Ukraine in the words of a murdered Yiddish poet

In June, a book festival in Kyiv featured a discussion titled “Yiddish as a Ukrainian Language”

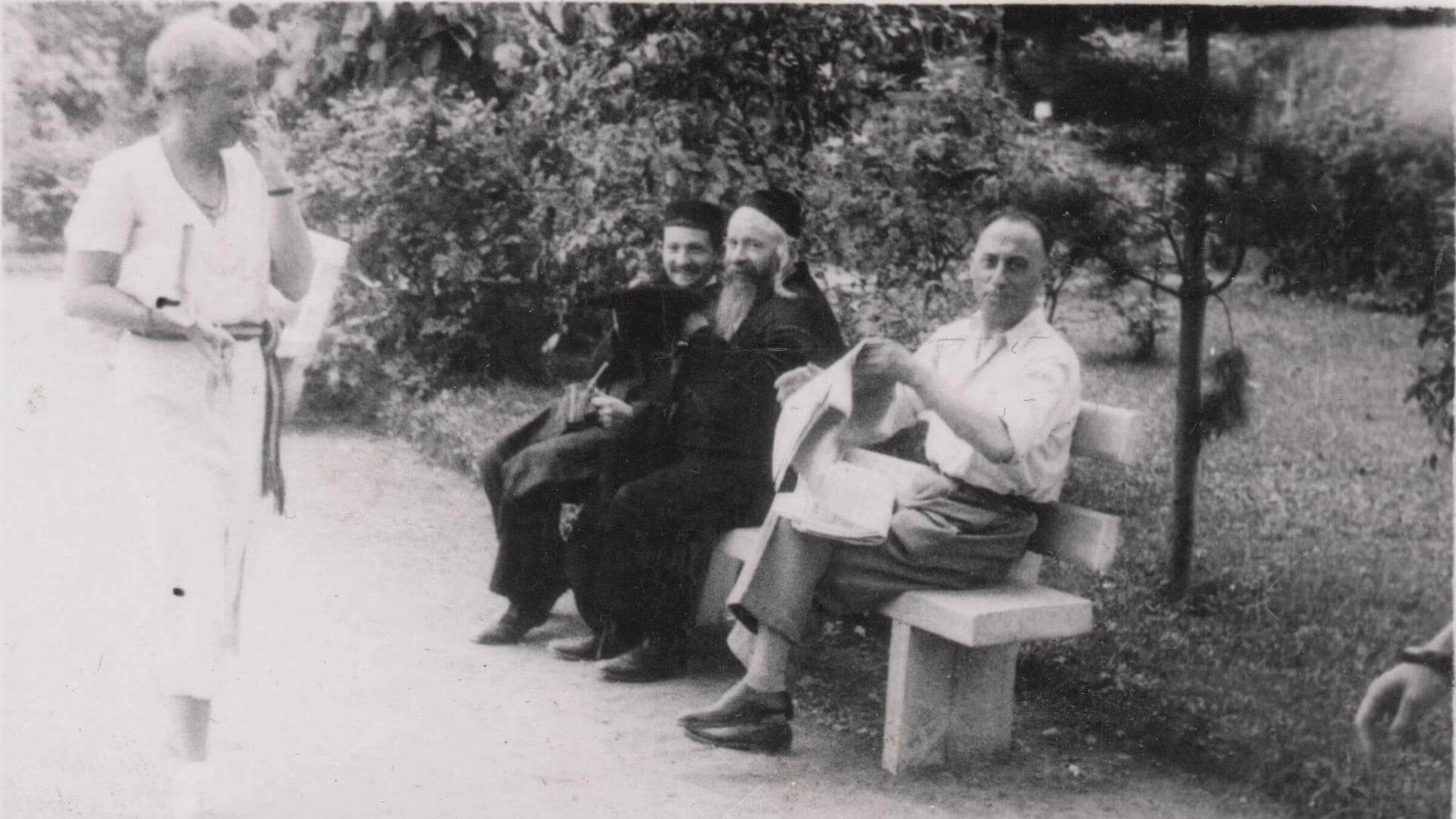

Jews in the Ukrainian town of Truskawiec, in the 1930s Photo by Wikimedia Commons

On August 12, 1952, 13 Jewish citizens of the Soviet Union were executed by firing squad in Moscow’s Lubyanka Prison. They were intellectuals and scientists, cultural figures, revolutionaries who had once supported the Soviet project. Five of them were among the most prominent Yiddish writers left in the Soviet Union, and in the world, after the language and its literature were decimated by the Holocaust.

All were also members of the Jewish anti-fascist committee (JAC), an organization formed to drum up support for the Soviet war effort against Nazi Germany. Following the war, the JAC’s focus had shifted to helping what remained of Jewish life rebuild following the war.

Though only five of those murdered were Yiddish writers, and of those five, only four were poets, Yiddish poetry itself could be said to have been a target of the firing squad. And, so, August 12, 1952 has come to be known as “The Night of the Murdered Poets.”

Yiddish organizations around the world — including Buenos Aires, New York City and Melbourne — commemorate the Night of the Murdered Poets every year, on its Gregorian calendar date of August 12. Though the five Yiddish writers murdered on that day have historically been described as Soviet, current events have drawn attention to the fact that all five of them were born in what is now the independent country of Ukraine.

Shane Baker, the executive director of the Congress for Jewish Culture, which holds a memorial event marking the Night of the Murdered Poets every year, told me that, prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion, the Congress didn’t highlight the murdered writers’ connection to Ukraine. Now, they make special note of it.

The way these writers themselves described and named the land of their birth could be confusing, mirroring the shifting of nations and borders, shaped by revolutions and invasions. I often struggle with how to phrase the relationship of Yiddish writers to Ukraine when I pitch my translations of their work to publications, particularly publications in the melting pot of the United States, which has only one official language.

It would be inaccurate to identify these Jewish writers as Ukrainian Jews, since, until Ukraine became an independent country in 1991, Ukrainians and Jews were considered distinct ethnic groups. At the beginning of the Soviet project, their national languages were Ukrainian and Yiddish, respectively, even within the territory of Ukraine itself, but both languages would eventually experience repression. Jews in Ukraine today generally did not grow up speaking Ukrainian or Yiddish as their main language, but rather Russian. President Zelenskyy famously had to study Ukrainian as an adult.

Now that Ukrainian is the official language of an independent Ukraine, it can also be challenging to convey to American audiences that Yiddish writers, some murdered over seventy years ago, hold relevance for the current Ukrainian fight against Russia. Jewish people can be as difficult to convince as anyone, however much sympathy they may have for modern-day Ukraine. Jews — not without good reason—have historically tended to associate Ukrainians with pogroms.

Within Ukraine, however, the situation may be shifting. In June, the International Book Arsenal festival in Kyiv featured a discussion titled “Yiddish as a Ukrainian Language.” And in the early months of the Russian invasion, The Algemeiner (https://www.algemeiner.com/2022/04/05/i-see-your-face-you-are-alive-the-yiddish-poet-undergoing-a-revival-in-war-torn-ukraine/) reported that a poem by Dovid Hofshteyn, one of the poets murdered on August 12, 1952, had been translated into Ukrainian and was being shared by Ukrainians on social media.

Last year, I completed a new translation of this poem into English. Titled “Ukraine,” and written during Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union, it’s a poem that feels as if it could just as easily have been penned today. Here, Hofshteyn is clear: Ukraine was his home.

Ukraine

by Dovid Hofshteyn

Translated by Maia Evrona

By blast and by smoke and by ash and by shame,

I catch sight as you raise your ruined hand,

now your head rises, bloodstained,

I see your face! Oh, you’re alive… oh, you’re alive.

Your gaze, still a child’s, now with a mother’s pain,

and the joy that arrives after peril now shines,

the clarity, that follows chaos and mistake,

like the water of spring flowing beneath ice.

I glimpse your figure rise, your frame,

to which the remnants of clothes barely cling,

and the dirty rags fall from your limbs —

It’s clear now, you are a child, all grown, you are a wife,

you are a body bright with beauty, that shines

through disgrace, through mockery, through the violence of hate.

You’re a young, unsoiled, confident might

that laughs, that transforms, that grows clear, without end,

that will fast heal its pain, its shame —

You’re Ukraine, my home,

Ukraine, my land.