La Mort Que Je Conviens

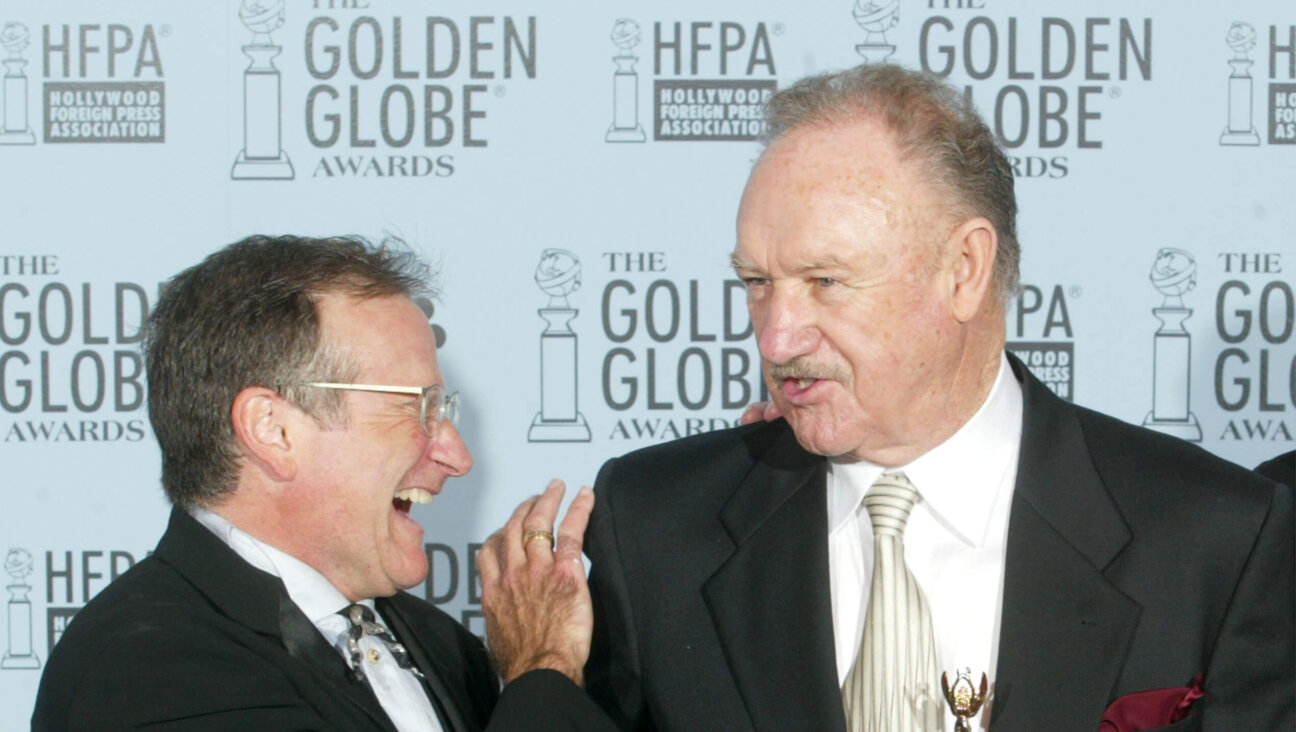

Before the waterfall: La femme sans tête lends a hand, even. Image by IMAGES COURTESY OF TWISTED SPOON PRESS

Ghérasim Luca was born in 1913 in Bucharest and, as a Jew and intellectuel, spoke Yiddish, Romanian, German and French, the last being the language of his books. A dissolute late adolescence found Luca traveling often through Paris, where he became interested in the movement called Surrealism. He spent the war hiding in Romania, which hated its Jews but occasionally sheltered them, too.

Hey doll face: Things are looking up. Image by IMAGES COURTESY OF TWISTED SPOON PRESS

Just before communism laid waste to Romanian independence, Luca founded the Romanian Surrealist Group with Gellu Naum, Paul Paun, Virgil Teodorescu and Dolfi Trost — names that should be as familiar as those of Europe’s privileged West: Aragon, Artaud, Baron, Bousquet, Boiffard, Carrive, Crevel, Desnos, Éluard and Ernst, the signatories of André Breton’s Le Manifeste du Surréalisme of the 1920s. In 1945, Luca and Trost collaborated on an Eastern responsa to France, “The Dialectics of the Dialectic,” which “concerns the need to maintain Surrealism in a continually revolutionary state.” Pace Luca/Trost: “This continually revolutionary state can only be maintained and developed by a dialectical position of permanent negation and of the negation of negation, a position which might be capable of the greatest imaginable extension towards everything and everyone.”

A self-professed étran-juif *— the author’s neologism, a “StranJew,” but strictly by birth; by affinity he was a libidinist and casual Satanist — Luca was not allowed to leave Romania until 1952, after a decade of persecution. He landed in Israel, only to turn around on the next boat for France, the country that he had, linguistically, never left. (Reportedly, Luca spoke no Hebrew and knew only one word in English — “elbow.”) His Paris colleagues were Jean/Hans Arp, François Di Dio and Paul Celan; his Parisian creations were bricolages, cubistic collages, automatic drawings and text installations. In 1994, the impoverished but legendary author was evicted from his apartment, officially for “hygienic reasons,” his housing complex slated for demolition. After having lived in Paris for 40 years without papers, Luca was now not only stateless, but also homeless; distraught, octogenarian, he drowned himself in the Seine, jumping off the same bridge, the Mirabeau, that Celan used for his own suicide two decades earlier: “La mort que je conviens comme une nécessité, comme la soupape du désespoir, comme une réplique de l’amour et de la haine, comme une prolongement de mon être à l’intérieur de ses propres contradictions*.” — “The death that I agree to be necessary — as a valve of despair, as a replica of love and hate, and as a continuance of my being within its own contradictions.”

“The Passive Vampire” was first published in French in Bucharest in 1945 by Les Éditions de l’Oubli, a press that didn’t exist but was purported by its self-publisher, Luca, to be headquartered and famous in Paris. It is a book of memoirs, of mnemonic parlor games and memory tricks (was that a woman holding up a chair? or a chair holding up a woman?), of oneirism and onanism. Indeed, there is an overflow of O’s here — that most open and obliging of vowels, voluble and oragenital.

Before the waterfall: La femme sans tête lends a hand, even. Image by IMAGES COURTESY OF TWISTED SPOON PRESS

The book’s first section is titled “The Objectively Offered Object,” comprising an illustrated guide to the creation of Surrealist objets d’art, known as OOOs, including “a starfish attached to a spoon,” “a ball with nails hammered into it,” “two objects resembling a pair of earrings” and “a glass tube, the number 7, and a flat spool.” Each is an Object Objectively Offered to an inamorata as a gift of affection, meant to replace the flowers and chocolates that have “virtually become the calling cards of disinterested love.” If bonbons and roses translate to traditional amorousness, then Luca’s starfish/spoon, a token intended for “V.” (a Parisian Surrealist painter with Romanian ties, Victor Brauner), translates not even to pure lust, but to lustfully pure perversion: “To attach the spoon to the starfish I used an axe, a nail, and a long thread. This all-too directly pederastic operation lasted almost an hour, during which time I became extremely annoyed.”

Luca presents “Hélène” (Elena Teodorescu, wife of poet Virgil Teodorescu) with his “Diurnal and Nocturnal Displacement”: “She liked the balls I had in my room, and she had expressed the desire to have one. This desire to possess one of the balls, which from the moment I found them I interpreted as symbolizing testicles, enchanted me.” In thanks, “H.” gave him “a partially clenched hand grasping the end of a light bulb, both of these placed on a piece of velvet,” symbolizing, apparently, “the castrating dish of Salomé.” Photographs of OOOs are featured throughout, taken by Brauner’s brother, Théodore, who was adept at framing both the complex oddness of the constructions themselves and the simple lines of their shadows.

Part two, the eponymous “Le Vampire Passif,” is a text not about Surrealism, but of it. Readers habituated to reading for sense should know that with Luca, words and sentences and entire paragraphs exist exclusively for purposes of atmosphere, or mood; that anti-meaning is, significantly, meaning, and that Surrealist plots tend to debauch their resolutions amid purple prose, alcohol and smoke. Magritte said that the pipe he painted was not a pipe, because it was only the painting of a pipe, and Freud once insisted that his own smokable of choice was, in fact, not a penis at all, that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. While reading Surrealist prose, it helps to keep the movement’s plastic arts in mind, particularly Duchamp’s readymades, and the canvases of Dalí and de Chirico, and also to remember that Luca and his contemporaries wrote during the early days of psychoanalysis (one thought: Visualizing images and thinking thoughts exterior to the text one is simultaneously reading might itself seem like a Surrealist enterprise). It helps, too, to be attentively skeptical of authorial self-seriousness, and receptive to excess, tangents, contradictions, contradicted contradictions and defensive flashes of humor.

The whole of Luca’s second part seems to be a convoluted carnal memoir of “Déline,” most probably a pseudonym for Nadine Krainik, who was a former lover of Paul Paun, and a future “Nadja” to easterly Surrealist cenacles in Paris (Nadja being the muse of Breton’s novel of the same name): “Déline. I sit beside Déline, I stroke Déline, I kiss Déline, I leave with Déline, I make love to Déline.” After dozens of dense pages concerning bats and winged goats and waxwork dolls and “a sperm of silk or sulfur,” the reader is left with a confession: Lust sustained can turn to LOVE (the capitals, as always, are Luca’s; Fijałkowski’s translation is sympathetic).

Toward section’s end, the Lucan narrator, a sort of layabout Dracula, reminisces, and, in this reminiscence, autobiography is confirmed: “The nine days of love during which my freedom had exceeded even the hopes I placed in poetry and revolution, a limitless, total, infernal freedom, seem to me the mirror reverse of the nine days I spent in prison nine years earlier because of love, because of my poems about love that my contemporaries had cited in their legal briefs as a case of the assault on common decency. From this battle between the demon of freedom and the god of prison there emerged, as if to justify my delirium of interpretation, the obsessive number 9, designated by the calculations of the black Kabbalah as an entirely analytical number and, all-powerful beneath its crystal cape, with its comet’s red eye, there also emerged LOVE, mad and lucid, real and virtual, living and dead like Déline’s hair. As Déline, the indecipherable ghost of love, fell asleep on my shoulder she darkened the darkness.”

Invoking “the god of prison,” Luca refers to his short sentence for offending morality, the punishment for sending editions of his erotic poetry to officials of the Romanian government in 1933. That auto-destruction, typical of Luca, was also the essence of the Surrealist project in its Eastern iteration. The artful fracturing of bourgeois French reality became, in a much more politically volatile and sexually repressive milieu, the frantic Othering of the creative self. In Bucharest, especially after the war, there was nothing else left to corrupt.

Joshua Cohen’s most recent novel is “A Heaven of Others”(Starcherone Books, 2008).

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO