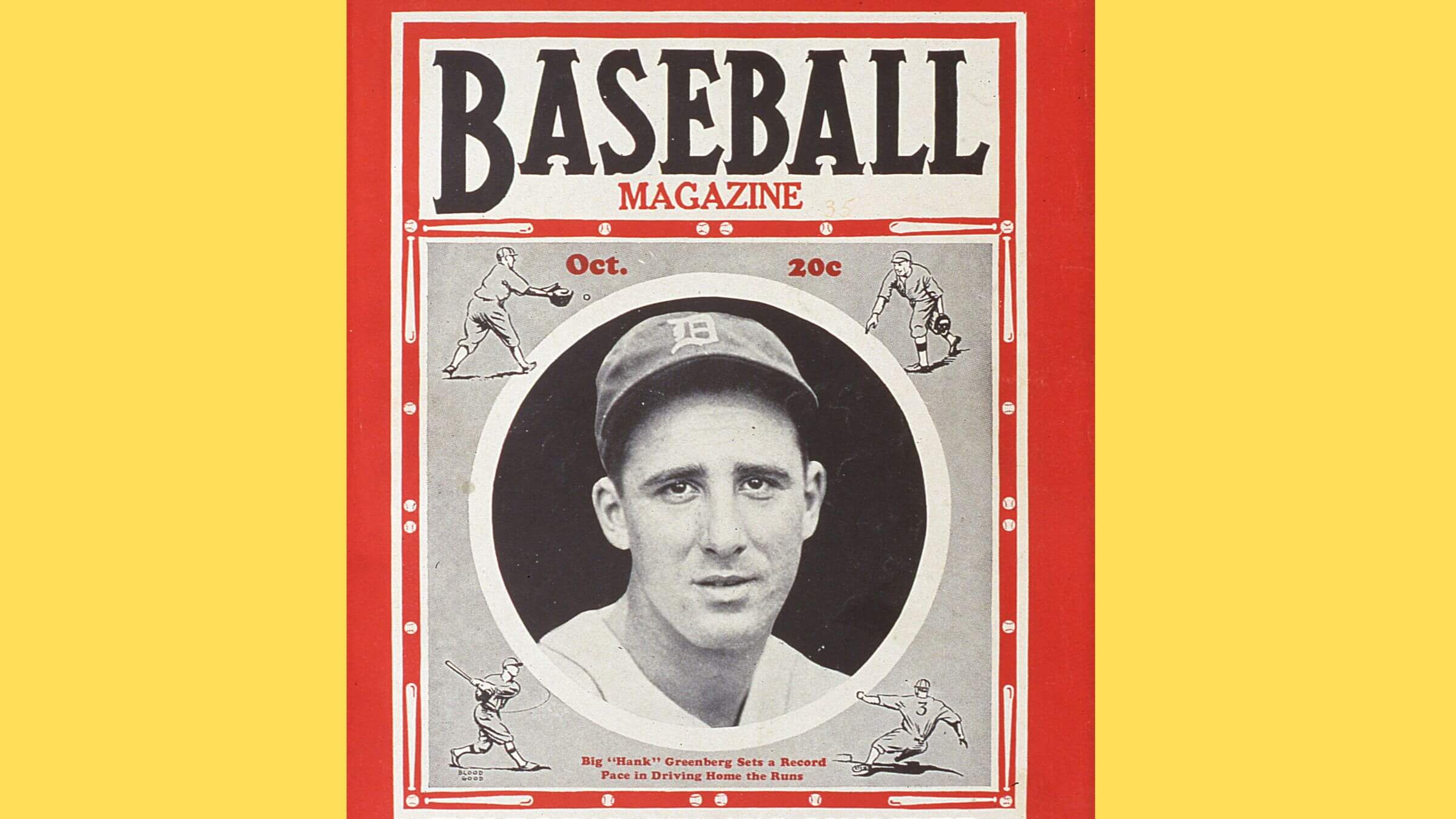

Back from war, Hank Greenberg took a hard swing for the pennant

In the midst of the 2022 pennant races, a look back at a particularly compelling one in 1945

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Contending baseball teams often make midseason trades to improve for the pennant race. But in the summer of 1945, the Detroit Tigers made a move that drastically improved their roster without having to give up any players in return, welcoming back slugger Hank Greenberg after he served 4 ½ years in the military during World War II.

Greenberg, a future Hall of Famer, had been the best Jewish player of his generation and one of the biggest stars in the sport. In 1933, his rookie season, “there were Jewish baseball players that had made it to the majors, but there had never been a Jewish baseball star,” wrote Joe Posnanski in The Athletic. “In truth, there had never been a Jewish-American sports superstar at all.”

Greenberg soon changed that. In 1935, he won the American League MVP, leading the Tigers to a World Series title. In 1938, he nearly matched Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record of 60, swatting 58. And in 1940, the year before he enlisted, he led the Tigers to the American League pennant with another monster season, pacing the league with 41 homers, 50 doubles and 150 RBIs, while batting .340 and winning the MVP again.

But he was 29 in 1940, in his prime. The Sporting News, known as the “Bible of Baseball” back when baseball reigned as the nation’s supreme sport, was among the doubters as Hammerin’ Hank prepared for his July 1, 1945, return at Briggs Stadium in Detroit.

“Nearly five seasons have elapsed,” the publication observed. “Greenberg now is 34 years of age. Quite obviously he is not in possession of the physical qualities which made him the highest salaried ball player of 1941. Perhaps, while in the service, Hank became rusty in the game.”

But 26-year-old Ted Williams, who was finishing up his third and final year of wartime service, had a different take. “Greenberg will hit, and you can count on that,” he said. “At the end of the season, he’ll be the most dangerous hitter on the Detroit team.”

Enlisting — and enlisting again

Greenberg had actually enlisted twice in 1941. He was drafted into the service on May 7, the first baseball star to enter the military, a day after hitting his first two home runs of the season in a victory over the New York Yankees. They would turn out to be Greenberg’s only homers that year, as he missed the rest of the season serving in the military. Newsreel cameras and photographers documented his induction while a 13-piece WPA orchestra played swing music, according to Greenberg biographer John Rosengren.

Greenberg was honorably discharged in December. Two days later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and he joined the Army Air Corps — the first pro baseball player to re-enlist.

“This doubtless means I am finished with baseball, and it would be silly for me to say I do not leave it without a pang,” he said. “But all of us are confronted with a terrible task — the defense of our country and the fight of our lives.”

“The decision announced last week by Hank Greenberg gave the game and the nation a special thrill,” wrote longtime Sporting News publisher J.G. Taylor Spink, on Dec. 18, 1941. “Fans of America, and all baseball, salute him for that decision.”

Greenberg served in the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations, flying B-29 bomber missions, returning home with the Presidential Unit Citation and four battle stars. He rejoined the Tigers in mid-June 1945.

“His return reversed the question that had affected every team throughout the war,” wrote Bill Gilbert in “The Seasons,” a book about 10 memorable seasons in baseball, starting with 1945. “Instead of wondering which teams would be the most affected by the military draft, the question became which teams would be helped most by players returning from military duty.”

Before seeing game action, Greenberg worked to get himself into playing shape.

“After 10 days or two weeks, I’ll have a lot better idea than I have now of how much or how little I can help the club,” he said. “I believe it will be a matter of timing. I know I need plenty of batting practice.”

When he made his 1945 debut on July 1, the Tigers were in first place, 1 ½ games ahead of the second-place New York Yankees. The Tigers hosted the last-place Philadelphia Athletics in a doubleheader that afternoon in front of a season-high crowd of nearly 48,000. In the first game, Greenberg started in left field and batted cleanup, going hitless in his first three at-bats and drawing a walk in his fourth turn. Then in the bottom of the eighth inning, he hit a home run over the left field wall, earning a standing ovation. The Tigers won 9-5.

The New York Times featured a prominent photo of Greenberg crossing home plate with a teammate waiting to congratulate him, with the caption headlined: “A glad hand was out in Detroit for an old hand.”

A heroic hit for the pennant

Over the season’s final three months, Greenberg helped carry the team down the stretch by hitting .311 with 13 home runs and 60 RBIs in just 78 games. He finished 14th in the MVP vote — a remarkable feat for a player who missed half the season. Detroit soon pulled away from the Yankees, but they wound up having to fight off a surprising challenge from another team, the Washington Senators, who usually roamed at the bottom of the American League standings.

The exciting pennant race came down to the final day of the season. The Senators had already finished their schedule, and the Tigers were scheduled to play a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns, the defending AL champs. Detroit needed just one win to clinch the pennant. A Browns sweep, on the other hand, would set up a one-game playoff between the Tigers and Senators in D.C. to determine the pennant winner.

After eight innings of the first game, the Browns led 3-2, on a rainy afternoon in St. Louis. Greenberg came up with the bases loaded in the top of the ninth inning. He smashed a line drive down the left field line. As he recalled in his autobiography:

“I stood at the plate and watched the ball for fear the umpire would call it foul. It landed a few feet inside the foul pole for a grand slam. We won the game, and the pennant, and all the players charged the field when I reached home plate and they pounded me on the back and carried on like I was a hero. There was almost nobody in the stands to pay attention, and there were few newspapermen. Just the ballplayers giving me a hero’s welcome.”

“Never was a title won in more dramatic fashion, before,” The Associated Press declared. “Premature darkness was settling over the field and a light mist was falling as big Hank stepped up with his team a run behind …”

Utility infielder Eddie Borom was especially excited. The AP reported that he “leaped around Greenberg’s neck and planted a kiss on his check at home plate.”

The team returned to Detroit and a welcoming party of thousands of fans at the train station.

Greenberg continued his hot hand in the World Series, hitting .304 with two homers and three doubles, as the Tigers beat the Chicago Cubs in seven games. (That would be the Cubs’ last trip to the World Series until 2016.) The next year, he proved his shortened 1945 season was no fluke: leading the league with 44 home runs and 127 RBIs, in what turned out to be his last season with Detroit. He retired a year later after a single season with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In 1956, Greenberg became the first Jewish baseball player elected to the Hall of Fame.

In his autobiography, Greenberg, who died in 1986, said he took a special satisfaction at knocking out the Washington Senators after returning home from the war.

“The best part of that home run,” he recalled, “was hearing later what the Washington players said: ‘Goddam that dirty Jew bastard, he beat us again.’ They were calling me all kinds of names behind my back, and now they had to pack up and go home, while we were going to the World Series.”