Odessa, Ukraine has a rich Jewish baseball history

Fewer than 200 Jews have played in the majors. But three Jewish players born in Odessa, the Ukrainian city now under heavy Russian siege, excelled in their adopted sport.

Four members of the Detroit Tigers baseball team pose in the dugout on July 5, 1932. From left, Ukrainian-born Izzy Goldstein (1908 – 1993) and Americans Harry Davis (1908 – 1997), Gee Walker (1908 – 1981), and Heinie Schuble (1906 – 1990) Photo by FPG/Getty Images

Who knew that Odessa was a hotbed of baseball?

Since 1900, fewer than 200 Jews have played in the majors. In the early years, they were mostly the children of immigrants who learned to play in city playgrounds and parks.

But three Jewish players were themselves born in Eastern Europe — and they were all born in Odessa, the Ukrainian city now under heavy Russian siege. Born decades apart, they each represent three different generations of Jewish immigrants.

William Cristall, Reuben Cohen and Isidore “Izzy” Goldstein each arrived in this country as foreigners. But by playing baseball and reaching the major leagues, if only briefly — they became Americans.

By the late 1800s, Jews comprised about one-third of Odessa’s roughly 200,000 residents. It was the home of major synagogues, a center of Jewish literature and learning and the birthplace of klezmer music. Frequent anti-Jewish riots led to waves of Jewish emigration, mostly to the United States.

Baseball was unknown in Odessa when Cristall, Cohen, and Goldstein each arrived in America as young children, but they learned the game soon after they reached America’s shores.

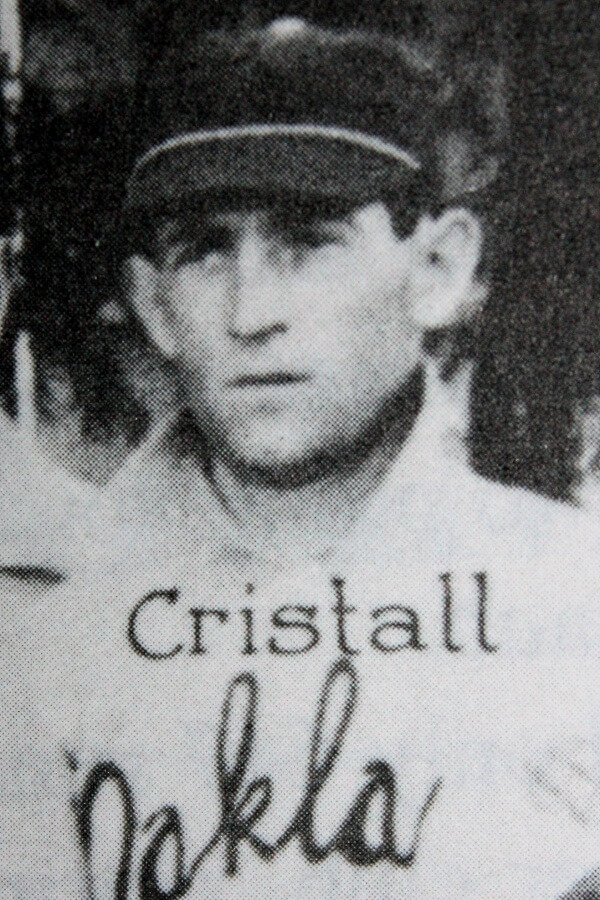

Born in Odessa in 1875, William “Bill” Cristall and his family were part of the first wave of Eastern European immigrants to the United States. They settled in Buffalo, New York. By 1898, he was playing in the minor leagues and by 1901 he was promoted to the Cleveland Blues in the American League.

On September 3 of that year, he became the first American League rookie to pitch a shutout in his major league debut, defeating the Boston Americans (now the Red Sox), giving up only five hits. Unfortunately, he lost his next five starts, recording a win-loss record of 1–5. For a pitcher, he was a respectable hitter, with 7 hits in 20 at-bats, including two triples, and finished with a career .350 batting average. He was the only Jew on a major league roster that year.

Cristall returned to the minors from 1902 to 1917, playing for 11 different teams. The Pittsburgh Press in 1909 described him as “bouncing around the minors for lo these many days, bending southside slants and spitter over the chafing dish for epicurean batters.” He compiled a 77-119 win-loss record and occasionally played outfield.

After his playing days ended, Cristall had brief stints as a minor league manager and worked as an umpire for seven years in the International League. He died in Buffalo on January 28, 1939.

Reuben Cohen was one of many Jewish ballplayers who changed their names to avoid anti-Semitism, although in his case the name change served another purpose. Born in Odessa in 1899, Cohen immigrated to the U.S. with his parents in 1904, settling in Hartford, Connecticut. He was a basketball, football and baseball star in both high school and college. His college baseball coach was also a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals — in June 1921, while still a student, the 5-foot-5, 145-pound Cohen spent a week as a shortstop on the Cardinals roster.

To escape anti-Semitism but also to maintain his amateur eligibility in college, he played under the name Reuben Ewing.

But the ruse didn’t work: Newspapers continued to call him by his Jewish name. The Richmond (Indiana) Paladium-Item in July 1921 explained that Cohen had adopted the new name “for ballplayer purposes,” reminded readers that another major leaguer, Sammy Bohne, had changed his name from Cohen, and mused, “just why these fellows think the name is a handicap is not clear.”

As Ewing, Cohen played in just three games, and struck out during his one at-bat.

The Cardinals sent Ewing to its minor league teams, but by the end of the season, he was out of professional baseball. Reverting to using his original name, he returned to college and played his three favorite sports, and returned to Hartford after graduation. There, he worked as a realtor, played for and coached the Young Men’s Hebrew Association basketball team, and joined Bnai Brith and other Jewish organizations.

Like many Jewish immigrants, the circumstances of Isidore “Izzy” Goldstein’s early life — including the year of his family’s arrival in the U.S. — are obscure. Baseball websites claim he was born in Odessa on June 6, 1908, but his army records say he was born a year earlier.

The Goldsteins lived in the predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Soundview in the Bronx. An indifferent student, he dropped out of George Washington High to play semi-pro baseball but soon the baseball coach at James Monroe High School lured him back to school, promising that his teammates would do his homework and take his tests if he’d pitch for the baseball team. There he joined future Hall of Fame slugger Hank Greenberg, his Bronx neighbor. The two of them led the school to the city finals.

Goldstein again left school to sign with the Detroit Tigers. After three years in the minors, he was called up to Detroit in 1932.

On February 27, 1932, the Detroit Free Press boasted that while two New York teams, the Yankees and Giants, had been seeking a Jewish player to put on their rosters, the Tigers had “slipped into New York and grabbed a pair of Jewish players from right under their eyes.”

But Goldstein and Greenberg never played together in Detroit. Goldstein’s only stint with the Tigers was in 1932, when Greenberg was still in the minors. Greenberg got promoted to Detroit the following season, but by then Goldstein was back in the minors.

The 6-foot 160-pound hurler earned his first win on May 24, 1932 against the St. Louis Browns. In 16 games (six as a starter) he pitched 56 innings, won three games and lost two. As a good-hitting pitcher, he had five hits in 17 at-bats for a .294 average.

In midseason, Goldstein was demoted and never returned to the majors. He pitched for the Toronto Maple Leafs for the rest of the 1932 season and for the entire 1933 season. For the next five years, he played semi-pro ball for several New York City teams, including the popular Brooklyn Bushwicks.

Following his baseball career, he worked in the men’s wear retail business , interrupted by a three-year stint in the Pacific theater during the Second World War. He retired at the age of 68, moved with his wife to Florida, and died in Delray Reach in 1993.

In 1903, an immigrant father wrote a letter to Forward editor Abraham Cahan, concerned that his son was spending too much time playing baseball instead of pursuing a more intellectual hobby like chess. In his advice column, Bintel Brief, Cahan responded that parents should allow Jewish children to play baseball with their friends.

“Baseball is a good way to develop the body. It’s better than gymnastics. First of all it’s out in the fresh air,” Cahan explained. “Let’s not raise our children to be foreigners in their own country.”