Entering motherhood — and an obsession with the works of an Italian Jewish literary hero

I just had my first baby. I’m introducing him to the world through the lens of Primo Levi

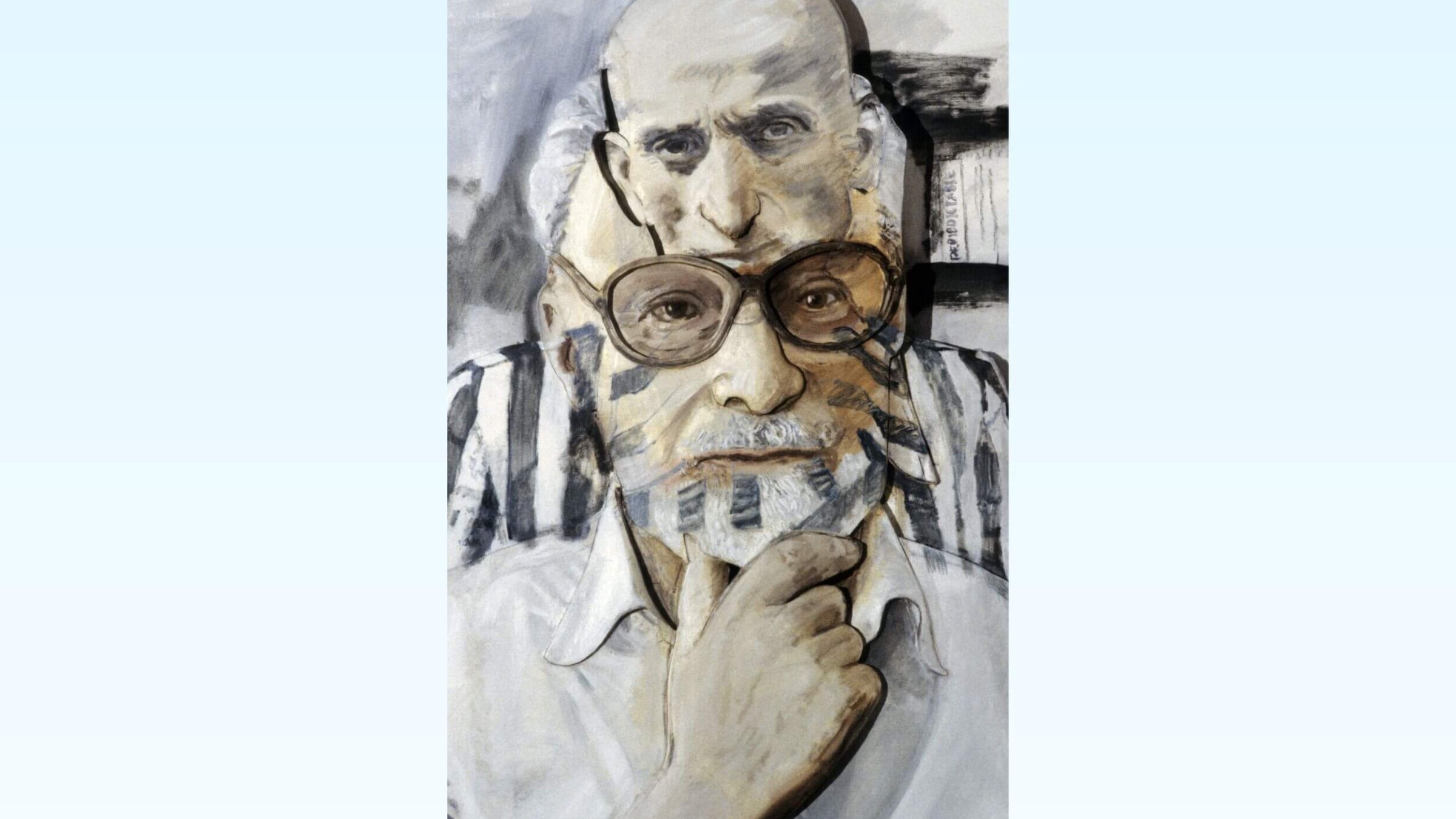

A portrait of Primo Levi by Larry Rivers. Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images

A few years ago, my husband gave me The Complete Works of Primo Levi as a gift. Last winter, I decided that 2025 would be the year I finally read through them. I was due to give birth to our first child in July, and I thought that, if I did not read them now, I never would.

I expected it might be a bit of a slog. Instead, it enraptured me. I tore through Levi’s most famous works, like If This Is a Man, his book about his year as a prisoner in Auschwitz; The Truce, which tells the story of his long journey home after liberation; and The Periodic Table, a work of genius in which various episodes of his life as a writer and chemist are retold, each having some connection to a different chemical element.

I fell in love with his short story collections, essays, poems, and If Not Now, When?, his novel about Jewish partisans in World War II. His writing, as a whole, invited me to consider life, work, memory, and the responsibility we bear toward one another. How wonderful, I thought as I finished my reading project days before I was due, that I got to do this.

And then I had my son, and wondered: Why say goodbye to Levi? Everyone says you should read aloud to babies. Why not keep on reading Levi with my son?

I’ve often felt like I gave birth in a world that is broken and warped. But in reading Levi, and books about him, to my baby, I found a kind of comfort. Levi’s writing is all about, trying, failing, and trying again to understand dignity, suffering, art and identity. Sharing it with my infant child is a way of trying to understand humanity well enough that, one day, I might be able to try to help him understand it, too.

Seeking answers in the past

I started by reading to my son about Levi. We spent early mornings, cuddling on our couch, working through A Dante Of Our Time: Primo Levi and Auschwitz by Risa Sodi, who had actually met and interviewed Levi. One morning, my husband came in from walking the dog to find me choking up while reading a passage on human suffering. He suggested that maybe we should try baby books.

And I did: Barnyard Dance and Guess How Much I Love You and Click Clack Moo.

But while I sat trying to teach myself how to nurse and my son how to latch, I listened to podcasts: Jhumpa Lahiri reading and discussing the short story “Quaestio de Centauris” for The New Yorker’s fiction podcast in 2019, Edmund de Waal and Ian Thomson, a biographer of Levi, on a 2013 episode of the BBC’s Great Lives, and a 2017 episode of the Times Literary Supplement’s podcast called “Primo Levi Speaks.”

Then I started reading Levi’s The Voice of Memory: Interviews, 1961-1987 to my son. It was all a bit ridiculous, I knew. Being a baby, this was all meaningless to him.

It’s not like I was trying to teach him — or indeed wanted him to know anything — about the Holocaust, at one or two or three weeks old. So what was I trying to do? Did I want to somehow reassure him that the past had answers for the present, the world into which he’d been born — or reassure myself?

More questions in the present

If so, it wasn’t working. Reading Primo Levi right now raised at least as many questions as it answered.

I read, for example, Levi’s criticisms in the 1980s of the government of Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, whose militarism, Levi thought, was not the answer to the questions facing Israel.

“I would prefer the center of gravity of Judaism to stay outside of Israel,” Levi once argued, adding, “I would say that the best of Jewish culture is bound to the fact of being dispersed, polycentric.” If Jews of the Diaspora disagreed with Israeli policies, he wrote, “we have the right to say to Israel: as long as things remain as they are today, you have no right to claim help, whether economic or moral, from the Jews of the Diaspora.”

I read this, some 40 years later, as Israel’s government insisted on continuing the war in Gaza, killing whole families, and allowing only minimal food in as aid, over the opposition of some of Israel’s own citizens. I wondered what my baby would one day make of his own Jewishness.

Would he want to engage with that part of his identity at all? Or would the actions of the Jewish state, the long tail of the Gaza war, and the impulse of those reactionary pro-Israel types who question the very Jewishness of Israel’s critics — a tactic used against Levi — push him away from it entirely?

I read Levi’s meditations on fascism and historical memory. “Everybody must know, or remember, that when Hitler or Mussolini spoke in public, they were believed, applauded, admired, adored like gods,” he wrote.

Days after I read those words, President Donald Trump ordered that Confederate statues be put back up in Washington, D.C., where I live. Shortly after, he took over the city’s police force, alleging that violent crime is up, even though statistics clearly show it to be down.

What would my son someday come to think about the summer of his birth, I wondered? What would I teach him about our country? Was I trying to find the teachings in these books?

When ‘understanding is impossible’

It was only when I made it to Levi’s The Search for Roots: A Personal Anthology — which is not in the Complete Works — that my Levi obsession began to make sense to me.

In The Search for Roots, Levi writes about 30 literary excerpts that had an impact on him, including the Book of Job, Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, and instructions from an old chemistry textbook. Levi suggests that four general principles run through the selections: that humans suffer unjustly; that they nevertheless have stature and can rise to meet challenges; that they are saved by laughter; and that they are also saved by understanding.

Primo Levi never stopped trying to understand the world around him. What message of love could be found in phosphorus, he asked? How could the unthinkable have happened in Germany? What did it mean for humanity that it did?

He searched constantly for meaning, even if what he often found was the truth that one can never fully grasp most things. “If understanding is impossible,” Levi told one interviewer, “knowing is imperative, because what happened could happen again.”

The quest to comprehend is a kind of salvation. In this new phase of life, for myself and for my son, I want to keep attempting it. I want to be the kind of mother who raises my child to ask questions; to tell and retell important stories; to not be constrained by authority or social opinion in his quest for understanding.

I want to give him that, not just by reading Primo Levi to him — again, he’s a little too young for most of these lessons — but by reading it for myself.

I ordered another Levi biography for me, and, “for him,” a onesie with an illustration of Levi’s face on it. He won’t get anything from that, either. But he does look very cute in it.