Yizkor books and yentas: When New York City was a Yiddish town

Henry Sapoznik’s book is like “a raucous Brooklyn candy store full of sweets from NYC’s vintage era.”

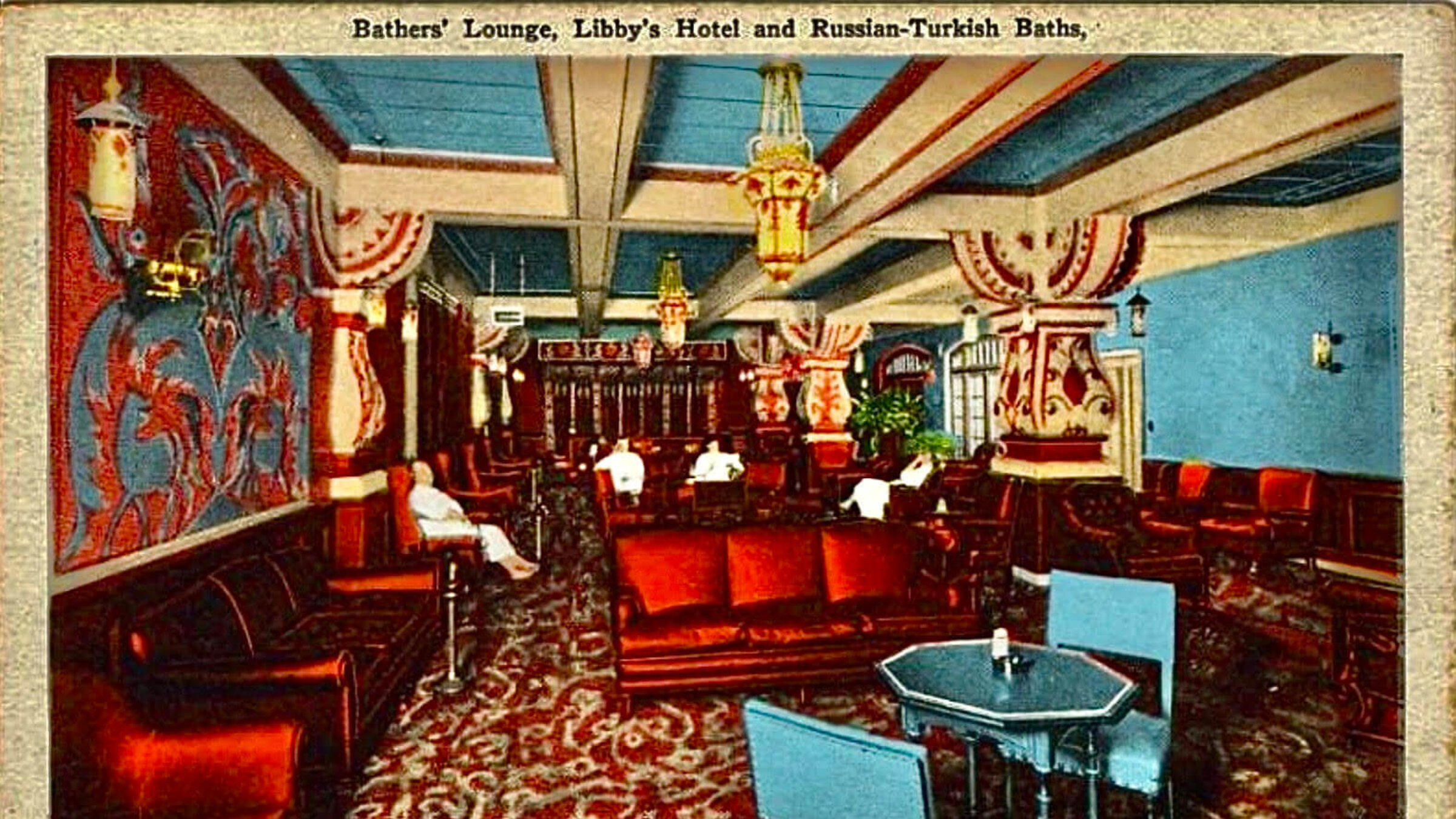

A postcard advertising the Libby Hotel on Delancey and Chrystie Streets, with the lounge of its Russian and Turkish baths Courtesy of Henry Sapoznik

The Tourist’s Guide To Lost Yiddish New York City

by Henry Sapoznik

State University of New York Press, 320 pages, $29.95

Henry Sapoznik’s superb new book, The Tourist’s Guide To Lost Yiddish New York City, is perhaps mistitled. It’s not really a tourist guide, but more like a cross between a yizkor book (a memorial book that documents Jewish life in a specific shtetl before the Holocaust) and a candy store.

David Petrusza’s recent book Gangsterland, for example, is a tourist guide. A look at crime in 1920’s New York, the book is organized by address; you can carry it with you and actually take a walking tour. “Oh, such-and-such crooked gambler was shot at this building; walk along a few more feet and that’s where they threw that stoolie off the roof; just around the corner was where Arnold Rothstein’s mistress lived…” and so on. You can’t do that with Sapoznik’s book because it’s not organized by neighborhood but by genre: Food, Architecture, Theater and Music.

Sapoznik writes about something that’s irretrievably lost, which is why it feels like a yizkor book.

Lost Yiddish New York City is one of a newly-developing (and long overdue) genre of books about vernacular Jewish culture, focusing on how ordinary people lived. (Eddy Portnoy’s Bad Rabbi, a collection of outré souvenirs from the Yiddish tabloids, is another.) It is not, thank God, an academic book, but rather a book for ordinary people who might be interested in learning how their ancestors walked, talked and lived.

What remains of the New York those ancestors lived in is very, very little: Yonah Schimmel’s Knishes; the B&H Dairy Restaurant; the imitation kosher delicatessen (“treyf from birth’’) Katz’s, and in altered forms — the Second Avenue Deli and the Forverts. The rest, as Hamlet said, is silence.

But this book is not silent. It’s more like a raucous Brooklyn candy store full of sweet delectations from New York’s vintage era. Sapoznik, a musician and musicologist who served as YIVO’s first sound archivist, once again shows his remarkable skill at unearthing delightful curios. With his former group Kapelye, the most entertaining of the 1980’s Klezmer revival bands, he recorded long-forgotten Yiddish pop gems like “Levine Mit Zayn Flying Machine” and Rubin Doctor’s elegy to chicken.” For NPR he developed and produced the excellent Yiddish Radio Project, perhaps the only NPR series released in a CD box set. He has also written two books on klezmer music.

Digging through over 5,000 Yiddish and English newspaper articles, he has assembled a catalogue of characters like Shmulka Bernstein, who not only ran the best shomer-shabbos deli in New York, but also pioneered kosher Chinese food and fake bacon; Sender Jarmulowsky, that rarest of all men — a beloved banker — famous for “lending money on character” (like his spiritual cousin A.P. Giannini, who founded The Bank of America and inspired one of Frank Capra’s best movies — why didn’t Yiddish theater do something like that for Jarmulowsky?); legendary rock ‘n’ roll impresario Bill Graham, a Yiddish-speaking Holocaust survivor who after their concerts at his Fillmore East (a former Yiddish theater) would treat bands to an onstage feast catered by Ratner’s Kosher Dairy Restaurant next door.

There are amazing stories like the literal rise and fall of Libby’s, the most spectacular hotel ever built on the Lower East Side, done in by — who else? — crooked real estate men; Dubrow’s crime-ridden Vegetarian Cafeteria on Eastern Parkway, where, on a Tuesday morning in 1938, a few dozen customers continued eating breakfast while four robbers carried a barely-covered 200 lb. safe full of cash and jewelry through the dining area and out the front door; and the time when the great Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson shared a night’s booking at a Romanian steak house with the one and only Boris Thomashefsky, the foundational figure of the American Yiddish theater.

Sapoznik is first and foremost a musicologist, and the section on music is loaded with color. The full story of the “Joe And Paul” song is here (in which the owner of the eponymous Stanton St. clothing store, horrified by the semi-obscene takeoff on his radio ad, sued the record company and won an out-of-court settlement.) You’ll also read everything you ever wanted to know about Yiddish comedian Benjamin Samberg, a.k.a. Benny Bell, whose English-language song “Shaving Cream” became the ultimate “Dr. Demento” record.

We learn about Apollo Records, a company that originally specialized in cantorial recordings, but switched to blues, jazz and gospel in the late 1930’s. When Bess Berman, the label’s then-owner, approached legendary singer Mahalia Jackson about cutting some gospel discs for Apollo, Jackson balked; she had never recorded her work, because she was reluctant to sing sacred music for a secular audience. “Well,” said Berman, “that’s where all the sinners are.” Jackson signed with Apollo.

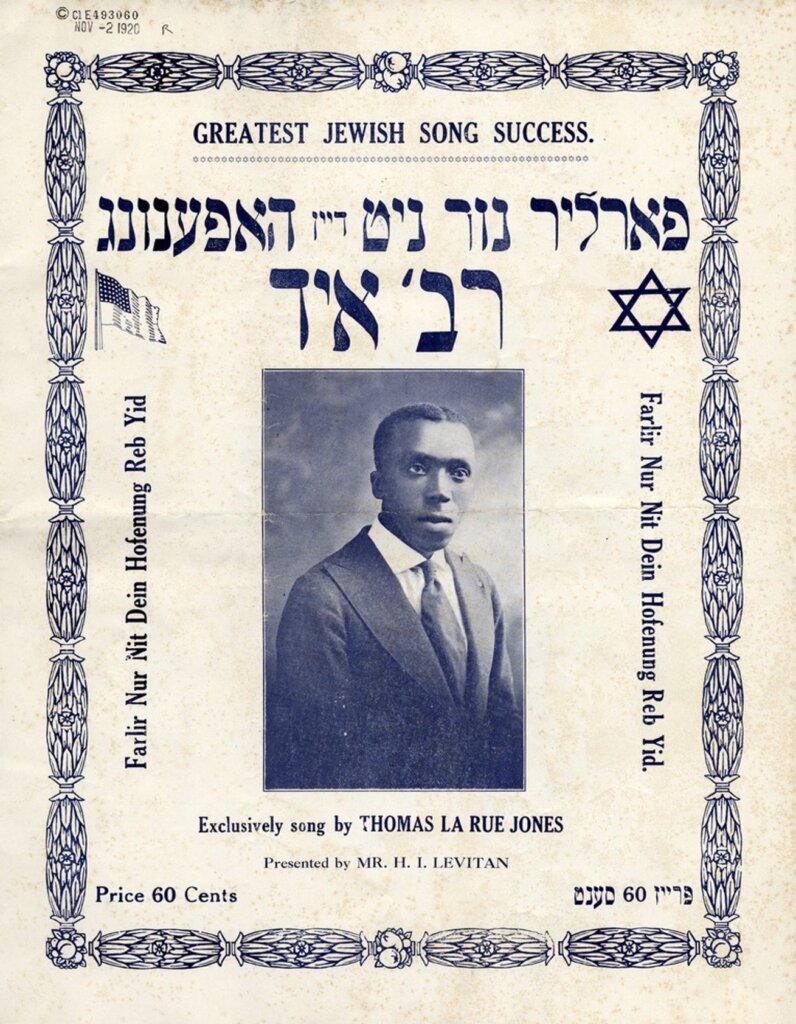

Jewish sacred music is covered extensively. There’s a fascinating chapter on khazntes (women who performed traditional cantorial music in secular spaces), and an even more interesting one on “Shvartse khazonim” (Black cantors), who were a sensation on the concert stage and in the Yiddish theater beginning in the 1920’s. The story of one such khazn, Thomas LaRue Jones, z”l, is especially moving.

One of the book’s many incidental pleasures is the way it constantly evokes a warmer era in Black-Jewish relations. Besides Jackson, LaRue Jones, ‘Bojangles’ and several others, the very cover of the book reproduces the famous 1953 photo of Brownsville’s Kishke King deli — and all the customers in the picture are African-American, which evokes a nostalgic we’re-all-in-this-together feeling.

The final section, on Yiddish theater, contains a marvelous piece about the hugely popular comedic character “Yente Telebende,” a nightmare shrewish yidene (mature Jewish woman) of countless humorous essays, records, and stage adaptations from 1913 until the early ’50’s. (The creators of Fiddler On The Roof used her first name, but pretty much nothing else, for their own comic creation — the matchmaker — who, like so much of the musical, has absolutely nothing to do with Sholem Aleichem.) And the very last chapter, appropriately enough, speaks to the absorption of “Yiddishland” into American life via the work that most perfectly encapsulates this: The Jazz Singer, which was written as a short story, turned into a Broadway play, made into a historic film and a host of misbegotten remakes.

I have a few minor criticisms. First, having the book organized by theme is not ideal. Fully the first third of it, for example, is about food. The entries are interesting, but after 104 pages of delicatessens, dairy restaurants, Romanian steak houses, and cafeterias, you start looking around for an Alka Seltzer.

There’s also an error in the book, which I am aware of for personal reasons. In a section on the Gilbert and Sullivan plays translated into Yiddish by Miriam Walowit, Sapoznik mentions the late Al Grand, who expanded Walowit’s one-act version of H.M.S. Pinafore into a full-length piece. Sapoznik mistakenly reports that Grand claimed credit for writing the whole thing. I knew Grand very well — I worked with him for years on his Yiddish version of The Pirates of Penzance — and he, a perfect gentleman, always credited Walowit for her part of the Pinafore adaptation. (Both Walowit and Grand are credited on the amateur recording released on CD in 1994.)

Finally, the book does suffer occasionally from something that plagues most current books put out by smaller presses. Because of the constricted conditions of today’s publishing world, you can’t help but notice the absence of a copy editor. Particularly in the later chapters there are a handful of syntactical errors that a good proofreader would have cleaned up.

This last is particularly regrettable because Sapoznik has such a delightful way with language. The appetizing seller Joel Russ, for example, who brought his daughters into the business because he had no sons, is called “a smoked-fish Tevye.” Herman Schildkraut, who ran a dairy restaurant specializing in meat substitutes, was “the poet laureate of meatless eats,” while his rhyming newspaper ads were “vegetarian hot doggerel.” I laughed out loud many times.

Sadly, there is no epilogue or coda of any kind. After the chapter on The Jazz Singer, the book does not end; it stops. Which is too bad. We’ve just spent 300+ pages in the company of an ace raconteur, who picks the best stories and tells them all beautifully. It would have been nice if he’d said goodbye before leaving.

But maybe Sapoznik has more to share with us? Count me in his audience if he does. Nitpicking aside, this is a wonderful book.