Food and Faith

Five years ago, what was considered the largest immigration raid in American history trained a harsh spotlight on abusive conditions for workers and animals at the nation’s biggest kosher slaughterhouse and meat packing plant.

The raid on Agriprocessors in Postville, Iowa, and the subsequent conviction of its owner on federal financial fraud brought more than shame to the Jewish community. It also brought renewed energy and commitment to nascent efforts linking the laws of kashrut with the burgeoning food movement, to frame ethical food production and consumption through a Jewish lens.

Just 16 months after the raid, in September 2009, the Conservative movement issued its response: Magen Tzedek, the “shield of justice,” an ambitious program that was considered the most comprehensive food certification in the country, kosher or not.

Its 175 pages of guidelines were divided into five standards that companies must meet to earn this new seal, ensuring justice for workers, animals and consumers, and considering corporate integrity and environmental impact. After a three-month review, the standards were supposed to be tested in the marketplace and then released for consumers by early 2010.

We’re still waiting.

Much has happened in the Jewish world in response to the Agriprocessors scandal — and we’ll get to that in a moment — but unfortunately, much hasn’t happened, as well. Magen Tzedek doesn’t lack for passionate, committed leadership, not with Rabbi Morris Allen, the Minnesotan congregational leader who has been at the helm since the beginning. But this noble effort appears to be hobbled by three factors: complexity, opposition and apathy.

From the start, even sympathetic observers wondered if the extensive guidelines were, frankly, too much, and that worry has turned out to be prescient. Small operators say that the myriad regulations can be overwhelming and confusing. In trying to cover so many areas — from workers rights to environmental protection — Magen Tzedek may have overreached, making the perfect the enemy of the possible.

From the start, too, this effort faced opposition from those in the Orthodox movement who have a virtual monopoly on kosher certification. It’s difficult to say whether this opposition is based purely on philosophical grounds — that kashrut should apply narrowly in the religious realm, while the secular government is tasked with enforcing its own laws on labor, the environment, etc. — or whether it’s a more blatant struggle for control.

Whatever. Orthodox opposition, stated or implied, has been enough to push away already reluctant participants.

This complexity and opposition could be overcome, however, if there was a sustained groundswell of support from Conservative Jews. Yes, the leadership says all the right things. Rabbi Julie Schonfeld, executive vice president of the Rabbinical Assembly: The R.A. “continues to support Magen Tzedek, both the organization and its ideals.”

Rabbi Steven Wernick, executive vice president of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism: “The fact that Magen Tzedek has not gotten to market yet does not diminish the great value of this initiative.” Allen is even scheduled to speak at the USCJ’s upcoming centennial.

And yet there is little agitation from rank-and-file Conservative Jews or their leaders for what could have been a groundbreaking, signature attempt to meld ritual tradition with contemporary concerns. After all, the organic food movement faces extensive regulation and industry opposition, but consumer demand has made the organic label commonplace. When Magen Tzedek was first announced, a Forward editorial wondered whether Conservative Jews would care enough about kashrut to lift it to a new level. Apparently not.

The contrast with efforts to promote a Tav HaYosher, an “ethical seal,” is instructive. Four years ago, Uri l’Tzedek, an Orthodox social justice organization, launched a local, grassroots initiative to reward kosher restaurants that met three standards for their workers: The right to fair pay. The right to fair time (that is, overtime.) And the right to a safe work environment.

This seal is less ambitious than Magen Tzedek, no doubt. Still, so far more than 80 kosher establishments around the country have the Tav HaYosher, and Rabbi Ari Weiss, Uri L’Tzedek’s executive director, attributed the success to several factors. His organization doesn’t charge for certification. The standards simply reflect existing law — requiring the minimum wage, for instance, while Magen Tzedek has demanded more than that. Plus, the kind of Jews who are going to patronize kosher restaurants are undoubtedly more engaged.

“We’re working with a community that takes their kashrut seriously,” Weiss told the Forward. “There’s something about being kosher that’s part of being Jewish. The Torah also tells us not to exploit workers. We’re trying to put something else on the agenda.”

That’s not to say Tav HaYosher hasn’t faced its own opposition from within the ranks of Orthodox Jews. Weiss acknowledged that a few restaurants in the program opted out after pressure from the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, whose adherents include the Rubashkin family that owned Agriprocessors. (Sholom Rubashkin, formerly the company CEO, was sentenced to 27 years in prison.)

Why the person who washes dishes in a kosher restaurant should be denied a minimum wage because of complaints over the prison term of a convicted felon is one of the mysteries of modern Jewish life.

Another mystery is why Jews of all denominations aren’t pushing for Magen Tzedek, or a simplified, more practical version of it. The Jewish food movement is growing in so many other ways. When Agriprocessors was raided and shut down, there were about 10 communities around the country participating in Hazon’s CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture) program, buying local organic produce at synagogues and community centers. Now there are 57.

In fact, Fred Bahnson, director of the Food, Faith and Religious Leadership Initiative at Wake Forest University, travelled the country examining how different faith communities were responding to the food movement and concluded that “Jews were far ahead of Christian churches in making the link between food and faith,” he said in an interview. (And he’s a Christian.)

The explanation was kashrut. “Food is an explicit part of religious devotion and cultural heritage,” he observed. “There’s already a sensibility that food is something we should pay attention to, where in other faith traditions, it’s not as obvious.”

Sometimes it takes an outsider to make the simple but profound point. As Bahnson wisely noted, Jews already have a many-thousand-year tradition of laws governing how food is obtained, prepared and consumed so that the very basic act of nourishment is infused with an element of the sacred. At a time of mass production and global markets, that imperative is even more urgent. If Magen Tzedek isn’t feasible, then develop something else in its place, but the serious effort to link kashrut ritual with broader concerns for workers, animals and the environment cannot be forsaken.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

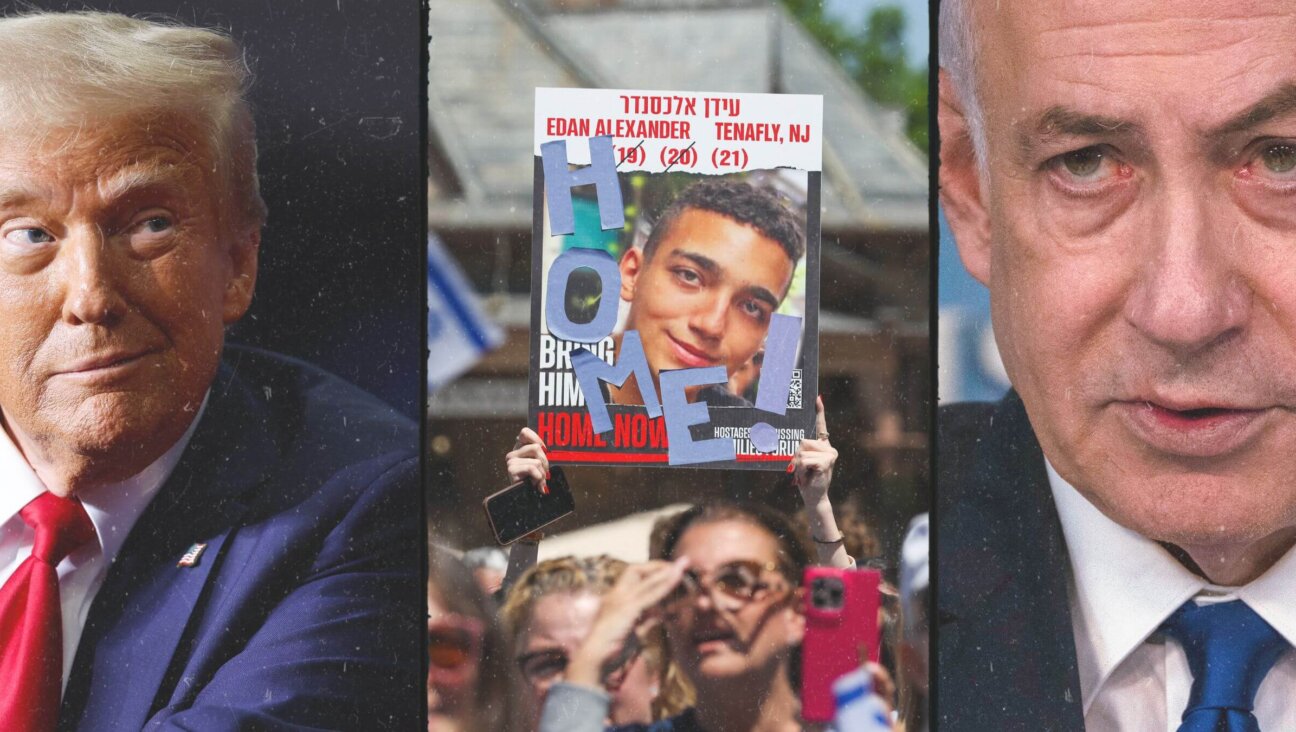

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.