I teach the children of immigrants. Here’s why birthright citizenship matters.

America embraced my Jewish ancestors, and must welcome a new generation of immigrants.

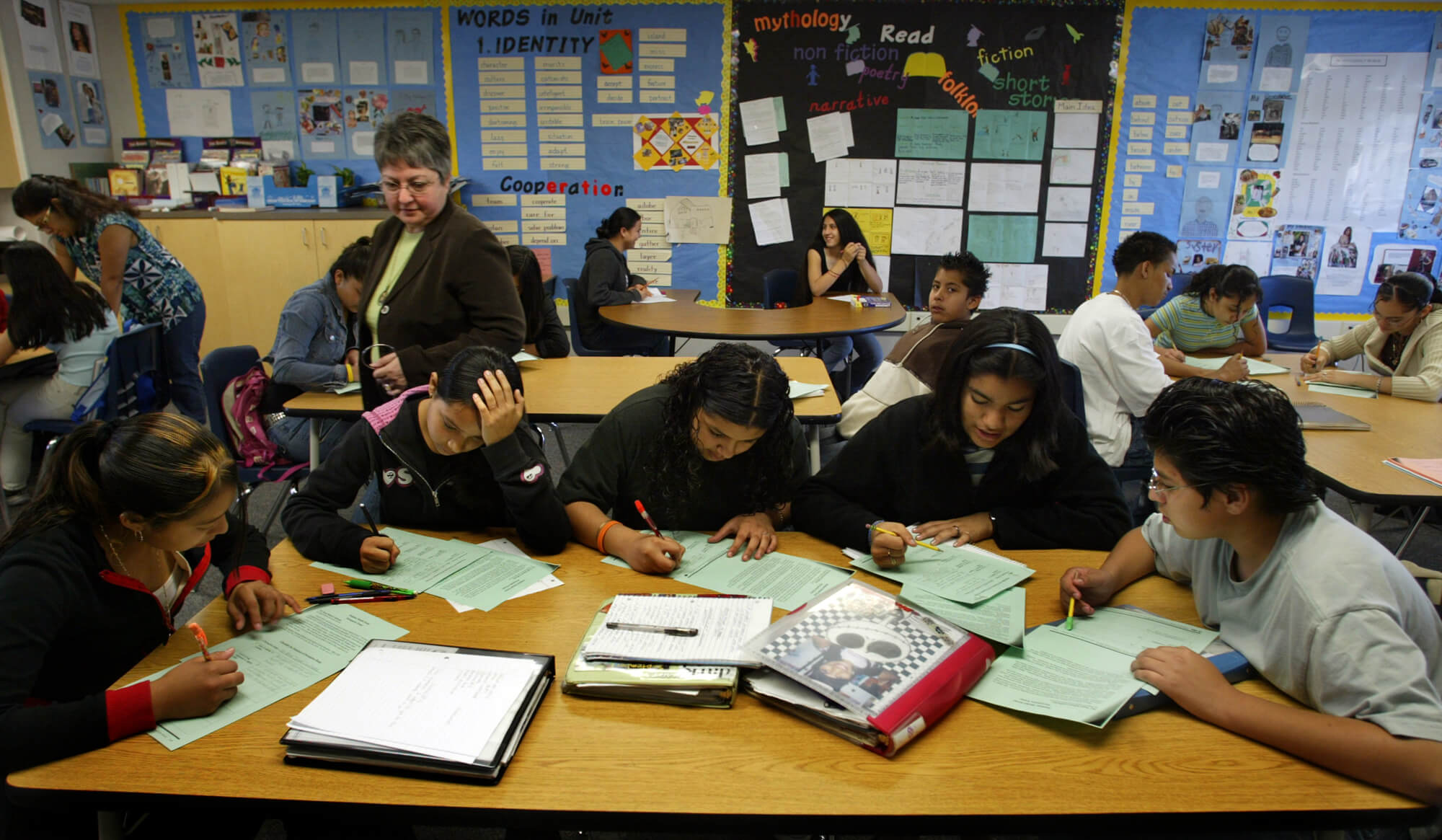

Armine Der-Karabetian, director English language program at Language Aquisition Program in Fontana, California, walks among students at the school which focuses on educating non-English-speaking immigrant children who just entered the United States. Photo by Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

In his first interview since the election, President-elect Donald Trump repeated his well-worn claim that birthright citizenship is a uniquely American invention and vowed that he would rescind it.

My Ashkenazi immigrant ancestors — and the children of immigrants I’ve spent my public school career teaching — would beg to differ.

While not uniquely American — 32 other countries also have birthright citizenship policies — birthright citizenship is essential to the American dream. Trump may not be able to stop a right that has been enshrined in the Constitution since after the Civil War and has long been affirmed by the Supreme Court — but his comments have a deeply negative impact on how Americans think and act toward newcomers.

I know the legacy of birthright citizenship well. My great-grandmother Kaley left Poland in 1905 fleeing violence. She landed in Chicago, working low-wage jobs and hewing closely to traditions and customs. Her son Martin — my grandfather — was a beneficiary of birthright citizenship. He was the first in the family to own a home. The next generation, my mom, further lived out the American Dream: college and law school degrees, a career in public service and a comfortable home in a pastoral suburb.

I never met Kaley, of course, but I’ve seen and heard echoes of her arduous journey in my classroom every day for the last 20 years. As a 12th grade teacher of American government in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood of Los Angeles, I’ve gotten to know families that, like Kaley, came to America with dreams for a better life for the next generation.

They come here, in some cases under great duress, accepting that the low-wage, unprotected labor available to them is a necessary trade-off in exchange for the promise of a better life for future generations.

Consider Edward Hinojosa, my student in 2013, who wasn’t sure he wanted to go away to college. Hinojosa’s parents immigrated separately from Mexico in the 1980s and met in Los Angeles. He and his siblings were beneficiaries of birthright citizenship, just like my grandfather. With guidance and support from his family and teachers, he set off for UC Merced. He’s now my colleague in the social studies department; his classroom is a few doors down from mine.

Almost a dozen other former students — whose parents set out from El Salvador, Mexico, and other countries fleeing violence or poverty — are now colleagues. As was true of my grandfather, their achievements are shared with their parents and will have ripple effects for generations to come. Their step into those first teaching jobs — doing the same work I do, generations after Kaley came — lays the groundwork for the foundation of a middle-class American life, imbued with American values.

Trump’s threatened birthright citizenship ban would close the doors of opportunity to those who look, speak or pray differently, all traits that my great-grandmother brought with her across the ocean. Florence-Firestone has a lot in common with Kaley’s Maxwell Street in Chicago at the turn to the 20th century: Less than 10% of adults have a college education, and more than 85% of households speak a language other than English as their primary language. My students and I share a similar story of migration and reinvention; I just benefit from being a few generations removed from the origin story.

I regularly travel between these worlds, spending weekdays among my students, the strivers, and weekends among the legacies, the Jewish descendants of people who once found refuge in America. While the dissonance is real, so is the point of connection.

We, as Jews, have an imperative to look out for the most vulnerable not only because our tradition and our texts teach us to, but also because we remember that we were once on that lowest rung, hanging on for dear life, dreaming of our grandchildren’s better future, just a few generations ago. Our opportunity to stand up for strangers is a fulfillment of the core values of our people.

The imperative to stand up and say “no” to Trump’s proposed ban on birthright citizenship transcends policy. It is an assertion of the privilege we gained through our own citizenship, and an opportunity to preserve that same privilege for those in the next generation.