With ‘Jews on Vinyl’ You Can Have Your Kitsch and Eat It, Too

“Jews on Vinyl,” an unusual museum exhibit focused on the recent Jewish past, has arrived at the Yeshiva University Museum after touring the West Coast for two years. The exhibit is a project of the Reboot Stereophonic non-profit record label, and is based on the 2008 book “And You Shall Know Us by the Trail of Our Vinyl: The Jewish Past as Told by the Records We Have Loved and Lost,” a glossy collection of over 500 vintage record covers collected over 15 years by guest curators (and Stereophonic Reboot founders) Josh Kun and Roger Bennett.

Unlike most museum exhibits, “Jews on Vinyl” is meant to be heard more than seen. Visitors choose from a handful of listening stations, impeccably set with period appropriate couches and chairs. Here they can sit and browse iPod playlists chosen by Kun and Bennett. Eartha Kitt singing “Sholem”? They have that. The Temptations doing a “Fiddler” medley? Yep. More versions of Hava Nagila than you dared imagine? Oh yes. Scattered on the listening station coffee tables are record covers representing some of the music featured on the playlists, as well as information cards with short blurbs about the artists and songs.

The gallery was mostly empty during my visit, so I could sit and listen for as long as I liked. In some ways I’m the ideal audience for “Jews on Vinyl.” To say I love Jewish music is something of an understatement. My obsession with Yiddish and Jewish music has shaped the last 20 years of my life. It’s given me an amazing community, and a sense of history and Jewish connection, I never dreamed possible as an alienated, suburban Hebrew school student.

The music featured in “Jews on Vinyl,” the neglected music of the recent past, is the raw material for my Jewish community; it’s the inspiration for musicians, ethnomusicologists, academics, dancers, folklorists, program directors and extremely informed listeners. It’s music that’s already well represented on my own iPod.

And yet, I walked out of “Jews on Vinyl” scratching my head as to what the point of the exhibit was, besides being a great way to relax after a stressful day. A good museum exhibit makes an argument. It guides museum-goers through a narrative. It raises questions that disturb the status quo and forces the viewer to examine her own preconceptions. I didn’t see that in “Jews on Vinyl.”

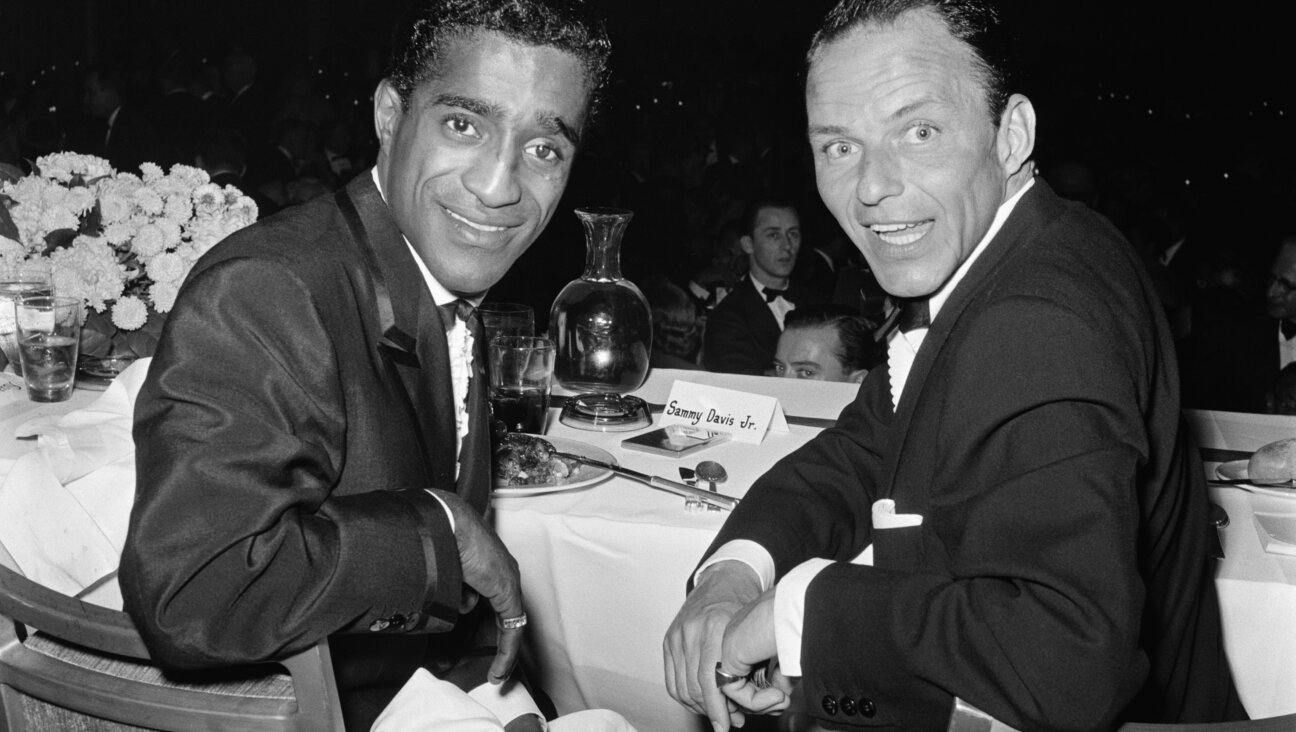

The curators do give us a thesis of sorts: “What started out as a mutual affinity for kitschy Jewish album covers (think Neil Diamond baring his chest hair on the cover of “Hot August Night” or Barbara Streisand in hot pants on the cover of “Streisand Superman”) became a quest for identity, history and customs in the sleeves of LPs. To this end, Bennett and Kun embarked on an intriguing journey, scouring the world to collect thousands of albums, and pieced together these scratched, once-loved and now-forgotten audio gems to tell a vibrant tale: How Jewish culture became mainstream American culture” (emphasis mine).

Though the exhibit text and press release nod to stories waiting to be told through this collection of record covers and music, those stories are never actually developed within the exhibit. There is no attempt at a chronology or an explanation of what “Jewish music” might actually be. Faced with hundreds of songs and record covers, we get no sense of what might be “good” or “bad,” more Jewish or less Jewish, or even what was influential and what was merely a curiosity. Sure, lots of non-Jews did Jewish material. And a Jew wrote “White Christmas.” And if my bobbe revolved 33 and a third times a minute she’d be a turntable. Nu? What’s the point? That Jewish music used to come in a lot more flavors than Debbie Freedman or Shlomo Carlebach?

I think the real point being made by “Jews on Vinyl” is that American Jewish popular culture, specifically its music, has value; it should be collected, preserved and made available to the public. And I could not agree more. But the subtext of the entire exhibit is more like, “We once thought Jewish music was irrelevant and embarrassingly kitschy. But then we listened to Jewish music and discovered it is relevant. And delightfully kitschy.” With Reboot Stereophonic we get to have our kitsch and eat it, too.

It’s clear that for Bennett and Kun, their Reboot/Stereophonic projects are exciting opportunities for exploration and self-redefinition. They get to travel the country, hunting down cool and weird Jewish music, producing CDs, hanging out with old Jewish musicians and taping their stories. I won’t lie — I’d kill for that job. Kun and Bennett are actively shaping their own Jewish identity as well as acting as important producers of Jewish culture through their many Reboot products: magazines, books, CDs, think tank retreats and now, museum exhibits. But there’s a world of difference between what Kun and Bennett do and how their product functions out in the world.

The “Jews on Vinyl” exhibit is overwhelming. A huge mosaic of album covers greets visitors at the front. The format of a handful of listening stations, and a very long playlist, means that with more than a handful of visitors to the exhibit, (or for patrons without the patience to sit and listen for more than a few minutes) it’s difficult to get more than a superficial taste of what’s offered. Radically different genres — Israeli pop, Yiddish-Latin fusion, Yinglish comedy — blur together. What does one have to do with the other? Who knows? Why should we care?

This is the problem with “Jews on Vinyl”: it’s partially hydrogenated Jewish history. Jewish culture, and Jewish music in particular, has the radical potential to animate Jewish life today and to turn passive audiences into actively engaged Jewish creators in a way that extends far beyond just music. I’ve seen it over and over at places like Klezkamp and Klezkanada where participants are empowered through their connection to Jewish music. But at the “Jews on Vinyl” exhibit, Jewish music is reduced to just another commodity. And the museum visitor is just another passive consumer, swallowing his or her obligatory dose of vitamin J.

The visitor may discover something new, or she may reconnect with a long lost musical memory. And that’s valuable. But there’s little to engage the visitor after she’s taken off the headphones. Like the iPod experience itself, “Jews on Vinyl” provides a distinctly post-modern mode of isolated connection while the music itself remains firmly situated in the past.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO