‘A simple shared love’: A Jewish sportswriter pays tribute to his immigrant father’s baseball dreams

Veteran sportswriter Jerry Izenberg’s book about his Lithuania-born father and growing up Jewish in Newark will publish on May 1

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

For many Jewish immigrants to the United States at the turn of the 20th century, baseball helped make them feel like Americans. Longtime New Jersey Star-Ledger sports columnist Jerry Izenberg writes movingly in his new memoir about one such immigrant — his father.

Harry Izenberg arrived in New Jersey in 1882 as an 8-year-old from Lithuania, speaking no English, and other kids made fun of him and the clothes he wore. Then he hit a baseball into orbit in fourth grade, and for the first time in his life felt like he was where he wanted to be.

Harry dropped out of school that year to help support his widowed mother and his siblings. Later he would be wounded in World War I, but that didn’t make him an American in his mind, Harry told his son, Jerry, in a conversation captured in the book.

“I still think I became an American back on that day in the little park in Paterson the first time I hit a baseball,” Harry said. “That made your old man as much an American as any kid in the school. That’s when I fell in love with this country and with the game. And I will love both of them the rest of my life.”

Harry would go on to become a minor-league player, often the only Jew on his team or even the entire league, sometimes ducking beanballs thrown by antisemitic pitchers.

“I think his approach to Judaism was shaped during his baseball years,” Jerry Izenberg writes in the memoir, Baseball, Nazis & Nedick’s Hot Dogs: Growing Up Jewish in the 1930s in Newark, which is being released May 1. “It was far more cultural than it was ritualistic. During those years in ‘the enemy camp,’ he had to defend his religion more than practice it.”

The memoir is as much about his father, who died in 1958, as about him. It captures the experience of two generations of Jewish Americans — the immigrant and the first native-born — and how each embraced America’s opportunities and faced its prejudices.

Newspaperman

In an interview this week, Jerry Izenberg, 92, said he never heard racial or ethnic slurs uttered in his house as a boy.

“And I asked my father about it one day,” Izenberg recalled. “And he said, ‘Let me tell you something. I ducked so many balls thrown at my head that you’ll never hear those words in this house because we’re all in the same boat.’ That’s pretty good for a fourth-grade dropout.”

In 1952, 70 years after his father emigrated to the U.S., Jerry Izenberg was a student at Rutgers University, discussing his future with a history professor he respected, Henry Blumenthal. Izenberg said he wanted to take the Foreign Service exam, but Blumenthal warned him that as a Jew, he’d be marginalized:

“You will always be a minor functionary. The posts to Europe in our diplomatic corps are reserved for the privileged — graduates of Yale and Harvard and Princeton, not for young men like you who earned their degrees in a building that once housed a brewery. At least if you remain a sportswriter, nobody will keep you from covering the World Series because of your religion.”

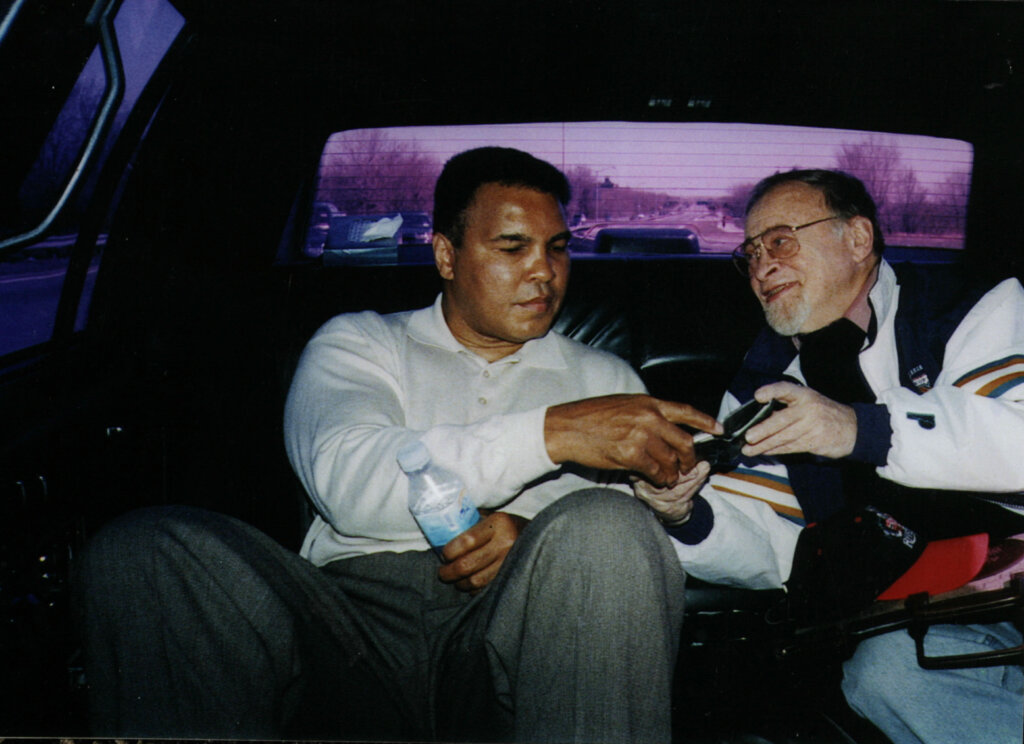

It turned out to be good advice. Izenberg would go on to cover not just the World Series, but the first 53 Super Bowls, 54 consecutive Kentucky Derby races, and many Muhammad Ali fights, starting with the 1960 Olympics, when the boxer was still known as Cassius Clay. Izenberg is also the author of books including Once There Were Giants: The Golden Age of Heavyweight Boxing; No Medals For Trying: A Week in the Life of a Pro Football Team; and Rozelle: A Biography.

In 2020, at the age of 90, he had his first novel published, After the Fire: Love and Hate in the Ashes of 1967. It’s the story of a forbidden relationship between a Black young woman and an Italian American high school football star and war hero in 1960s Newark.

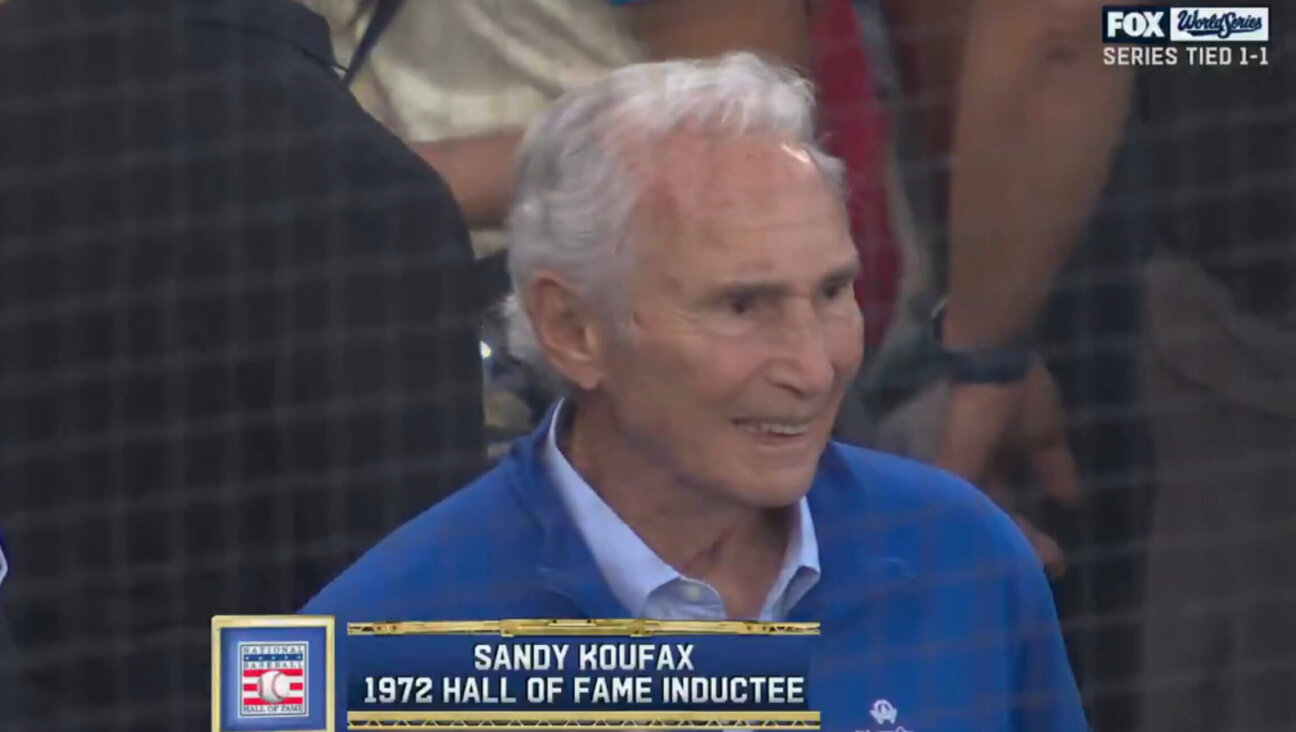

Izenberg won the Red Smith Award in 2000, presented every year by the Associated Press Sports Editors to a writer or editor who has made major contributions to sports journalism. Currently columnist emeritus at the Star-Ledger, Izenberg has been inducted into 17 Halls of Fame, including the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

Izenberg, who lives in Henderson, Nevada, quipped in the interview that he decided to write the memoir because “I’m getting old.”

“I have tried much of my life to honor my father because I really respect what he overcame and what he did,” Izenberg said. “If the book has a subtext, it’s my relationship with my father.” He writes about his father’s passionate rooting for the New York Giants, and the abuse he’d inflict on his Philco radio when the team let him down — as it often did during the 1940s.

In one of the book’s best scenes, Izenberg describes having a baseball catch with his dad on a snowy December day, neither one wearing a coat, as his mother bangs on the window and yells, “Get in the house! Meshuge. Meshuge. You are both crazy – you will catch pneumonia!” Father and son laughed and pretended they couldn’t hear her. “We continued to play, my mother continued to scream, and the snow continued to fall.”

“He had given me a lifetime gift — a simple game and a simple shared love for it,” Izenberg writes. “It remains there, bright and shining in memory eighty-three years later. In the soul of my memory, I see our kind of shared love of baseball again. It never fades.”

Ballplayers and boxers

As a kid growing up in the Great Depression, Izenberg said in the interview, the most important classroom he experienced was watching his parents and his older sister survive the economic hardship of that era.

Izenberg describes his mother, Sadye, as loving but overbearing, who years later became upset with Jerry when he dated a non-Jewish woman (whom he would later marry — and divorce).

“Her reluctance was compounded by a dark cloud of ethnic antecedents: the Polish-American Catholic and the Lithuanian-American Jew,” Izenberg writes. “‘No good can come of this,’ she said. ‘Her people killed Jews in Poland and Lithuania.’ Actually, that would have been difficult, since for two generations they had all lived in Kearny, New Jersey. ‘College kids,’ she warned, “think they know everything. You better think it over, mister.’”

Izenberg, who was born in 1930, came of age as the Nazis took power — and some American Nazis flexed their muscles in the United States. He writes of going to the Newsreel Theatre in downtown Newark and watching footage of the infamous 1939 German American Bund rally in Madison Square Garden, which attracted 20,000 people, some of whom carried posters that said, “Stop Jewish Domination of Christian America.” The spectacle featured a giant portrait of George Washington flanked by two large swastikas.

“Back on the street,” Izenberg writes, “my old man said something I never forgot: ‘That wasn’t Berlin. That was New York. They’re not an ocean away. They are here. But this is America, pal. We are Americans and we are Jewish and we will stop this crap.’

“Then he looked down at me and said, ‘Nedick’s hot dog?”

“Yeah, yeah, with an orange drink. OK?”

“You bet. You bet.”

In the interview, Izenberg recalled seeing kids in Hitler Youth suits at German American Bund camps in New Jersey.

But American Jews also had something to celebrate in the late 1930s — the 1938 “Summer of Hank Greenberg,” as Izenberg calls it in the book, when the Detroit Tigers’ Jewish slugger challenged Babe Ruth’s single-season home record.

“In my house, we kept score,” he writes. “My father talked about what Greenberg had to do to make history. My mother did all but set a place for him at the supper table. My sister didn’t much care, and it was my job to bring the little Philco radio in from the front porch each evening and turn on WOR for the Stan Lomax Sports Report.” Greenberg came up two homers short of Ruth’s record 60 (since broken).

Another sports memory from that year is the famous match between African American boxer Joe Louis and German fighter Max Schmeling, who had knocked out Louis in 1936. Leading up to the 1938 rematch, the Nazis touted Schmeling as a member of the superior “Aryan” race. Izenberg’s father insisted that Izenberg and his sister stay up to listen to the fight, over their mother’s protestations that it was a school night.

“This is a more important lesson for them,” Izenberg’s father retorted. “Joe Louis is a colored man. He is fighting for all the colored people in this country. More than that, he is fighting for us Jews, because Schmeling is representing Hitler.”

Izenberg writes that his father was wrong — Schmeling was not a Nazi. Izenberg in fact would befriend him years later.

Louis knocked out Schmeling in the first round. Twenty-five years later, Izenberg reminisced about a talk he had with a Black man about the fight.

“I never met your daddy,” the man told Izenberg, “but on that night we were brothers under the skin.”