Society agrees suicide is a tragedy. Why would anyone praise the immolation that took an airman’s life?

Aaron Bushnell’s act of protest in front of the Israeli embassy made a mark — and may have set a devastating example

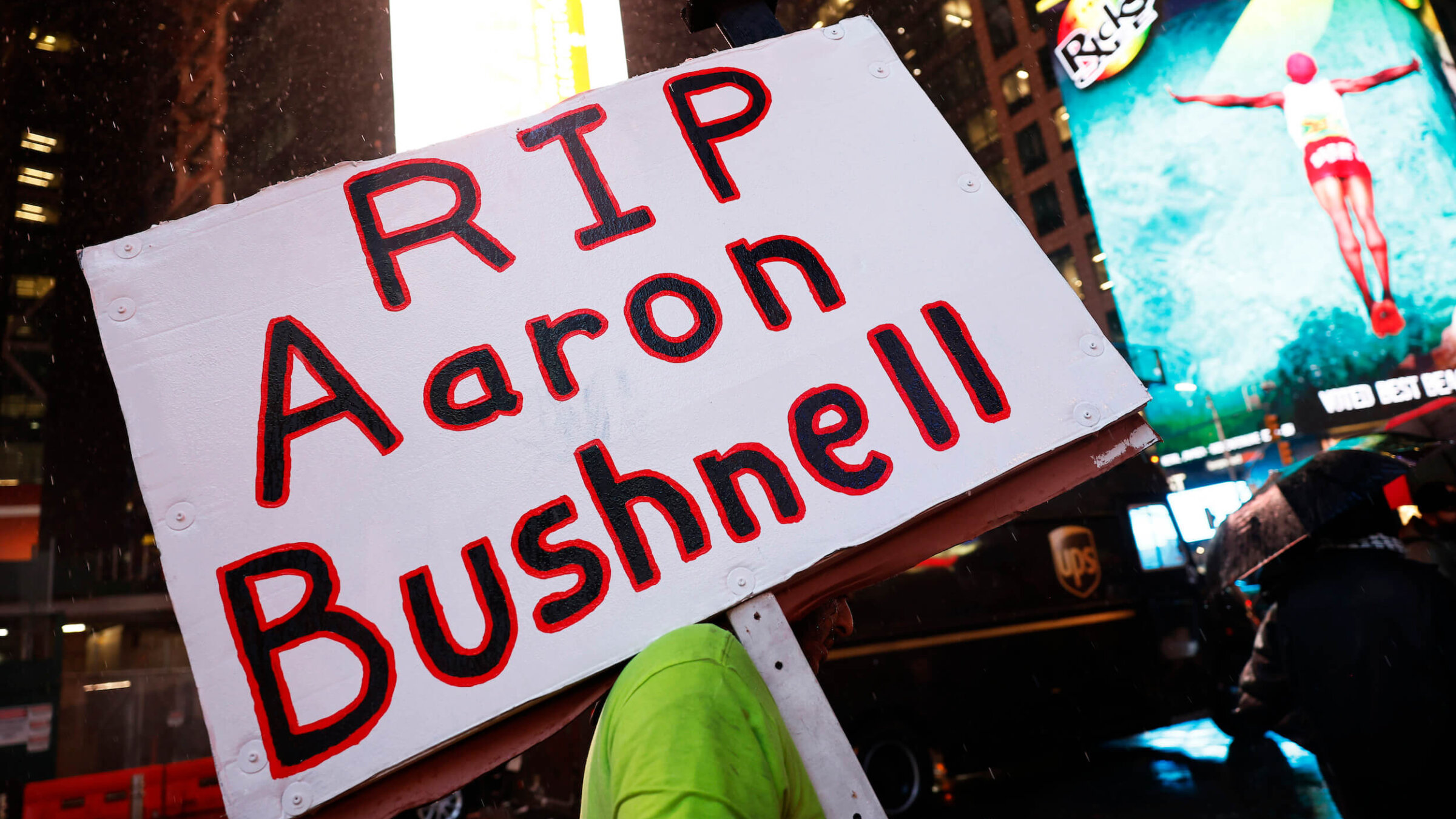

A person holds a sign during a vigil for Aaron Bushnell at the U.S. Army Recruiting Office in Times Square Feb. 27. Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This article makes references to suicide, which some readers may find upsetting. If you or someone close to you is suicidal or in emotional distress, please call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 for confidential support.

Last week, a 16-year-old girl from Palo Alto died after stepping in front of a train. Her suicide, which took place about 2 miles from my house, ignited a community-wide conversation about mental health among teens in the Silicon Valley. There were vigils, and increased counseling services made available throughout local schools. Parents — myself included — talked to each other about what more we could do to make sure teens in trouble have more resources to turn to.

The incident was deemed a tragic loss of life, and the community around the girl and her family has been in mourning. We are all asking ourselves how this could have been prevented — the typical response to a suicide.

Fast forward to this week, when a 25-year-old man named Aaron Bushnell lit himself on fire while screaming “Free Palestine” in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C. Bushnell later died in the hospital from his injuries.

This case of self-immolation has been praised by many as an act of protest against Israel’s war in Gaza. Immediately, all over social media, Bushnell was hailed as a martyr and freedom fighter.

On TikTok, people commented on videos of the incident, which Bushnell livestreamed on the livestreaming platform Twitch, calling the now-deceased man a “true hero” and wishing that he “rest in power.” On X, formerly known as Twitter, philosopher and independent presidential candidate Cornel West urged his followers to “never forget the extraordinary courage and commitment” of Bushnell — a post viewed by more than 6 million people.

All of these comments, an endless parade of praise, seem to miss one fundamental truth: Bushnell died by suicide. And suicide — per my own recent experience in my own community — is not something our society is supposed to glorify.

The concept of self-immolation as a form of political protest is not new, and has been used for centuries. And Bushnell is not the first person to light themselves on fire in protest of Israel’s actions in Gaza: In December, a woman with a Palestinian flag self-immolated outside of the Israeli consulate in Atlanta (she survived).

One of the best-known cases happened back in 1963, when a Buddhist monk lit himself on fire on a busy street in Saigon. His protest of anti-Buddhist actions by the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government was captured by a photographer, and the picture of the monk sitting still as flames engulfed his body became one of the most haunting images from the Vietnam War.

More recently, self-immolation also played a role in planting the seeds for the Arab Spring. In 2010, a Tunisian fruit and vegetable vendor lit himself on fire in protest of state and police corruption, an incident that became a catalyst for the uprisings that swept several Arab countries, including Tunisia.

But while someone who willingly burns themselves to death could be doing so out of desperation to call attention to a cause or injustice, as in the examples above, they’re still taking their own life — a deeply tragic thing. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, while suicide rates declined in the United States in 2019 and 2020, they were up 5% in 2021, and showed an increase of nearly 3% in 2022, when close to 50,000 people died by suicide in the U.S. (The CDC has not yet made data for 2023 available.)

The extraordinary personal tragedy of Bushnell’s death by suicide has, unfortunately, been completely lost in the mass of martyr talk taking place on social media.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about Bushnell, an Air Force cyber specialist who was based in San Antonio, Texas. But details are starting to emerge. As several people who knew him told The New York Times, he was raised in an isolated religious commune called the Community of Jesus, and had recently become increasingly disillusioned with both his upbringing and his military career. Those familiar with Bushnell also said he had thrown himself into “leftist and anarchist activism.”

Bushnell’s social media posts painted a portrait of someone who cared deeply about Palestinian suffering and was against the Israeli military offensive in Gaza. But, at least according to current reports, he didn’t have personal ties to the region.

At the very least, these emerging details should prompt all of us to ask some tough questions about the factors that motivated Bushnell to take his own life. And whether or not his motivation was purely to draw attention to what he saw as an unjust war — and to U.S. support for it — he died by suicide, an act which, regardless of your politics and position on the matter, is not supposed to be celebrated on social media.

One of the conundrums of dealing with suicide and suicidal tendencies is something called the “Werther Effect,” a phenomenon in which cases of suicide increase after the publication of news about them. This makes it tough to simultaneously raise awareness of such a devastating growing public health problem and prevent it from spreading.

And yet, Bushnell’s suicide is not only being spread online, but glorified. The original video of his self-immolation has been taken down by Twitch, but has nevertheless continued to proliferate on social media platforms — most of which not only have rules against depictions of suicide but also against promoting, normalizing or glorifying acts of self-harm.

To be sure, Bushnell’s self-immolation was meaningfully different from the death of the 16-year-old girl in my town. But let’s be real: Both were cases of suicide. And it’s not just social media platforms who should do a better job of treating such acts with utmost care and sensitivity. It’s all of us.