Orthodox Jews navigate a World Series quandary: How to watch the games

It’s Yankees vs. Dodgers vs. Shabbat for Jews who observe

A fan poses for photos next to a replica of the World Series trophy at Dodger Stadium. Photo by Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

His beloved New York Yankees are in the World Series for the first time since he was 7. But 22-year-old Max Mannis has a problem: He’s an Orthodox Jew, and Game 1 is on a Friday night.

During the regular season, Mannis watches just about every game that doesn’t fall on Shabbat; the ones that do, he misses without giving it much thought.

But this is the World Series. And it’s not just the Yankees — it’s the Yankees versus the Los Angeles Dodgers. So Mannis, who creates baseball content for a living, is working on a plan.

For millions of baseball fans, this year’s matchup of the Los Angeles Dodgers and the New York Yankees — arguably the sport’s two most storied franchises — is a dream decades in the making. But for a small number of them, the World Series schedule reads like a cruel joke: Up to four games of the best-of-seven series — the first two and, if played, the last two — overlap with the Jewish day of rest in parts of the U.S.

While the World Series has opened on a Friday for the last three years, never has the schedule affected more Sabbath-observant fans than this fall, when the cities facing off are home to the two largest Orthodox communities in the United States. So Jewish fans who have waited their whole lives to see the Bronx Bombers take on the Boys in Blue are girding themselves to miss a chunk of the showdown — or, like Mannis, looking for loopholes in Jewish law so they won’t have to.

Crucially, the laws of Sabbath prohibit operating electronics, but they don’t forbid using a light — or, say, a television — that’s been turned on by someone else. Mannis thinks it’s possible his less-observant friends will catch a hint Friday and take the remote into their own hands. But he won’t say he “hopes” they do — it would be straying too close to an ask, which would again be a violation.

“Whatever Hashem has planned for that is how that will go,” he said, using a name for God.

For years, the World Series opened on Tuesday, which meant Games 3 and 4 fell on Friday and Saturday — not ideal for Orthodox fans, but preferable to what came next. In 2022, seeking to expand the number of playoff teams, Major League Baseball changed the Wild Card round from one game to a best-of-three series, delaying the rest of the playoffs and usually giving the World Series a Friday start.

That all games begin at 8:07 p.m. ET makes the schedule especially rough for Orthodox fans in L.A., for whom all four home games coincide with Shabbat. They are set to miss all of Friday’s Game 1, which begins during the holiday of Simchat Torah and would conclude on Shabbat; lots of Game 2, which will begin roughly 90 minutes before Shabbat ends; all but the first couple innings of Game 6 the following Friday; and perhaps the first half of Saturday’s Game 7. (Because of the time difference, Games 2 and 7 don’t begin until after Shabbat ends in New York.)

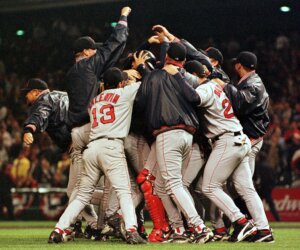

“If Game 6 is the last game, that’ll be rough,” said Julie Fax, a writer and lifelong Dodgers fan. “You want to be watching when your team does the circle jump on the mound.”

One nice thing about the Dodgers’ 12 consecutive playoff appearances is that Orthodox fans like Fax have grown used to missing big games in October. She’s accustomed to learning the outcomes from her synagogue’s security guard, and reveling or wallowing in the result with fellow shulgoers who share her dual devotion.

On Oct. 11, the Dodgers were in a winner-takes-all Game 5 against the rival San Diego Padres. Fax couldn’t watch — it was Erev Yom Kippur. But by the time Kol Nidre was over, seemingly everyone milling about in the lobby of her West L.A. synagogue knew the good guys had won a nailbiter.

“It gives you another level of camaraderie with other fans who are doing what you’re doing,” Fax, 53, said. “You don’t get the drama. You don’t get the high-blood pressure. But that’s OK. I’ll know the scores.

“And on the flip side, I love being unplugged on Shabbos and Yontif,” she added, using the Yiddish word for holiday. “I love the reprieve it gives me from the rest of the world.”

Moshe Bogoratt went to the Dodgers’ pennant-clinching victory on Sunday; he, too, will be counting on his North Hollywood synagogue’s security guard for updates. He won’t be ducking out of prayers for World Series scoops, though. Instead, he’ll let them come to him through friends circulating in the sanctuary. He’ll pass by a sports bar on the walk home from shul for one last glance.

“It’s very hard to explain to co-workers,” said Bogoratt, 30, who is a project manager for a construction company. “Like, ‘What do you mean, you’re not watching the game?’ They know how big a fan I am. They learn, like, wow, you view it as that important.”

But a man’s got to have a code, and there were lines he wouldn’t cross when it came to watching the game. I asked him if he would turn his TV on before Game 6 started next Friday and leave it on. Technically, it might not constitute a violation of Shabbat. But to Bogoratt, it would undermine the spirit of the day.

“Honestly, if I ever made that decision, I think I wouldn’t feel very good watching the games,” he said.

Fax and Bogorat’s abstention was of a piece with many other Orthodox fans I spoke to on both coasts — but not all of them.

Boaz Hepner, a nurse and Dodgers obsessive, wasn’t going to let Fourth Commandment abstractions stand between him and Shohei Ohtani. He plans to watch the Friday and Saturday games with his in-laws, who are not Orthodox and live in the downstairs half of his duplex.

He knows his rabbi might not approve, but Hepner doesn’t have trouble rationalizing what he’s doing. He views halacha, or Jewish law, as a code that either allows an action or doesn’t allow it; the perceived intent of a commandment doesn’t concern him. Therefore, as long as he’s not touching the remote or asking his father-in-law to change the channel, he can watch with a clear conscience.

Moreover, he said, not watching the game would pose a greater issue. “It will detract from my Shabbos if I’m not watching the Dodgers game,” Hepner, 45, said. “It’s not going to give me more kavana” — a Hebrew word that means focus or intention. “It’s just going to irritate me.”

He could imagine skeptics pointing to the biblical imperative not only to guard the Sabbath, but also to remember it. “I’m not texting friends, I’m not changing the channel,” he said. “I’m remembering that it’s Shabbos. There’s no part of this that I’m not remembering Shabbos.”

Mannis, the Yankees fan, was weighing another factor in his decision: his public image as an Orthodox Jew in the baseball world.

As he’s developed a social media following for his baseball content, Mannis has foregrounded his religious identity. He regularly posts on X about Jewish topics, and in his videos, he can be seen wearing tzitzit and a yarmulke. Sometimes, he says, he gets messages from strangers who thank him for educating them about Jewish topics.

“That carries some weight,” he said. “If I was on Twitter excitedly posting about how I found a hack to watch Game 1, I think these people would think it’s a little bit fake,” he said.

And if someone did turn a TV on in his apartment, he would prefer the sound off, as the Talmud seems to forbid the use of noise-making devices on Shabbat.

“It’s not something I’m pumped about,” Mannis said about the setup. “But in these rare circumstances, I’m willing to have, you know, 10% more leeway than I would during the year. And there are still hard red lines that I want to follow.

“And if God, for whatever reason, says Max’s half-witted plans of how he’s going to watch Friday night fall through, I might be a little bit annoyed in the moment,” he added. “But at the end of the day I might be like, ‘All right. Fine. That wasn’t meant to be.’”