This baseball star’s life paralleled Jackie Robinson’s — this Jewish sportswriter wants to make sure he’s not forgotten

Jerry Izenberg has made it his crusade to honor Hall of Famer Larry Doby

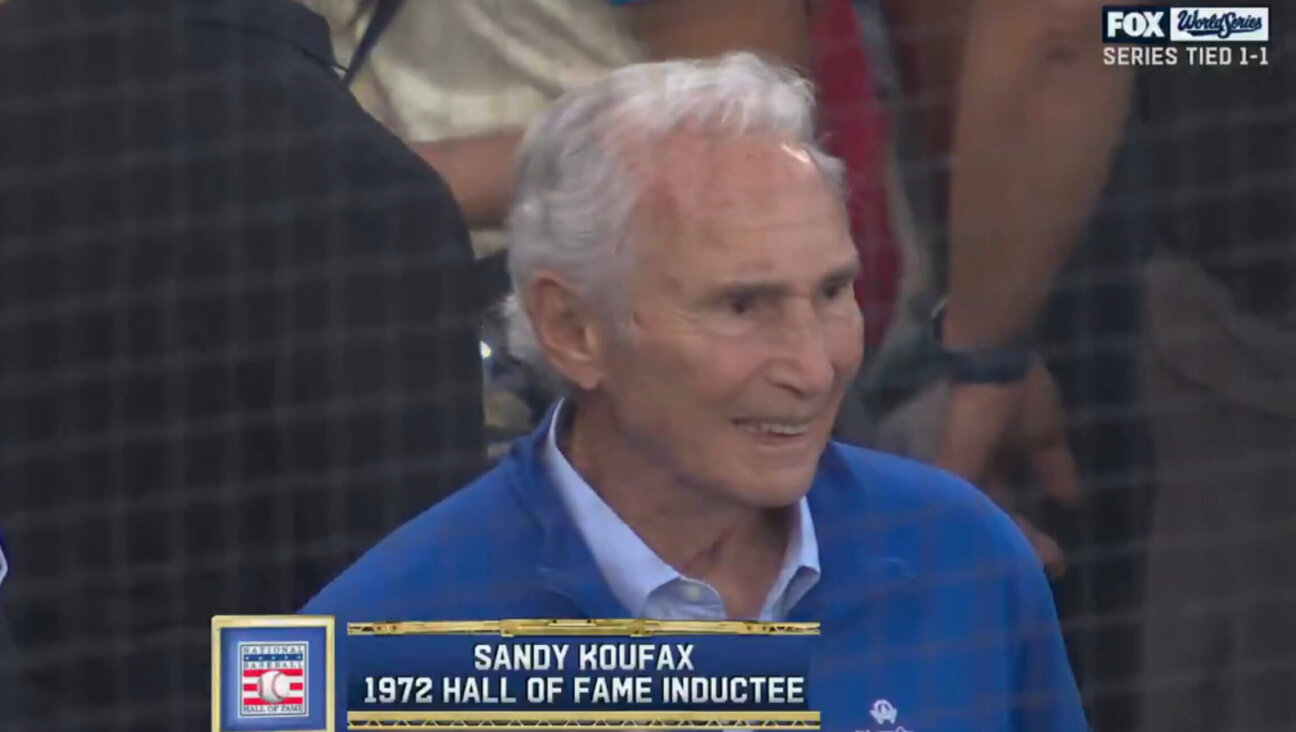

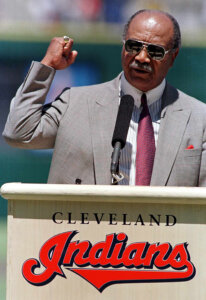

Larry Doby plays for the White Sox during a 1956 spring training game. Photo by Getty Images

Every year since 2004, Major League Baseball has celebrated Jackie Robinson Day, which pays tribute to the life and legacy of the first African American ballplayer to break MLB’s color barrier. The event observes the anniversary of Robinson’s April 15, 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and mandates the wearing of Robinson’s retired uniform number (42) by all players in that day’s scheduled MLB games.

It’s a milestone well worthy of commemoration, of course, though the reason that no African Americans played for major league teams until 1947 — institutionalized racism — is rarely called out during the celebrations; ditto for the numerous challenges and indignities suffered by the Black players who followed in Jackie Robinson’s wake.

Players like Larry Doby, who became the American League’s first African American player on July 5, 1947 when he stepped to the plate for the Cleveland Indians in the second game of a doubleheader against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. Doby had to endure the same dehumanizing treatment from opponents, baseball fans and sportswriters that Robinson did, all while playing in an even less welcoming setting. Coming straight to the Indians from the Negro National League (the Indians’ maverick owner Bill Veeck had purchased his contract from the Newark Eagles), Doby found himself on a team whose manager didn’t want to play him and whose players were largely unhappy about his arrival, in a city where racial segregation was still very much a fact of life.

Nonetheless, Doby stuck it out and — after switching from infield to outfield at the beginning of the 1948 season — quickly transformed himself into one of the era’s great ballplayers. Doby led Cleveland to a World Series championship that year, becoming the first Black player to hit a home run in the Fall Classic. Four years later, he became the first Black player to win a home run crown in either league, a feat he repeated in 1954 when Cleveland once again won the AL pennant. Doby also made the American League All-Star team seven straight times.

And yet, despite his excellence as a player and the hardships and abuse he overcame on the way to a brilliant career, Larry Doby’s legacy has been vastly overshadowed by Jackie Robinson’s. The anniversary of Doby’s breaking of the American League color barrier is officially celebrated only in Cleveland; and while Robinson became a first-ballot Hall of Famer in 1962, Doby had been retired as a player for nearly 40 years before he was finally inducted into Cooperstown.

“He was ignored by many in the game to which he gave so much,” writes Jerry Izenberg in his new book Larry Doby in Black and White: The Story of a Baseball Pioneer. “Out of sight became out of mind for the memories he should have generated. For far too long he was relegated to a position in the collective minds of the nation that didn’t equate to an enduring shelf life and wasn’t worth much. He had integrated the entire American League, but the feeling was, ‘Well, wasn’t Jackie Robinson number one? Didn’t Jackie end the color line?’ And as good a player as Doby was, ‘not being number one’ was and is a typical American slight. In America, number two is just a number.”

Izenberg, a legendary sportswriter who has been enshrined in 16 different halls of fame himself — including the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2016 — was a dear friend of Doby’s for decades, and Larry Doby in Black and White is a heartfelt testament to that friendship, as well as a reminder of both Doby’s considerable talents and the considerable obstacles faced by so many great Black ballplayers, even after the “color line” was ostensibly shattered.

Izenberg angrily recounts not just the institutionalized racism that they came up against, but also the blatantly racist behavior of baseball figures like commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, New York Yankees general manager George Weiss, Washington Senators/Minnesota Twins owner Calvin Griffith, and Cleveland sportswriters Gordon Cobbledick and Franklin Lewis. The latter two often wrote pieces criticizing Doby for being “moody” and “surly,” while making no attempt to understand why a man who had been cold-shouldered by many of his white teammates might be somewhat less than sunshine and rainbows in the clubhouse.

Off the field, however, Doby seems to have been a kind, loyal and generous man who was deeply loved by those he allowed to get close to him, Izenberg included. Growing up poor in a largely Jewish neighborhood in Paterson, New Jersey — where he often earned some spare change by serving as a Shabbos Goy — Doby formed a lifelong bond with Joe Taub, the son of Polish Jewish immigrants.

After Doby’s retirement from baseball, he worked with and for Taub in several different capacities, including as community relations director for the New Jersey Nets, which Taub co-owned in the 1970s and 80s. “Everyone was shrewd and looking for an angle,” Taub told Izenberg of the Carroll Street neighborhood where he and Doby first met as kids. “There was a hidden instinct you develop on this street. We knew we couldn’t con each other. So we were honest. We trusted each other.”

I recently spoke with Jerry Izenberg about Larry Doby in Black and White.

What made you want to write a book about Larry Doby?

Doby and I were very close. I think I really wrote it because as Doby got older, and got snubbed more and more, I got madder and madder.

One of my favorite stories in the book is about the Hall of Fame. He thought that I got him in there, but I don’t think so; I think I played a role. I wrote many times that he should be in the Hall, and he came to me and said, “I’m never gonna get in, and I don’t want you to embarrass yourself; stop writing that I should be in.” I said, “You know, I think I’ll take one more shot.” He said, “Be diplomatic!” I said, “You’re telling me to be diplomatic?”

So I wrote this piece which began, “Why am I not surprised that the members of the Veterans Committee will not put Larry Doby in the Hall of Fame where he belongs? Many of them were the same sons of bitches that didn’t want him to come to bat once.” I photocopied it, and I mailed it to everybody on the committee, and I got one answer. It said, “Dear Asshole: Monte Irvin, Yogi and I have been trying to get him in for years. So get off your fat ass, get off your couch, and help us get the votes we need to do it — Ted Williams.” [laughs]

Was Ted Williams always on Doby’s side?

Oh yeah. When Larry was made into an outfielder [at the beginning of his second season in the majors], those were the days where the players used to leave their gloves on the outfield grass. Larry’s going out to play center field against the Red Sox one day, and as he bends over to pick up his glove, somebody swats him on the ass. He turns around and it’s Ted Williams; and Ted says to him, “Keep your chin up, Rook; you’re gonna be a great one, one day.”

When did you first become aware of Larry Doby?

I became aware of him when he played for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. The Newark Eagles only won one championship, in 1946, but they had great, great players — guys like Larry Doby, Monte Irvin and Leon Day. When I was a snotty kid in about the sixth or seventh grade, I learned how to sneak into Ruppert Stadium, which was the home of the Newark Bears, the greatest franchise in the history of minor league baseball. But when they went on the road, the Eagles rented the place and played there, and they had a big constituency.

So I’m in there at Ruppert Stadium one day, and there’s a team I don’t recognize; they’ve got a script “E” on their hats, and it says “Eagles” across the chest. And I said to some Black guy who was standing there, “Who are these guys? Why are they in my park? Why isn’t my team here?” He said to me, “They’re the Newark Eagles, and they’re very good.” So that’s when I started sneaking in to see Newark Eagles games. Newark was a predominantly white town then, but many days I was the only white kid in short pants in that ballpark, and those fans treated me royally; they bought me ice cream, they knew my name. They couldn’t believe that I was coming to see the Eagles play.

Larry had been a Negro Leagues star, and his first roommate in the majors was Satchel Paige, the legendary Negro Leagues pitcher. But it doesn’t sound from your book like they had much else in common.

People would think that he and Satchel Paige would be a natural fit. But he didn’t like Satchel Paige at all, and he had a good reason, I feel. The radio show that Doby hated the most was Amos ‘n’ Andy — he hated it. And Satchel was a living advocate for it. Because he’d tell all these stories where he was dumb and stupid and whatever else, and the players would roar, and that’s what he wanted. And Doby explained to me, “I didn’t like it. I didn’t like him. I respected him as a pitcher; he’s gotta be one of the greatest who ever lived, by far. But he didn’t understand — they weren’t laughing with him, they were laughing at him. And we don’t need any more of that.”

On the other hand, Joe Gordon, the Indians’ veteran second baseman, was one of the few white players on the team who went out of his way to befriend Larry.

When Larry reported to the team, five guys firmly shook his hand, two guys turned and faced the wall, and the other guys give him the “dead fish” handshake. Joe Gordon was the first guy to run and shake his hand, which pleased me because Joe Gordon was my boyhood hero when he played second base for the Yankees; he shook his hand, hugged him and said, “We need more power on this team!”

=When they all went out onto the field to warm up, all the other guys were deliberately ignoring Larry and refusing to throw him the ball; he was about to say, “The hell with this, I’ll go home,” but then Joe Gordon elbowed him in the ribs and said, “You want to go out and warm up, or you want to stand here and profile your beautiful new uniform?” They went out and threw the ball to each other, and for the rest of the time they were on the team together, they never warmed up with anybody else. Gordon was Larry’s best friend on the team; he had a few others, but not many.

Do you think Larry’s career would have been different — or that his legacy would be viewed differently — if he’d played for a New York team instead of a team in Cleveland?

Well, as you may remember, the name of the first chapter in my book is “Cleveland Ain’t Brooklyn”. Cleveland was a segregated town — segregated schools, segregated hospitals, and an amusement park that you didn’t dare set foot in if you were Black. And he was the only Black player in the league in 1947, and oh what he went through…

A lot of people thought Larry was jealous of Jackie Robinson, that Jackie got all the credit [for integrating major league baseball]. But he said to me, “Hey, Jackie was the first. He was the first to take the crap. He was the first to get it all year long. He deserves all the credit he gets. But you know, Jerry, nobody said, ‘We’re gonna be nice to the second Negro that comes along.’” And they were not.

What’s your opinion of the recent decision to merge Negro Leagues statistics with the official MLB ones?

It’s a good question, and it’s the right question. My statement on that is simple: It’s a great thing.