A Hanukkah menorah in the window for eight days? Try an Israeli flag for two years

Threats, graffiti and some very bad Yelp reviews don’t faze Elon Rubin, who owns Sundays Cycles in Santa Monica, California

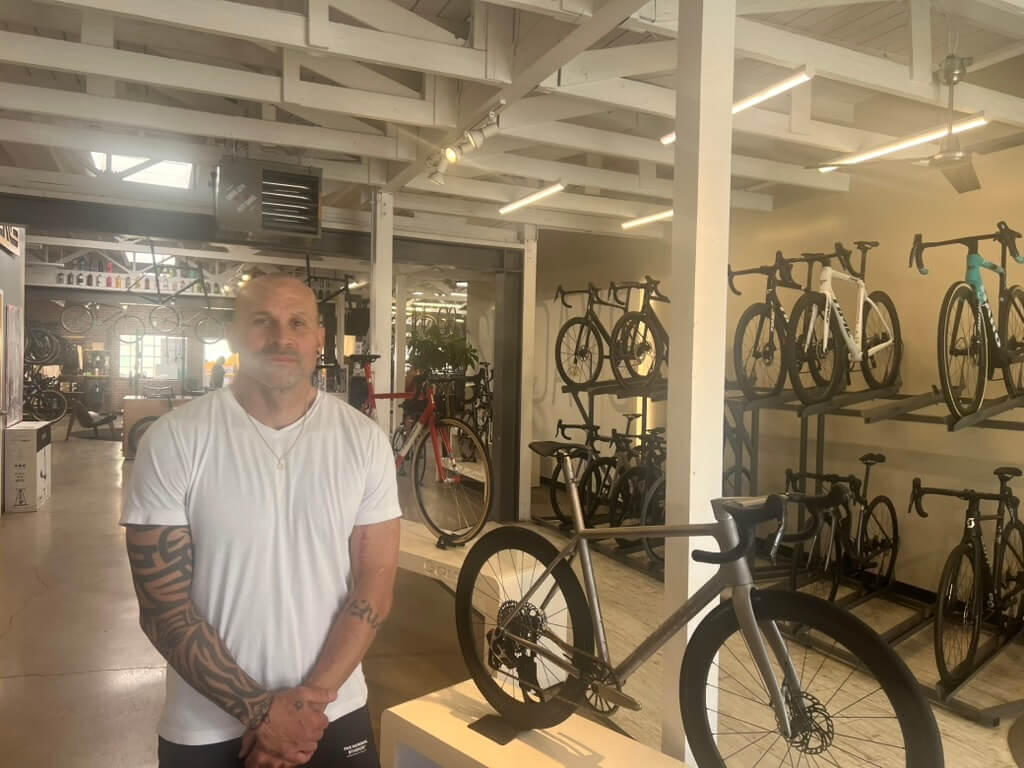

Elon Rubin, an Israeli citizen, hung an Israeli flag in the window of his bike shop after Hamas attacked on Oct. 7, 2023. Photo by Rob Eshman

There’s a robust online debate over whether Jews this year should publicly display their menorahs given the rise in antisemitism. Here’s my suggestion: Ask Elon Rubin.

Rubin owns Sundays Cycles, a custom bicycle shop in Santa Monica, California, that since Oct. 7, 2023, features a large Israeli flag in its window. Every time I drive down Main Street, passing boutiques, restaurants, nail salons and Pilates studios, I see that flag, draped inside several square feet of the glass storefront. It is meant to be seen.

“I’m an Israeli citizen,” Rubin told me when I met him at his store last month. “After everything that happened on Oct. 7, it was the least I could do.”

What drew me into the store was the simple, quiet defiance of Rubin’s decision, which stands in stark blue-and-white contrast to the constant, hand-wringing debate American Jews are engaged in over such symbols.

Those concerns bubble up to the surface like sufganiyot in hot oil around Hanukkah, when Jews are commanded to place their menorahs in windows so that they are visible to all.

The Talmud says the menorahs must be displayed to “publicize the miracle” of Hanukkah.

But more and more American Jews are worried — as European Jews have been for many years now — about announcing their Jewishness to the outside world.

Some 42% of Jewish Americans report feeling unsafe wearing or displaying Jewish symbols in public since the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel, and 40% have avoided doing so, up from 26% in 2023.

Those fears aren’t new, but they have risen as have antisemitic attacks, anti-Israel protests and online threats.

When I walked into Rubin’s spacious, hospital-clean bike shop, I asked if he shared those fears.

“There’s nothing to be scared of,” he said.

One look at Rubin and here’s the obvious rebuttal: That’s easy for you to say. The 46-year-old, born in Herzliya to an American mother and a father from Libya, came to the United States in 1998 and made a profession of his cycling obsession. He is shaved, muscled, tattooed and speaks in rapid, commanding sentences.

Over the years, numerous people have shouted at him from outside the store to take down the flag.

“I say, ‘Come in here, let’s have a conversation,’” he said. “Not a single person has come in.”

Other reactions have not been as passive. Graffiti reading “Free Palestine” has appeared on the store window, and vandals have thrown numerous eggs at the place. He’s had death threats on his phone messages, including, “I hope you die Jew” and “Your days are numbered.”

His Yelp and Google review rankings have been tanked by malicious one-star reviews.

Last March, a Jewish anti-Israel activist, Medea Benjamin, entered his store and called the Israeli flag shameful.

“What about the genocide?” she asked Rubin.

“There is no genocide,” he said.

Her Instagram post of the incident, which racked up 127,719 likes, prompted a deluge of negative reports to Instagram about the bike shop’s account. Instagram suspended his account, Rubin said, and has yet to reactivate it.

“Ten years of organic growth, gone,” he said.

But Rubin said the flag has also generated support. “For every negative,” he said, “we’d probably get two or three positives.”

Israeli tourists detoured inside to meet Rubin and thank him. American Jews, and some non-Jews, told him they appreciated the show of support.

The oddest reaction, he said, are from Jews who have urged him to take the flag down because, they said, it incites hate.

“Like it’s the new swastika,” he said.

But Rubin evinces neither fear nor loathing.

He doesn’t have “blind support” for the current Israeli government, he said, but he loves his country. Just because someone flies the American flag doesn’t mean they support President Trump, he pointed out.

It’s true that the Israeli flag, the symbol of a country embodied in conflict, is not exactly comparable to a menorah, seen largely as a religious symbol. Congregations have been divided over whether to display it on the bimah, as some congregants found it loathsome.

But someone prone to attack Jews might not make the fine distinctions between a menorah, a flag with a Star of David, and a Star of David hanging around a child’s neck, or on a Torah ark. The lines between these symbols are often blurry, but so is the logic of people who attack others just for displaying them.

I asked Rubin if he ever, in the past two years, considered taking down the flag, lighting the menorah in the backyard, so to speak.

“So then what are you?” he said. “You’re a Jew in silence, you’re a Jew in secret.”

Symbols aren’t arguments. They demonstrate but rarely convince, and nuance is not their strong suit. But to Rubin, their power lies not in the message they send to others, but in what they say to ourselves.

“Together,” he said, “we have more strength than we realize.”