A glimpse of the Jewish left in 1920s Palestine

Hanan Ayalti’s Yiddish novel “Boom and Chains,” now in English, portrays the complex struggles of the Jewish pioneers

A settler plowing the land of Kibbutz Kiryat Anavim, in the Judean Hills, Nov. 30, 1920 Photo by Wikimedia Israel

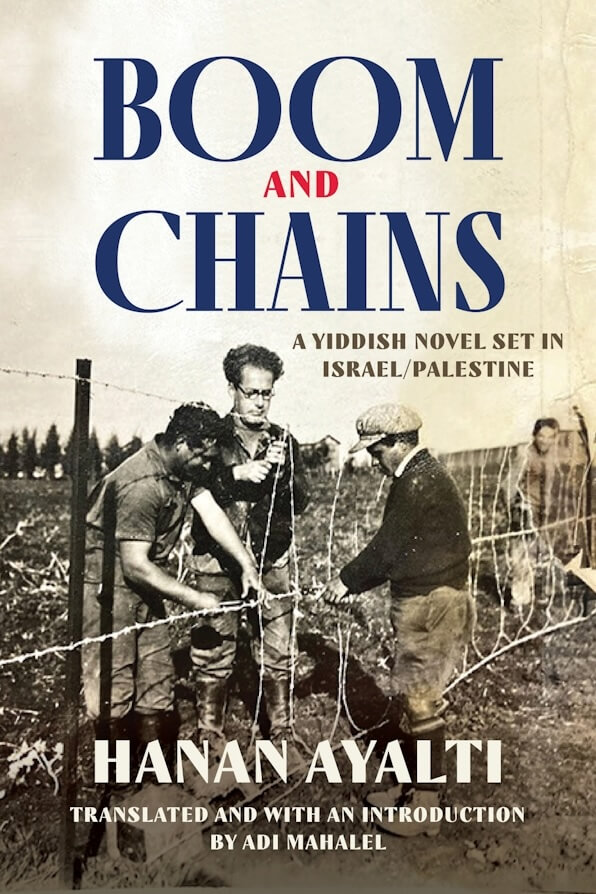

Boom and Chains

by Hanan Ayalti, translated by Adi Mahalel

Wayne State University Press, 312 pages, $34.99

Boom and Chains, by the Yiddish writer Hanan Ayalti, is a sweeping, morally urgent novel of Mandate-era Palestine that marries socialist ambition, Zionist dreams and the lived terrain of Arab dispossession.

First serialized in Warsaw in 1936 and now translated into English by Adi Mahalel, the book reads less like a period curiosity than a dispatch from the very core of 20th-century Jewish history. Its cadences are elegiac and insurgent at once, never letting the reader forget that every utopian project is built on contested soil.

In his introduction to the book, Mahalel frames Boom and Chains as both a reflection of Ayalti’s life and of the century’s ideological turns. “The evolution of Ayalti the writer clearly parallels that of his characters: from ‘good Hebrew Zionist pioneers’ to ‘active Yiddish resistors,’” he writes, noting that Ayalti’s passage from the kibbutz to antifascist Spain and then to Montevideo and New York marks a restless search for integrity within shattered utopias.

In Spain, Ayalti became an impassioned antifascist, crediting the USSR for defeating “both antisemitism and fascism.” Yet, as Mahalel observes, “his disillusionment with Soviet Communism actually began in Spain,” when he saw the Party’s betrayals firsthand. After fleeing occupied France in 1942, he rebuilt a quieter life in Uruguay and later New York, teaching Yiddish and editing the Yiddish labor Zionist publication Yidisher Kemfer, but, Mahalel notes, he often omitted Boom and Chains from his bibliography, having “renounced the novel out of ideological reasons.” Mahalel’s account transforms the novel from a historical curiosity into the record of a conscience in motion — a writer forever caught between belonging and critique.

The main narrative unfolds in three parts: “Kibbutz,” “Land and Work” and “God and Money.” These sections map not only the external struggles of settlement but also the inner fractures of its pioneers. When Zalmen, the central figure, lands in Jaffa, the novel enacts collision immediately — Arab boatmen unloading cargo, British officials announcing strikes, Jewish pioneers hammering tents into soggy terrain.

Every logistical failure becomes a metaphor: each collapsing tent points to the wider chasm between idealism and ground. The storm sequence in the early kibbutz chapters — especially “Lying in the Mud and Barking at the Moon,” where the settlement nearly washes away — dramatizes that elemental struggle. You feel the land itself resisting its would-be redeemers.

By the time the narrative moves into Part II, the Arab perspective emerges not as backdrop, but as voice. Mustafa, once a peripheral figure, becomes a frustrated agitator whose sermons — half economic, half prophetic — speak of debt, dignity and land. His words register with painful clarity, even if the pioneers cannot or will not hear them.

The 1929 riots arrive with terrible inevitability. In one of the most wrenching scenes, Moshe Milner, a Jewish pioneer from Poland, is beaten for trying to raise funds for both Jewish and Arab victims. Solidarity itself is punished. In moments like this, Ayalti insists that the reader confront the impossibility of innocence.

Part III takes the novel toward collapse. Ideological certainties falter, comrades turn on one another, and even the land that promised redemption becomes charged with betrayal.

Comrade Gamzu, part zealot and part tragic figure, embodies this unraveling. At one point, he sits in his office writing an article for the Hebrew socialist newspaper — a small moment that crystallizes the novel’s insight: Labor is fought not only in fields and factories, but in words. The stormy conclusion leaves characters battered and arrested, and gives readers the sense that history itself has not yet chosen its verdict.

Ayalti’s place in Yiddish literature is unusual. While contemporaries often looked back at the shtetl or outward to immigrant life, he brought Yiddish to the frontier of Palestine. The result is a language of tension, where sacred vocabulary intermingles with slogans of socialist struggle.

It’s a reminder that Yiddish was not only a vehicle for memory but also for imagining futures — even ones later suppressed. (After moving to the United States, Ayalti set the novel aside for years.) In its ambition, Boom and Chains recalls the scope of the Soviet-Yiddish writer Dovid Bergelson and the ideological searching of I. L. Peretz, but it’s more direct, more politically uncompromising.

The translation is mostly smooth, though a few idioms fall flatter than the Yiddish likely sounded. For instance, a phrase like “to break one’s back for the land” feels more awkward in English than the fierce irony it probably carried in the original. Still, the glossary is a gift: Terms like Shomrim (guards, or members of the Labor Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair) and shekhine — the Yiddish form of Shekhinah, the Divine Presence) — are defined in ways that illuminate not just vocabulary, but the ideals behind it. You can feel, even without direct citation, how carefully Mahalel has rebuilt the novel’s world for English readers.

One recurring weakness is that some characters lapse into long ideological speeches. Ayalti, at times, can’t resist the pamphleteer’s impulse. Yet even these stretches reveal the emotional urgency of an age when politics was lived from the trenches when the modern State of Israel was still years from being founded. The heaviness that results is, paradoxically, part of the book’s honesty.

What makes Boom and Chains remarkable is how current it still feels. The struggle over land and labor, the ethical crisis of building renewal at another’s expense, the oscillation between hope and despair — all of it reads less like distant history than like a mirror. The book refuses the easy consolation that redemption can be clean. Instead it presses its readers: No soil is free of debt, no vision immune to fracture.

For Jewish readers today, this translation is a gift. It restores a lost voice of Yiddish modernism and places before us a stark question: Can a dream of justice survive when its ground is contested from the start? Boom and Chains doesn’t settle the question, but it forces us to live with it. And perhaps that is the deepest service a novel can offer.