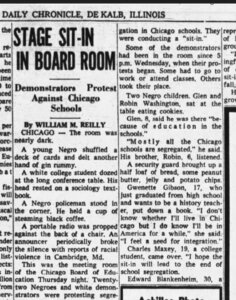

I was a child at a civil rights sit-in. 60 years later, what’s changed?

Battle over racially segregated Chicago public schools involved Jewish students as well

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Sixty years ago this month, an interracial group of civil rights activists staged an overnight, multi-day sit-in at the Chicago Board of Education.

I was one of them.

“Two Negro children, Glen and Robin Washington, sat at the table eating cookies,” read a United Press International report on July 12, 1963.

“Glen, 8, said he was there ‘because of education in the schools. Mostly all the Chicago schools are segregated,’ he said. His brother, Robin, 6, listened.”

The reporter got Glen’s age wrong; he was 9 — and the article could have also described us as Jewish children. But our understanding of why we were there was spot-on, and it has since become one of my most powerful childhood memories.

Our mother, Jean Birkenstein Washington, was a leader of the city’s Congress of Racial Equality chapter, and the sit-in was planned in our living room. Earlier, while on maternity leave, she co-wrote an article for the NAACP detailing how Chicago’s school boundaries were drawn along neighborhood racial lines, creating overcrowded schools that were 90% Black while majority-white schools had ample space for students.

The Chicago school system’s Black and white de facto segregation — as opposed to de jure, or by law, in Southern states — also segregated Jews. Frequently my mother commented that the newly constructed Mather High School “was built to keep the Jews out of Taft.”

Other ethnicities were also affected, with the inequities starkly revealed in district maps she’d clandestinely acquired (they weren’t public in those days). One school’s boundaries stretched a mile long and a block wide, coinciding perfectly with the Puerto Rican strip on the city’s Near North Side.

The Chicago school system’s Black and white de facto segregation — as opposed to de jure, or by law, in Southern states — also segregated Jews.

By the 1963 sit-in, Glen and I were movement veterans. Two years earlier, we participated in a “wade-in” at an unofficially segregated South Side beach. I thought every family did those things.

At the sit-in, the school board chairman initially said publicly we could “stay as long as you want.” Throughout the week, sit-inners came and went, and I can’t recall how many days my family stayed overnight.

But it ended abruptly when police forcibly removed the protesters — arresting 10 — on the ninth day. One newspaper account documents I was there moments later, when the group picketed on the sidewalk out front. A photo shows me in short pants, gripping a sign that’s bigger than I am. Glen is a few feet in front of me, rounding the corner. The wording on the signs — “Segregated Chicagoland” is unmistakably the lettering of my art teacher mother.

So was the sit-in successful?

At first, it seemed so. Embarrassed by the district maps now made public, the school board agreed to CORE’s demands — primarily to abolish all districts and create magnet schools. But they quickly reneged and struck a side deal with CORE’s chapter president, agreeing to only minor district changes. Most schools remained overwhelmingly segregated.

Disillusioned, my mother stepped back from the movement, never forgiving the chapter president. At her memorial service 40 years later, a fellow activist told me there was something she never knew: Two of the sit-inners were caught smoking marijuana, and the board had threatened to expose them unless our side backed down.

“She wouldn’t have cared,” I responded, and she would have said let them get arrested. Jean never smoked or drank, and at meetings at our house always served lemonade. “If you want a drink, go to a bar,” she’d say, stressing that this was a revolution, not a social hour.

Eventually, in 1980, the school board signed a consent decree with the U.S. Justice Department, whose lawyers were armed with the maps I led them to in our basement.

As demanded years earlier, the board agreed to desegregate and create magnet schools. Yet more than 20 years afterward, three-quarters of Black students still attended segregated schools, and the numbers have changed little today.

Civil rights leaders downplayed the effort as a loss, instead accentuating the more successful, (and to the outrage of the world, more violent) Birmingham, Alabama, campaign two months before. The even more world-changing March On Washington came the next month.

Glen and I didn’t go to that one; children under 14 weren’t allowed, so my 18-year-old foster sister Sibylle represented the family.

Anniversaries can spark teary-eyed nostalgia, but by no means is that an excuse to let your guard down. The attacks this very moment against affirmative action, voting rights and diversity, equity and inclusion make it painfully clear that justice and equality are far from achieved.

But stories of the past can rekindle energy and nourish the spirit — like a child eating cookies in a boardroom in the middle of the night.