Buried in a wedding gown: The real-life ‘Corpse Bride’ haunting my childhood

Understanding a heartbreaking story through Jewish history, traditions and folklore

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

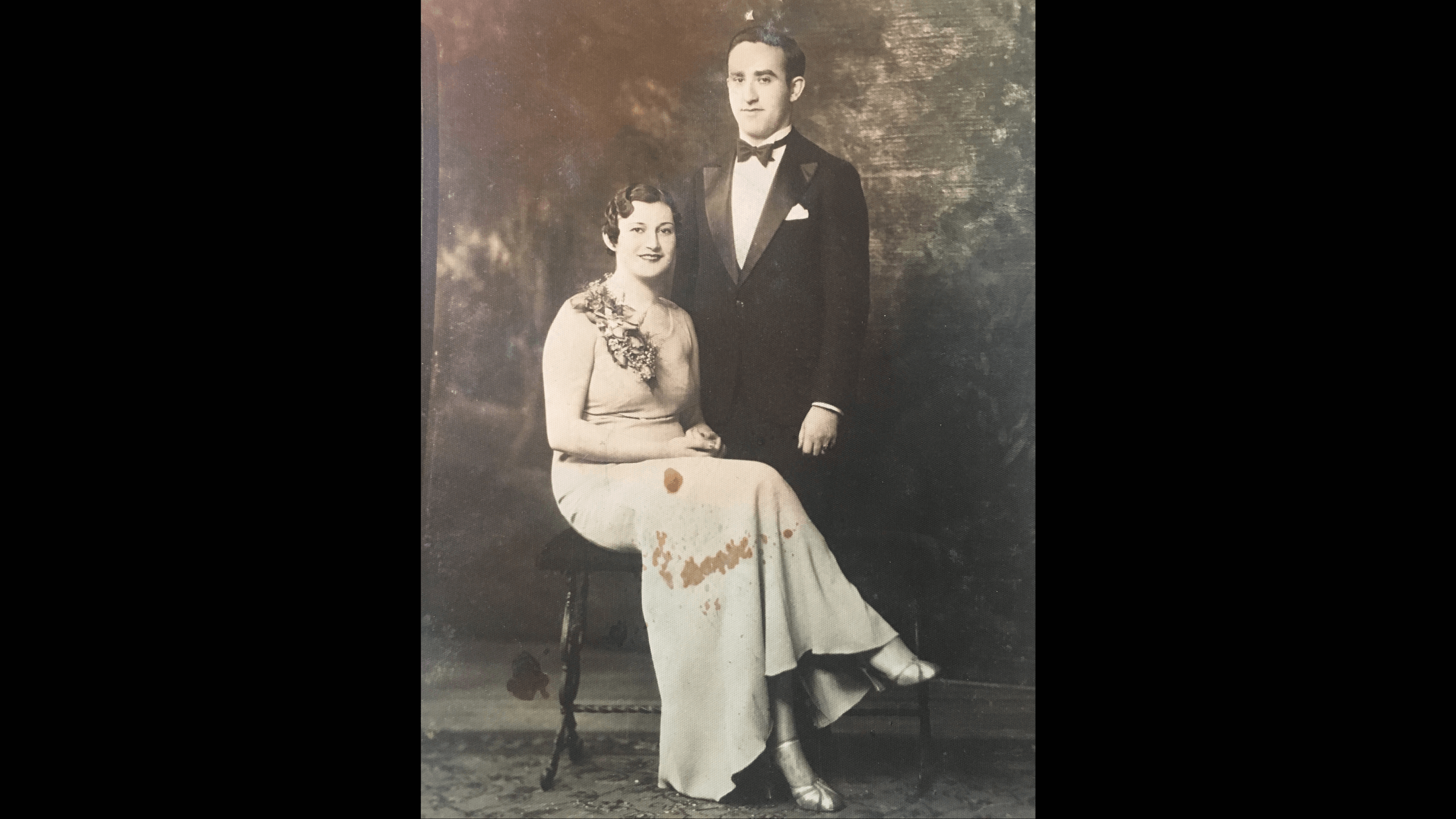

It was always 1933 in my mother’s one photograph of Fanny, her hair bobbed like Garbo’s, her eyebrows thin, penciled arcs. Her silk skirt flowed to her shoe buckles. Her arms were fleshy, the way women were in that pre-fitness craze era. She stood next to her fiancé in front of a forest backdrop, the photo clearly a studio portrait, the flowered carpet swept clean of leaves.

I stared at this photograph and remembered when I first learned about Fanny. I was 5 or 6 years old. My mother was reading me to sleep. I asked her to put down the Grimm’s and tell me one of her own stories:

“Lightning bolts zigzagged across the sky,” she said. “Silk rustled, a coffin lid closed and caught on the edges of Fanny’s magnificent gown.”

It was a tragic tale, but one that I never tired of hearing: Fanny had died just five days before her wedding, and she’d been buried in her bridal gown. When I thought about it, it felt like I was suffocating, like I was trapped in a box myself. What I didn’t know was that the story of Fanny’s burial was a place holder for a larger and more traumatic narrative.

For most of my life, I’d believed that burying Fanny in her wedding dress was a singular choice made by my family, a departure from typical burial customs. What my mother hadn’t known is that in Orthodox Judaism, burying a murder victim in their clothing is ritualized. “The individual is not washed or dressed in the typical shrouds. They need no further purification,” as Shira Telushkin wrote in the Tablet. Not that Fanny was a murder victim: She wasn’t. Her appendix had ruptured and she didn’t get to the hospital in time. But her untimely death, right before her wedding, seemed as unjust as if she’d been killed. The custom might seem ghoulish to those unfamiliar with it, but burying Fanny in her wedding gown made sense within a traditional construct designed to alleviate trauma.

Tim Burton’s movie “Corpse Bride”

Watching Tim Burton’s animated film “Corpse Bride,” I felt like Fanny’s burial had been brought to the screen. Johnny Depp voices a groom who gets thrown out of his wedding rehearsal for not having learned his vows. Gnarly tree branches and a murder of crows haunt the setting, which looks vaguely like the old country in Poland or Ukraine. The groom goes off to practice, placing his fiancée’s wedding ring on a slender tree branch. When he finally gets the words right, the branch changes into a finger belonging to a figure in a tattered wedding gown, voiced by Helena Bonham Carter. This ghostly bride reveals that she was murdered on her wedding day. The ground opens up, transporting the pair to a subterranean Land of the Dead where the groom is trapped among legions of ghouls and skeletons, along with a black widow spider. Eventually, though, the dead bride’s murder is avenged and all live happily ever after.

What most viewers don’t know is that the fabric of ancient histories, folklore and practices are woven into Burton’s film. The tale of a corpse bride can be found in a 17th-century text documenting the exploits of a legendary rabbi, Issac Luria of Safed, and it’s retold in “The Finger,” a story in Howard Schwartz’s “Lilith’s Cave: Jewish Tales of the Supernatural.” I find Burton’s cultural appropriation to be heinous. Even more so, because the history of the Jewish people is fraught with corpse brides — including attacks on brides and wedding wagons during pogroms, as documented in Yizkor Books commemorating Jewish life before World War II.

Burton’s film never overtly acknowledges the source of the story, though it has been written about. The Jewish News of Northern California wrote that Burton got the idea for the movie when his late executive producer, Joe Ranft, brought him excerpts from the original legend, and a Mental Floss story noted that “allusions to Judaism were omitted because, according to co-writer John August, Tim gravitates toward a universal, fairy-tale quality in his films.”

But life in the Pale of Settlement was far from a fairy tale. What I know about my relatives’ lives before their immigration is that they were destitute, battled diseases like typhus and ringworm (“Don’t lie down on the carpet, you’ll get ringworm,” my grandmother warned in 1970s suburban Philadelphia) and that they lived in constant fear of pogroms. For my grandparents, crossing the Atlantic was like a return from the Land of the Dead. But they were so shattered by what happened there that they spent the rest of their lives in reaction to it.

A trip to Ukraine

Six years ago, I found my grandmother’s birth certificate in an online copy of a Russian ledger, along with the rest of her mother’s family records. Nearly all my great-grandmother’s siblings remained in Ukraine, in the towns of Zviahel, Ozeryany and Tluste. On the first day of Sukkot in 1942, German soldiers marched them into a forest or to Belzec, an extermination camp, and murdered them along with their children, grandchildren, and in-laws. My hands shook when I encountered the descriptions of what had happened. Yet as I received this knowledge, similar to unveiling both the Jewish context behind Fanny’s wedding dress burial, and the source for Burton’s film, I felt one step closer to becoming whole.

In 2018, I was able to travel to Ukraine to search for more evidence of my relatives’ lives and deaths. They lie in ghastly moss-covered mass grave sites in abandoned cemeteries, with most of the towns’ current inhabitants unaware of their existence. Though the Nazis and then the Soviets destroyed nearly all traces of Jewish life, some unclaimed homes have eerily been left to stand, like half-eaten gourds rotting on roadsides. I entered one of them in Ozeryany. A gray-haired man in his late 80s led me through the door. I touched the doorpost and felt the nail holes where a mezuzah had once been affixed. He told me the surname of the family who had lived there. My jaw dropped. It was the same as my great-grandmother.

At the end of Burton’s film, revenge triumphs over death. With the groom’s assistance, the corpse bride poisons the man who murdered her. The act of avenging her death releases her from her zombie state, and she is transformed into a swarm of butterflies, thereby absolving the groom of his obligation to marry her. He marries his original intended bride, creating a happy ending for all.

Fanny’s death, of course, cannot be avenged. And we can’t create a happy ending for those who perished in pogroms or wars or for that matter, on the eve of their wedding day. But if we’re afraid to correspond with ghosts, we risk becoming trapped in the Land of the Dead. Moonlight won’t illuminate our bodies. We become trapped in the present, in a box with only one dimension. Learning their stories and putting the pieces of their shattered lives back together can help make us whole, and that brings us back to the land of the living.