Israel will not defeat Hamas in Rafah without confronting Gaza’s future

Before invading Rafah, Israel must work with regional partners to avoid a humanitarian disaster for the Palestinians

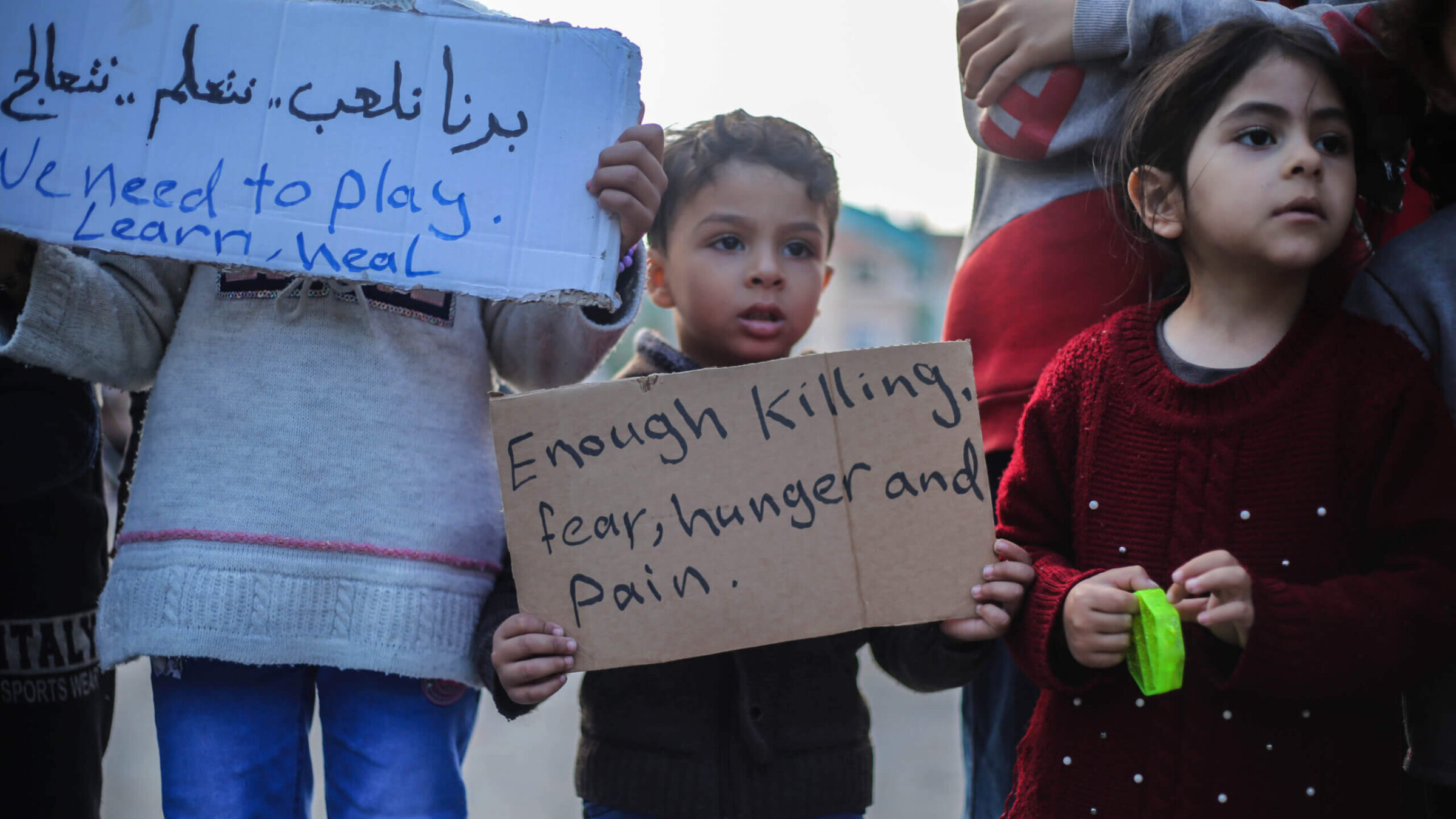

Palestinian children hold placards during a march demanding an end to the war, Feb. 14, in Rafah, Gaza. Photo by Ahmad Hasaballah/Getty Images

Monday morning, Israel awoke to the shock of good news: Overnight, Israeli forces raided a building in Rafah and freed two living Israeli hostages from Hamas captivity: Fernando Marman (60) and Louis Har (70).

While providing the country with a much-needed morale boost, Marman and Har’s rescue further complicates the calculus surrounding the next high-stakes decision facing Israel’s war effort: when to launch a full ground operation in Rafah, Hamas’ final stronghold.

Israel’s leadership may see the present as a politically opportune moment to attack the southernmost city in the Gaza Strip in the hopes of bringing more hostages home. But the drawbacks of doing so currently outweigh the benefits without substantive measures to minimize the diplomatic cost for Israel and the humanitarian cost for Palestinians.

Assuming that an Israeli invasion of Rafah is inevitable — even if delayed due to Israeli reticence or a new hostage deal with Hamas — Israel and its regional partners must work together to address Israel and Egypt’s concerns and prevent a greater humanitarian disaster. This cannot happen without answering political questions related to Gaza’s future that the Israeli government has thus far avoided.

The Rafah quagmire

Israel has legitimate cause to invade Rafah. According to Israel, Rafah is home to four Hamas untested battalions that it has yet to confront. There is also the Philadelphi corridor, the narrow strip along the Gaza side of the border with Egypt. Seizing that corridor will allow the IDF to destroy cross-border smuggling tunnels that serve as Hamas’ economic and logistical lifeline. Israel has periodically carried out airstrikes on Hamas targets in Rafah since the war began, although it is only a matter of time before it puts boots on the ground.

But invading Rafah now will have severe repercussions. Sandwiched between active war zones and destroyed neighborhoods to the north and the international border with Egypt to the south, the 1.5 million Palestinians now sheltering in Rafah have nowhere obvious to seek refuge. Fearing an influx of Palestinian refugees unable to return home, Egypt has signaled that an Israeli invasion of the border town could prompt diplomatic retaliation, including a suspension of diplomatic ties that have existed since the 1979 peace deal.

Last week Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that he had ordered the army to develop a plan for evacuating Palestinians from Rafah. Simultaneously, Israel stepped up its airstrikes on targets in Rafah, resulting in dozens of Palestinian deaths over the weekend. Although Israel has not yet issued a local evacuation order for Rafah, Netanyahu’s rhetoric and the rising casualty count have the region on alert.

Under pressure from the U.S. and Egypt, Netanyahu has promised that Israel would take steps to minimize the humanitarian repercussions and would not expel Palestinians southward into Egypt.

But such assurances are less than credible. Three weeks ago, 12 ministers and 15 coalition Knesset members attended a conference in Jerusalem focused on building Jewish settlements in Gaza and encouraging a so-called “voluntary transfer” of Palestinians.

With the government declining to present a real vision for Gaza’s political future, there is a real concern that the far right could leverage its unprecedented political power to execute its own messianic one. Netanyahu’s lukewarm denials offer little comfort.

No safe place for Gazans

Current conditions on the ground in Gaza are also not conducive to resettling 1.5 million Palestinians internally. When Israel began its ground incursion into Gaza in October and began evacuating Palestinians from northern Gaza, it identified a 20-square-kilometer coastal strip next to Khan Younis known as al-Mawasi as a humanitarian zone for internally displaced persons.

But al-Mawasi does not meet the international community’s standards for a humanitarian zone and is not recognized as such by the U.N. and humanitarian NGOs. This remote area is cramped, ill-equipped, unsupervised, and lacks basic services to meet the needs of current displaced people there, let alone many more who may need to flee Rafah.

There is a good chance that many Palestinians will opt to violate an IDF evacuation order and instead remain in Rafah. Civilian deaths will assuredly be high, even in comparison to previous stages of the war.

As Palestinians flee en masse from Rafah — whether to al-Mawasi, quieter corners of Khan Younis or the central camps, or even back to Gaza’s largely ravaged north — there is no mechanism in place to ensure Hamas does not emerge in civilian areas where the IDF isn’t actively carrying out counterterror operations. We are already witnessing a Hamas resurgence in parts of northern Gaza where the IDF has thinned out its troops.

Israel estimates that Hamas acquires a staggering 60% of the humanitarian aid currently entering Gaza. Hamas’ control over aid distribution indicates its enduring control over civil affairs in the territory, a clear sign for Israel that taking out Hamas’ military capabilities alone is not enough to uproot the organization.

Whatever gains Israel makes against Hamas’ official fighting force in Rafah would be offset by a rebounding Hamas civilian presence and counterinsurgency elsewhere in the strip. The escalating humanitarian crisis, meanwhile, will heighten diplomatic pressure on Israel from the West and the Arab world to end the war with Hamas largely unchallenged as the dominant player in Gaza.

Given all of these complicating factors, an invasion of Rafah at this stage of the war would be a strategic mistake for Israel. It would engender regional ire, exacerbate Gaza’s humanitarian crisis, and potentially fuel Hamas’ reemergence in other areas.

The day after is now

Israel eventually has no choice but to defeat Hamas’ battalions in Rafah and seize the Philadelphi corridor if it wants to complete the job of removing Hamas from power. But there are certain conditions that need to be fulfilled first.

On Tuesday, Israel, Qatar, Egypt and the U.S. reportedly made progress in advancing a hostage-release deal with Hamas in exchange for an extended temporary ceasefire. If these efforts succeed, Israel should take advantage of the pause to create conditions that are conducive to a successful Rafah operation. Even without a negotiated pause, Israel should take time to plan for the eventual influx of displaced people northward to ensure humanitarian needs are met by an entity other than Hamas.

To do so, Israel needs to start confronting a question it has thus far avoided: what replaces Hamas in Gaza in the immediate term.

Israel needs to begin serious discussions with the Egyptians, Qataris, Saudis, the Palestinian Authority and other regional players to determine who will assume civil and eventually security responsibility in areas where Hamas has been defeated. Establishing an interim administration that is neither Hamas nor Israel is the only way to minimize a Hamas guerilla campaign or efforts to dominate the distribution of aid.

In parallel, Israel needs to work in coordination with the U.N. and international humanitarian organizations to establish properly equipped zones for temporary housing that have sufficient services and advance the strip’s reconstruction. Before Israel moves into Rafah, it needs to ensure IDPs can relocate to a location that offers both safety and, eventually, opportunity.

Such steps are easier said than done, take time to implement, and require meaningful buy-in from players other than Israel. But they are all necessary conditions for defeating Hamas.

Most crucially, to enlist productive regional and international involvement in Gaza, Israel must substantively commit to eventual Palestinian self-rule — including a horizon for statehood.

The cost-benefit analysis surrounding the inevitable invasion of Rafah highlights a core truth about the war in Gaza: Defeating Hamas takes not only military might, but also a viable political vision. Israel can only kick the can down the road on considering what will replace Hamas for so much longer.

To contact the author, email [email protected].