Falling in Love With Dusty Treaties

Image by getty images

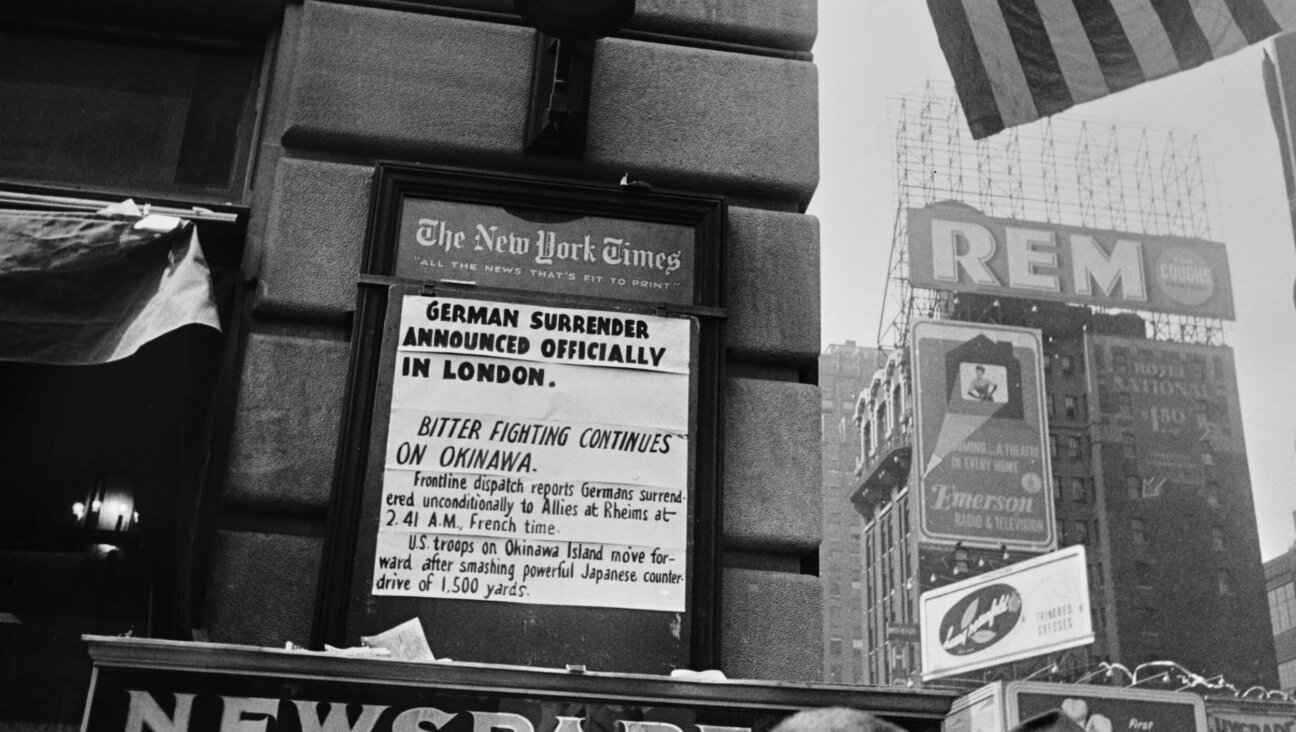

Balfour?s Back: Lord Arthur Balfour showed visitors the sights in Jerusalem in 1925. The declaration that bears the British diplomat?s name backed a Jewish homeland in what was then Palestine, but not in all of Palestine. Image by getty images

One of the more surprising twists in recent Middle East punditry is a sudden surge of interest among pro-Israel hard-liners in the fine points of international law. The topic isn’t usually popular with hawks; they tend to see it as an infringement on national sovereignty, employed mainly as a club for bludgeoning Israel. Seeing it raised in Israel’s defense is a novelty. It could be a good sign, if it gets Israel’s defenders and critics talking the same language for a change. But maybe I’m being too optimistic.

What’s got the hawks excited is a legal argument propounded by a cadre of academics, journalists and politicians, including Israel’s deputy foreign minister Danny Ayalon, purporting to show that Israel is legally entitled to the entire territory of historic Palestine, including what’s now the West Bank, Gaza and even Jordan. To prove this, they’ve dusted off the 1922 League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, which made Great Britain the legal guardian of the old Turkish backwater. Among Britain’s top duties was overseeing “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

This was actually Britain’s phrase, taken from the 1917 Balfour Declaration. But where the British cabinet could only “look with favour” on a Jewish national home, the League of Nations could and did inscribe it in international law.

The musty old text has gained a new urgency lately because of the looming collision between the Netanyahu government and much of the international community — the Obama administration, the Europeans, the Palestinians and the Arab League — over the location of Israel’s eastern border. Netanyahu is under pressure to accept Israel’s pre-1967 armistice lines as the basis for a negotiated border. Previous prime ministers, including Ehud Olmert and Ehud Barak, were willing to negotiate along those lines. Netanyahu isn’t. He claims Israel is as entitled to the territories as anyone, if not more so. Hence the mandate revival.

Unfortunately, Netanyahu’s position requires some sleight of hand. The mandate didn’t actually grant Palestine to the Jewish people. It promised a Jewish national home in Palestine, but it didn’t say how much of Palestine would be included. Nor, incidentally, did it promise a sovereign state.

The ambiguity was deliberate. Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann initially asked Britain to proclaim “the reconstitution of Palestine as the national home of the Jewish people.” After nearly a year of negotiating, the cabinet rejected that language. Instead it approved the more limited promise of “a national home [somewhere] in Palestine.” The same fight was taken to the League of Nations, with the same result.

The League did grant the Zionists one important victory: The mandate included a new clause stating that “recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine.” In other words, you don’t get the whole country, but what you do get is yours by right.

The ambiguities weren’t settled until 1947, when the League’s successor organization, the United Nations, voted to partition Palestine into two states, one Jewish, one Arab. That decision immediately superseded the mandate in international law.

We know what happened next: The Arab side rejected partition and went to war. In the fighting the unborn Palestinian Arab state was carved up. Bits went to Jordan, Egypt and Israel. In 1967, responding to Arab aggression, Israel went to war and captured the rest.

The U.N. voted that fall of 1967, in Resolution 242, to demand that the sides negotiate peace and that Israel withdraw “from territories” it had just captured. The Arab states wanted withdrawal “from the territories,” meaning all of them, but they lost.

International law had evolved again: Now the lines that held before the ’67 war were the starting point for future discussion, rather than the 1947 partition borders. The U.N. vote effectively recognized Israel’s right to the extra land it won in the 1948 war, beyond the partition borders, but not to the land it captured in 1967.

The Arab states refused to negotiate. But things didn’t end there. In 1982 the Arab League designated the Palestine Liberation Organization as the “sole representative of the Palestinian people.” In 1988, meeting in Algiers, the PLO finally voted to embrace the original partition plan: two states, one Jewish, one Arab. Finally there was a negotiating partner.

In 1993 Israel and the PLO signed an agreement, the Oslo Accords, to work together toward an unspecified resolution of their differences. Most of the blanks were filled in a decade later, in President Bush’s Road Map, which the two sides signed in 2002. It aimed to “end the occupation that began in 1967” and create a Palestinian state alongside Israel. As a signed agreement, co-signed by the United States, the U.N. and others, it has the force of law.

Law isn’t static. It evolves. In America, the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, requiring the return of runaway slaves, was voided in 1868 by the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal rights to all. That was narrowed in 1896 by Plessy v. Ferguson, the “separate but equal,” ruling, which was in turn replaced in 1954 by Brown v. Board of Education, outlawing segregation.

International law in the Middle East evolves in much the same way: 1922 gives way to 1947, then to 1967, which leads to 1993 and then 2002. The players evolve, too. Yesterday’s military foe becomes today’s negotiating partner and tomorrow’s neighbor.

It’s hard to see the evolution when you’re living through it. It’s even harder to believe in it after you’ve waited through decades of dashed hopes. That’s why some of us scoff at repeated PLO votes recognizing Israel, but seize on some obscure imam’s war cries as the Palestinians’ true face. It’s why others of us dismiss Netanyahu’s vows to make peace, pointing to a rogue minister or outlaw settler as the real Israel. We’d rather cling to our pessimism than get our hopes too high. It feels dangerous to be too optimistic.

Contact J.J. Goldberg at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 2

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 3

News School Israel trip turns ‘terrifying’ for LA students attacked by Israeli teens

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Yiddish קאָנצערט לכּבֿוד דעם ייִדישן שרײַבער און רעדאַקטאָר באָריס סאַנדלערConcert honoring Yiddish writer and editor Boris Sandler

דער בעל־שׂימחה האָט יאָרן לאַנג געדינט ווי דער רעדאַקטאָר פֿונעם ייִדישן פֿאָרווערטס.

-

Fast Forward Trump’s new pick for surgeon general blames the Nazis for pesticides on our food

-

Fast Forward Jewish feud over Trump escalates with open letter in The New York Times

-

Fast Forward First American pope, Leo XIV, studied under a leader in Jewish-Catholic relations

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.