Many Orthodox Americans feel more in common with Republicans than with fellow Jews

Image by Getty

Generally speaking, American Jews are liberal and identify with the Democratic Party. That is, apparently, unless you are Orthodox.

The new Pew study released this week found that 75% of Orthodox Jews identify as Republican, up from 57% in 2013, the last time a similar survey was conducted.

None of this, I would venture, is news to anyone.

Many reasons have been proposed for why Orthodox Jews are increasingly aligning with the Republican Party over the past decade. It might be Israel, or religious liberty, or a whole bunch of issues that convinced Orthodox Jews to make that decision and enthusiastically support President Trump.

What is new, however, is that Orthodox Jews have begun to feel as though they are at “home” in the Republican Party and in the conservative movement.

My grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, who loves me as only a grandmother can, does not get upset with her grandchildren. That is, unless I write or say something that she sees as critical of anyone on the political right — or if I were to be mean to another one of her grandchildren.

Politics is the sport of choice, and hardly a day goes by when I don’t see outward signals of political identification in my community. Bumper stickers and flags have become the norm, and Orthodox kids are picking up politics at younger and younger ages. To borrow the phrase Buzzfeed published in its standards and ethics guide, “we firmly believe that there are not two sides.”

Like it or not, the Republican Party is now our mishpacha.

It has not always been that way. I remember, as a child, going with my parents to vote, as they — then registered as Democrats in New York — pulled the lever at one time to reelect Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and another time to vote for Republican Rudy Giuliani. They were the quintessential moderate Democrats, both immigrants, tailor-made to be swing voters.

They have both since switched their registrations to Republican. As the years passed and political polarization reared its ugly head, they — and many like them — felt the “middle-of-the-road” wasn’t a place they could occupy any longer.

It is a sentiment they share with many Democrats today, who don’t want to welcome anyone who won’t toe the extreme progressive line.

So instead, my parents are now Republicans.

To be clear, I am pretty uncomfortable with how much of our identity we have begun to define through a political prism. Are our policy positions really what makes us who we are? Especially for Jews, who already possess a rich tradition formed through millennia of law, wisdom, and culture — does it make sense to allow political tribalism to become a key part of our identity?

For many Americans, as our nation becomes less and less devoutly religious, politics has become a sort of secular religion. It is no coincidence that those American Jews who do not see following Jewish Law as essential to being Jewish — and who see “working for justice and equality” as something three to 13 times more critical to being Jewish — also generally identify as progressive.

Much of our political tribalism manifests less in what we stand for than what we stand against. As the left coalesced against Trump, many Orthodox Jews became caught in the crossfire. Our very existence — as Jews who do not toe the party line — challenges and discomforts them.

As researcher Erica Brown of George Washington University told the Forward’s Arno Rosenfeld, “There’s a lot of micro-aggression coming from non-Orthodox movements toward Orthodox Jews. There are ways that progressives speak about Orthodox Jews that they would never speak about people of color.” Pew shows us just how true this is.

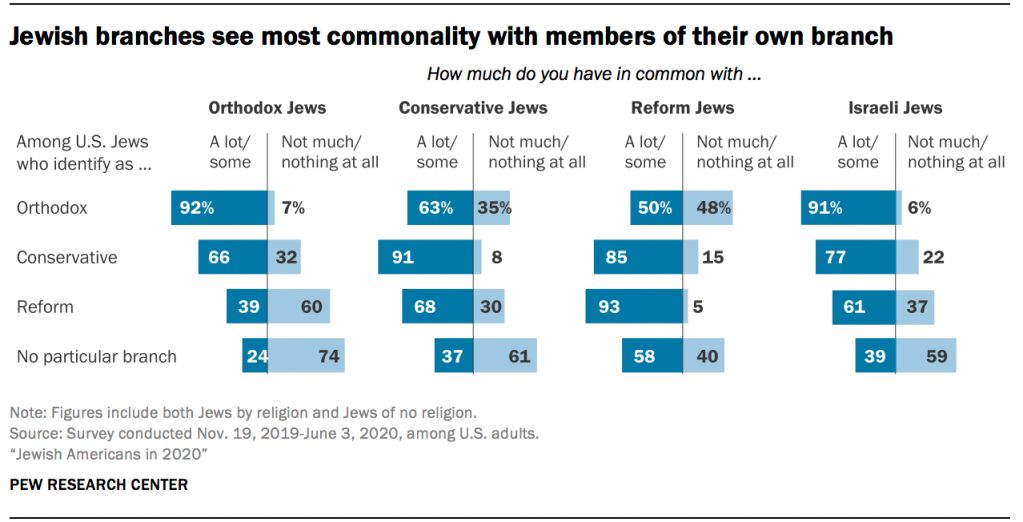

Of the 69% of Jews who are either Reform or have no religious affiliation, only a little more than 34% said they felt they had anything in common with Orthodox Jews. Moreover, 78% of the “Jews of no religion” — a group which is twice as likely to self-identify as “very liberal” — said they had “not much” to “nothing at all” in common with Orthodox Jews.

At the same time, over half of Orthodox Jews — for all the depictions of closed-mindedness — still manage to find some commonality with Jews of all stripes.

Many Orthodox Jews survey a world — even a Jewish world — which is increasingly hostile toward us and everything we stand for. More and more, our traditions and our mores are outside of the mainstream, and the same allowances which are made for other minorities — religious or otherwise — never seem to be granted to us.

We see that, and we want no part of that. That is another reason why for so many, the Republican Party and political conservatism have become “home.” And yes, some — like their counterparts on the left — have adopted their politics with an almost religious conviction. Is it that hard to understand when it is religious fervor that drove them there in the first place?

Eli Steinberg lives in New Jersey with his wife and five children. They are not responsible for his opinions, which he has been putting into words over the last decade, and which have been published across Jewish and general media. You can tweet the hottest of your takes at him @HaMeturgeman.