Opera about a unique Yiddish dictionary to have its world premiere

The plot involves two Jewish scholars determined to revitalize the language after its near destruction in the Holocaust

A concert performance of the opera held last year, without sets or costumes Photo by Steve Pisano

It’s not every day, even in New York City, that Yiddish enthusiasts can see a live, fully-staged performance of an opera about Yiddish.

But on September 18 and 21, “The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language” — composed by Pulitzer Prize finalist Alex Weiser with a libretto by Ben Kaplan — will come vividly to life on stage at YIVO. New Yorkers had the chance to enjoy a concert performance of the opera last year. But this staged version will be a different experience, with sets, costumes and effects created by lighting and digital projection. Most importantly, because GDYL is a chamber opera, with five singers and an instrumental ensemble featuring clarinet, string quintet and piano, the performances will likely feel more intimate and personal than with a full orchestra.

I spoke with Weiser and Kaplan, who helped me understand that “The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language” is a story about the intersection of scholarship with memory and grief. The setting is New York, one decade after the Holocaust. At the center of the drama is the Yiddish language itself. It has been terribly wounded, nearly murdered in the Holocaust along with millions of its speakers. Both main characters, distinguished linguists Yudel Mark and Max Weinreich, believe that a definitive all-Yiddish dictionary — authored by Mark and sponsored by Weinreich’s YIVO — will help revitalize the language they love. But each of them has his own unshakeable vision of what the dictionary should be like. Despite their long friendship and deep mutual respect, their visions for the dictionary prove incompatible.

In the opera, Mark is sung by lyric tenor Jason Weisinger. Weiser describes Mark as “a secular Jew who treats the Yiddish language with an almost religious fervor.” He sees each word as a “divine spark,” an idea taken from Kabbalah. He wants his dictionary to be a huge extravaganza in twelve volumes, celebrating Yiddish in all its amazing variety — the Yiddish equivalent of the Oxford English Dictionary. “In his mind, omitting words is a kind of sacrilege, especially after the Nazis have murdered the majority of Yiddish speakers,” Weiser said. Mark is hungry for words, eager to include every word ever spoken or written in Yiddish.

Weinreich is sung by baritone Gideon Dabi. “His approach to the dictionary is diametrically opposed to Mark’s,” said Kaplan. While Mark wants to include everything, Weinreich envisions a concise and streamlined dictionary in one volume — the Yiddish version of Webster’s. He’s also adamant about following YIVO’s strict rules of grammar and spelling, called the “Takones.” For Weinreich, rules and standards are essential to restoring Yiddish’s dignity, which was robbed by the Holocaust. Trying to capture every single “divine spark” will only cause chaos.

The other character in the opera isn’t a human being at all. It’s the letter aleph, the first letter of the Yiddish alphabet — a reference to the disappointing and almost absurd outcome of the dictionary project. Mark refused to follow Weinreich’s spelling rules or to limit his selection of words. He published four volumes on his own, without YIVO’s endorsement. And because he insisted on including every single Yiddish word beginning with the letter aleph, all four volumes covered only words beginning with the first letter of the alphabet.

The aleph character is sung by three mezzo-sopranos (Kristin Gornstein, Kelly Guerra, and Kate Maroney), personifying the three types of aleph used in Yiddish: the shtumer (silent) aleph, the pasekh aleph (pronounced “ah”) and the komets aleph (pronounced “oh”). The three alephs are mystical and ambiguous, sometimes even playing characters in YIVO’s offices. At other times they embody Mark’s “divine sparks,” interacting with him and commenting on his dreams for the dictionary.

The fully-staged version of “The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language” will have a whole new visual toolkit at its disposal to tell this unique story. Weiser is YIVO’s Director of Public Programs and Kaplan is Director of Education, so they have unlimited access to YIVO’s vast archives. For this opera about words, they wanted images of books and documents to predominate. But these images will be anything but straightforward.

Rebecca Miller Kratzer, the director of the staged production, gave me a taste of how the imagery will enhance the dream-like mood. “The singers will be engulfed by paper in different proportions and scales,” she said. She explained that some of the paper will be tangible and sculptural, part of the actual sets. But the staging will also use digital projections. The combination of physical and projected imagery will move the action between the scholarly world of books and card catalogs at YIVO, and the mystical world of the three alephs — the realm of memory and mourning, sometimes touched with a flicker of humor.

Kratzer also described researching historical Yiddish theater in New York City for the costumes and sets. “We want to go beyond images of Eastern European Jewry that are familiar to audiences from ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ and paintings by Marc Chagall. There’s a whole visual world of Yiddish theater that was born right here in New York, and we decided to mine that incredibly rich resource,” she said.

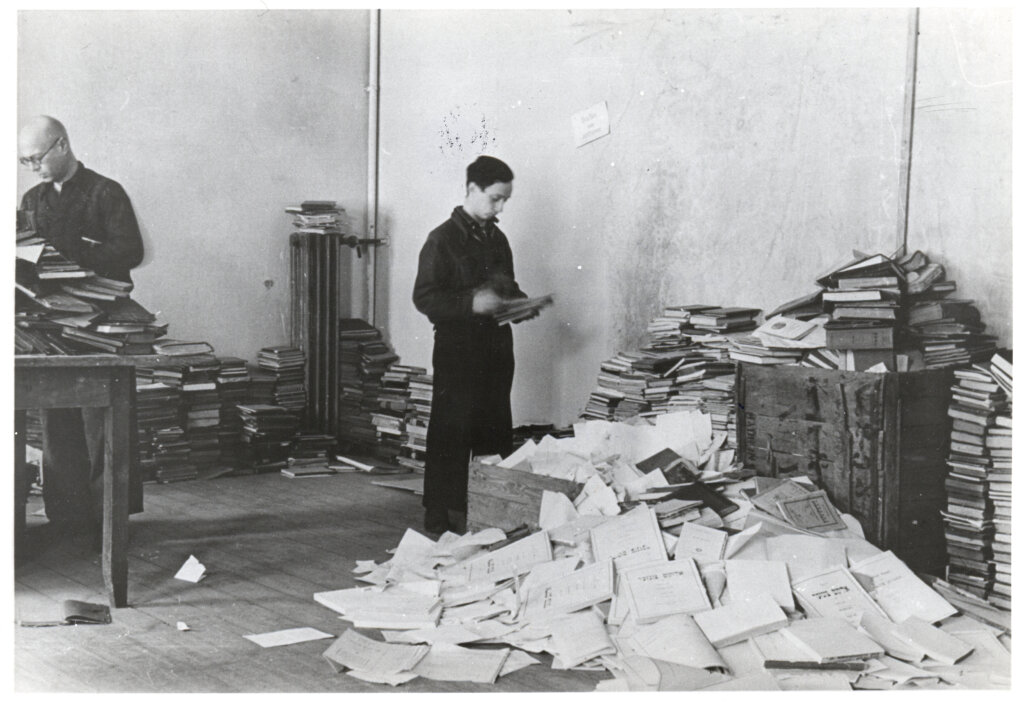

Weiser and Kaplan drew my attention to another important source of inspiration — historical images from the Vilna Paper Brigade, an extraordinary episode in YIVO’s history involving the rescue of Jewish books and documents from under the Nazi’s noses.

Kaplan pointed out that “The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language” is being performed as part of YIVO’s annual Nusakh Vilne event, which commemorates Vilna’s once-flourishing Jewish community (and also the 100th anniversary of YIVO’s founding in Vilna). “Remembering the Paper Brigade onstage feels deeply appropriate. It’s part of the same story as the Great Dictionary — rescuing Jewish written heritage from an attempt to wipe it off the earth,” Weiser said.

Audiences can see for themselves on September 18 and 21. Tickets to the performances are free, but must be reserved in advance. If you’re in New York, book now. No lover of Yiddish should miss this one-of-a-kind theatrical experience.