Yiddish in Texas: An unexpected language is still riding the bronco

In Houston, the “Yiddish Vinkel” has been meeting for 45 years, and now there’s even a Yiddish class for teenagers

Dana Yudovich Katz teaching a Yiddish lesson using the song “Sheyn vi di levone” (“Lovely as the moon”) to students at Kehillah High in Houston, Texas, February 2025 Courtesy of Dana Yudovich Katz

Read the original Yiddish article.

We’ve all heard the stereotypes about cowboys. But few people know that Texas has always been home to linguistic diversity, starting with Indigenous languages like Comanche and later Afro-Seminole creoles. Nearly 200 years after Texas declared independence from Mexico, a quarter of Texans speak Spanish at home.

After joining the US, the state quickly attracted new waves of multilingual settlers, even developing its own dialects of German and Czech. Today the third-most-spoken language is Vietnamese.

Texas is also home to another deep-rooted yet marginalized language: Yiddish.

Beyond New York

The golden age of Yiddish in Texas began in 1907 with an initiative to redirect the flow of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants. Instead of Ellis Island, ships from Europe now docked in Galveston, a port on the Gulf of Mexico. Legend has it that the mayor warmly welcomed the first arrivals — alongside his Yiddish interpreter.

Although most immigrants quickly switched to English, Yiddish continued to play a substantial role. By the early 1920s, Houston had a Yiddish library and Fort Worth had a bilingual newspaper. Acclaimed writers gave talks in packed halls, Yiddish theater companies made local stops, and an Orthodox Jewish immigrant to San Antonio, Alexander Ziskind Gurwitz, wrote his autobiography in Yiddish. Chaya Rochel Andres, a poet in Dallas, published her work in the language until 1990.

The leading Yiddish institution in Texas history was the Workers’ Circle, which ran after-school language programs in four of its cities. According to the historian Josh Parshall, the organization’s immigrant members wanted to pass down both their language and their secular Jewish leftism to their American-born children. The Houston school continued offering Yiddish lessons into the 1950s.

“The South is and has been a stronghold of political and cultural conservatism,” Parshall wrote in his dissertation on Yiddish politics in the southern states between 1908-1949. “That is not the only southern story, however.” For him, this diverse past is a key to reimagining the region’s future.

Yiddish on campus and in the archives

On a recent trip to Texas, I bore witness to the possibilities Parshall describes. Adrien (Eydl) Smith, who became an assistant professor at the University of Texas-Austin in 2023, teaches courses in Yiddish language and culture each day. Her retired predecessor, the folklorist and song collector Itzik Gottesman, organizes a Yiddish lunch every Friday, among other get-togethers.

One Sunday, he invited members of the Yiddishist community to his home, where I discovered that, although I live in Europe, we all had friends in common. This international language and culture is truly a velt mit veltelekh – a “world made of small worlds.”

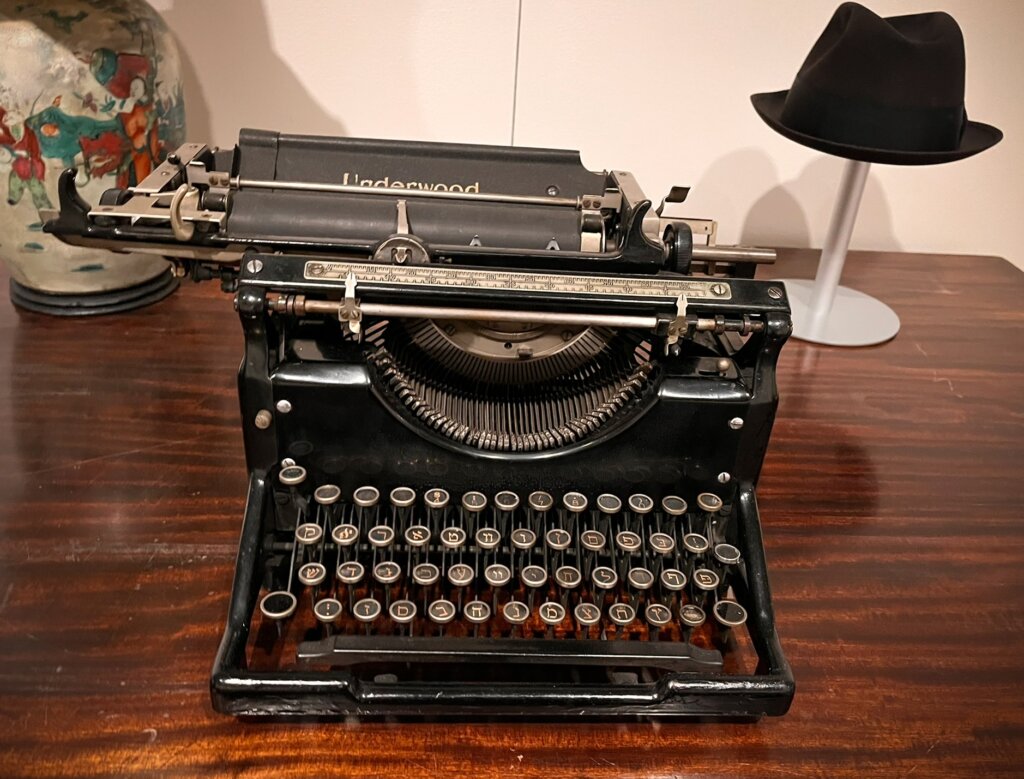

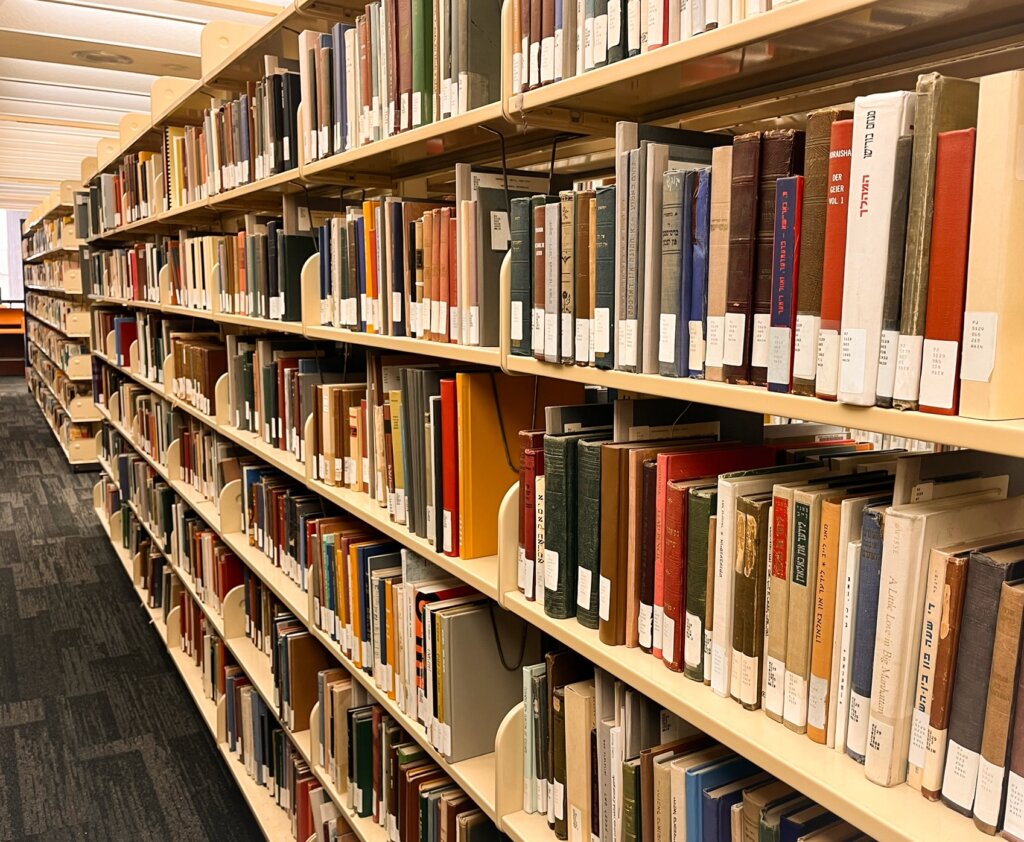

Thanks to the efforts of the late UT professor, linguist Robert King, its library includes thousands of Yiddish books. In 1979, King invited the newly minted Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer to give a lecture — and actually introduced him on stage in Yiddish. After Singer’s passing, the Harry Ransom Center, a UT-affiliated archive, acquired 177 boxes of the author’s papers to preserve them for future researchers. Today, researchers around the globe are eligible for the center’s fellowship program.

Trinity University in San Antonio has Yiddish language classes taught by Alan (Avraham-Mikhl) Astro, and in Austin, Jewish literature scholar Avi Blitz teaches online Yiddish classes for students across the state and beyond.

After the floods of Hurricane Harvey, the archivist Joshua Furman, then of Rice University, salvaged many materials about local Jewish history for a new archive on Jews in South Texas, including local Yiddish history, and preserved them in a specially controlled environment in case of future storms.

In Dallas, David Katz runs a donation-funded nonprofit called Texas Yiddish, through which he translates old documents for archives and museums in the state. He also organizes a “shmooze hour” at a Jewish retirement home, encouraging participants to use some Yiddish with their grandchildren. But despite living in a very Jewish neighborhood, he has barely anyone to speak the language with.

“I Take Pride in My Children and Grandchildren”

Houston, by contrast, has the liveliest Yiddishist community in Texas. The Yiddish Vinkel has been gathering for more than 45 years in members’ homes and at the Evelyn Rubenstein Jewish Community Center (aka the “J”). Since the pandemic, meetings have been held every Tuesday morning on Zoom, drawing new members from Kentucky to Paris.

Early last month, 30 people logged in, mostly retirees. To start things off, the group listened to a Yiddish song about minor miracles, and everyone took turns translating a few lines into English — and laughing at the bawdy innuendos.

During the second half of the meeting, the group read a Yiddish text aloud together. Barely a week after the presidential inauguration, a Bashevis Singer story about the King of Chelm seemed uncannily relevant. One woman translated the word for “law” as “executive order.”

Each year the Yiddish Vinkel organizes a “third seder” for Passover, and a cultural event to mark the anniversary of Sholem Aleichem’s death.

Although historically, Yiddish organizations throughout the world were usually run by men, I was pleasantly surprised to see that the Yiddish Vinkel is very much a matriarchy. When I requested a Zoom interview with one of its organizers, no fewer than six women showed up. True, some men are active participants, but women are clearly making the decisions.

Indeed, Yiddish activities in Houston have long been female-dominated. Frieda Weiner (1888–1990), born in Ukraine, settled in Texas in 1915 and was active in the Workers’ Circle alongside Henrietta Bell (born 1922, and still going strong at 102!). When she was 90, Weiner still led a weekly “Yiddish Hour.”

In the late 1970s, Susan Ganc, then a folk singer in her forties, met Weiner, fell in love with Yiddish, and co-founded the “Yiddish Vinkel.” Twenty years later, Barbara Goldstein — a Houston resident and recent Yiddish student — launched the Vinkel’s newsletter, which is still sent out weekly. Then, when Ganc moved to Florida, Mina Graur, a scholar of anarchism, inherited the job. Graur runs the Tuesday meetings to this day.

Referring to the people who’ve taken over the reins at the Yiddish Vinkel, Ganc said happily: “I take pride in my ‘children’ and ‘grandchildren’.”

“Hopes for the Future”

Sometimes intergenerational continuity comes down to basic scheduling. Most members of today’s Yiddish Vinkl are retired, so they are free to meet on weekday mornings – when younger adults are working.

With this in mind, Houston’s Michael Moore (no relation to the filmmaker) initiated a complementary program with classes, lectures, and film screenings called Yiddish Bay Nakht (Yiddish at Night) in 2018. Unfortunately, it didn’t outlast the pandemic.

The youngest woman at the interview, Dana Yudovich Katz, told me that she grew up in Houston. Her parents, from Mexico City, spoke both Spanish and Yiddish at home. Today, Katz brings her own children along to the Yiddish events, and has recently started teaching teens Yiddish through a Jewish extracurricular program called Kehillah High. So 70 years after the Workers Circle closed its Houston school, Jewish teenagers can take a Yiddish class once again.

After our interview, Barbara Goldstein emailed me one last thought. Houston’s Yiddish community had staying power, she said. It’s an unbroken chain of Yiddish language and culture stretching back to Frieda Weiner’s arrival in 1915. One secret to that success, Goldstein added, was that they had always cultivated younger Yiddishists to take up the baton, people like Dana Yudovich Katz. “Our hopes for the future lie with Dana!” she said.