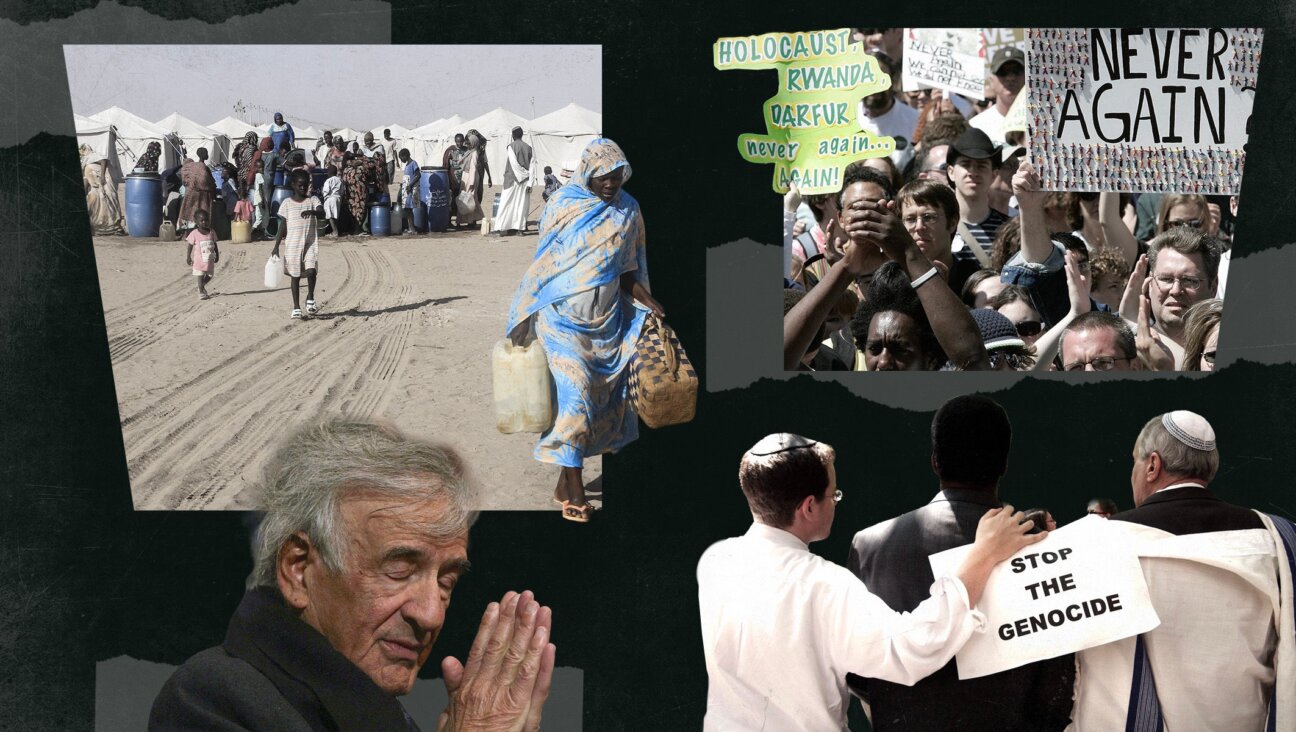

Israel’s use of torture is a travesty — just like it was for the French in Algeria 70 years ago

History repeated itself in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib. With Israel’s treatment of prisoners, it’s repeating itself again.

Algerian suspects waiting to be searched and questioned in Algeria, 1956. Photo by Getty Images

This year marks the 70th anniversary to the start of what is known as la guerre sans nom, or the war without a name: the Algerian war of independence against France. It was on Nov. 1, 1954, that the major nationalist movement, the National Liberation Front (FLN), attacked several French military and civilian targets — the spark to a conflict that consumed both the colonized and colonizers in a frenzy of military actions and guerrilla raids, merciless repression and inevitable reprisals, horrifying acts of terrorism against civilians on both sides that ended only with the Peace Accords of Evian in 1962.

But though the war ended, the ethical questions it raised persist. The most pressing of these questions is, quite literally, la question — the phrase used then by the French when they spoke about the unspeakable: torture. By 1957 and the Battle of Algiers — recreated by Gillo Pontecorvo in his iconic documentary by that same name — the practice of torture by the French military, which included physical beatings, waterboarding and electric shocks, had become commonplace. Yet, at the same time, it was the practice whose name political and military officials, fully aware of its widespread use, dared not speak.

By 1958, the wall of silence, already beginning to crumble, collapsed with the publication of La Question. It was written in a prison cell in Algiers by Henri Alleg, the offspring of Russian Jews who had immigrated first to England, then to France. Alleg, the editor of an independent newspaper in Algiers that, because of its reporting on French atrocities, was shut down in 1955, went into hiding, but was eventually caught and imprisoned by les paras, the feared paratroop division most closely associated with la question. After being subjected to torture for several weeks, Alleg remained in prison for three years, until he escaped in 1961.

Shortly after its publication, Alleg’s book was banned by the French government. This gesture was historic: La Question was the first book to be banned by a republican government in France since the 18th century. It was also futile: More than 60,000 copies of the book had already been sold. By the time the book was outlawed, it was clear that the government was abetting outlaws in Algeria. Until then, the French public could pretend that its government was not committing the irreparable in Algeria. But that was no longer possible after Alleg’s plain-spoken account of what happens when one is waterboarded — “In spite of myself, all the muscles of my body struggled uselessly to save myself from suffocation”—or is jolted by an electric wire lodged in the throat — “I could feel as if my eyes were being torn from their sockets, as if pushed from within.”

The cognitive dissonance on this subject was especially pronounced in France. Less than two decades had passed, after all, since the Germans practiced many of the same methods of torture on suspected members of the French resistance. Recalling the work of Gestapo torturers during the Occupation, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in his journal Les Temps Modernes, “Frenchmen were screaming in agony and pain: All France could hear them. In those days, the outcome of the war was uncertain and the future unthinkable, but one thing seemed impossible in any circumstances: that one day men should be made to scream by those acting in our name.” But the impossible proved all too possible, Sartre observed. Even worse, France had until now been “almost as mute as during the Occupation, but then at least she had the excuse of being gagged.”

Thanks to Algeria, Sartre concluded, the French had discovered “a terrible truth: that if nothing can protect a nation against itself, neither its traditions nor its loyalties nor its laws, and if 15 years are enough to transform victims into executioners, then its behavior is not more than a matter of opportunity and occasion. Anybody, at any time, may equally find himself victim or executioner.”

Two decades ago, Americans made this same, sordid discovery at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, where soldiers and civilians subjected prisoners to similar forms of punishment parading as interrogation. (Interestingly, the Pentagon held a screening of Pontecorvo’s film in the summer of 2003, apparently to illustrate approaches to counter-insurgency, and it continues to be shown at military academies.) And now, it seems, it is Israel’s turn as its citizens confront a series of sickening accounts about what is being done in their name.

Since the first weeks of Israeli’s military response to the horrific Hamas attack, stories on the mass arrests and mistreatment of Palestinian suspects began to appear. As early as November 2023, Amnesty International sounded the alarm about cases of “torture and degrading treatment” of the more than 2000 Palestinians taken into custody. But as Tal Steiner, director of the Public Committee against Torture, emphasized, “It was particularly hard to get the public interested, especially for a worldview stating that even when your blood is boiling and the reality is unbearable, you must maintain your humanity — and Israel must not descend to the moral level of Hamas in its relationship with the people under its absolute control.”

It was only this past April, when Haaretz published a letter by an Israeli doctor at the field hospital/detention camp in Sde Teiman, that the terrible truth became clear. Since October it has served as a triage center for hundreds of Palestinians suspected of belonging to Hamas or of committing acts of terrorism. In the letter, the doctor described amputations done on prisoners whose legs had gangrened from shackles. This is a “routine event,” he added, where all prisoners are always shackled on their wrists and ankles. Since the very beginning, he warned, “I have faced serious ethical dilemmas. More than that, I am writing [this letter] to warn you that the facilities’ operations do not comply with a single section among those dealing with health in the Incarceration of Unlawful Combatants Law.”

Some of these prisoners have since been released, and others have been reassigned to different prison facilities. But there is no evidence that the abuses have stopped. Last week, Volker Türk, the High Commissioner for Human Rights at the United Nations, issued a report. In the document, Türk referred to testimonies in which prisoners described how they were waterboarded or electro-shocked, suspended from the ceiling by their feet or burned by cigarettes — all forms of torture familiar to Alleg — as well as being deprived of food, water, and sleep. “The testimonies gathered by my Office and other entities,” he concluded, “indicate a range of appalling acts…in flagrant violation of international human rights law and international humanitarian law.” It must be added that Türk also highlighted the “appalling conditions” of the Israeli hostages in Gaza, as well as the many reports of sexual violence against the women held in captivity.

It was also last week that Israeli military police raided Sde Teiman with warrants for the arrests of nine reservists suspected of the “aggravated sodomy” — rape, in plain English — of a Palestinian prisoner. The arrest led to the storming of the police facility by a large group of extreme-right wing Israelis, including Knesset members and government ministers, who demanded the liberation of the “heroic” soldiers who had been detained. Afterwards, one right-wing Knesset member vowed to convene a hearing not on the those who participated in the riot, but on those who ordered the arrests.

This is a situation that even Sartre, the author of the nightmarish Nausea and No Exit, could hardly imagine: Citizens of a democratic state who acknowledge the state of reality and accept the state of law being gagged by a different kind of occupier: the radical settler movement which demands the annexation of the occupied territories and denies, at best, the reality, in the words of Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, that there exists a “Palestinian people.” And, at worst, these same fanatical Israelis deny, as did their ideological mentor Meir Kahane, the very humanity of those same people.

The reports of torture will finally put to rest the illusion that some of us still harbored — namely, that the Jewish people, victims of one of history’s greatest instances of inhumanity, were somehow immunized against treating other human beings as less than human. While a torturer’s boot rested on his head, a battered Alleg warned him that the world would know how he died. When the torturer sputtered “No nobody will know anything,” Alleg replied, “Yes, everybody always knows.” In the dark light thrown by Sde Teiman, everybody, including Jews, knows why we need to resist what we are all too capable of.