Pakistani Rock Star Builds Cultural Bridges

A Doctor, and a Legend: Salman Ahmad, South Asia?s biggest music celebrity, performs in India (above) and teaches at Queens College. Image by GETTY IMAGES

Salman Ahmad, M.D., knows that he is an unlikely rock star.

Make that an unlikely rock star, klezmer jam-session collaborator, celebrity to the Muslim world and United Nations goodwill ambassador.

Not bad for a kid from the suburbs of New York who earned his medical degree to please his parents.

“I should not be doing this, but some force steered me in this direction,” he said, laughing with the air of someone still startled by his good fortune. “I see myself as an instrument, I really do.”

Ahmad, 45, is a huge celebrity throughout South Asia, including in his native Pakistan, where he basically created the genre of Muslim rock music. He and his band, Junoon, which mixes hard rock with Sufi poetry and devotional music, have sold more than 25 million albums worldwide. They’ve been compared to U2, and inspire Beatlemania-level hysteria among fans. But recently, Ahmad’s been reaching out to a new audience: American kids who think “Muslim rock” is an oxymoron.

He teaches a class on Muslim music and culture at Queens College in New York: It’s as if Bono dropped in regularly to lecture undergraduates on Gaelic songwriting. And Ahmad collaborates with renowned klezmer artist Yale Strom on a Queens program called Common Chords, a musical project dedicated to creating harmony, literally and figuratively, among different religions and ethnicities.

“He’s a joy to work with,” Strom told the Forward. “I wish I could say I’ve sold 25 million CDs like he has, but he doesn’t come into a room and say, ‘I’m Salman Ahmad, and I played at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony.’ He’s a very humble person.”

Coolest Prof Ever: Ahmad, shown performing in 2006, teaches at Queens College. Image by JuNOON.COM

Ahmad started teaching at Queens College and playing with Common Chords after running into history professor Mark Rosenblum, director of the Queens College Center for Jewish Studies and the Michael Harrington Center for Democratic Values and Social Change. They literally bumped into each other after Ahmad spoke at a Clinton Global Initiative event. At the time of their collision, Ahmad was fasting for Ramadan, and Rosenblum was fasting for Yom Kippur, so they avoided the buffet together and struck up a conversation, during which Rosenblum made his pitch for Ahmad to come talk to Queens College students.

One appearance turned into a semester of teaching; Ahmad liked it so much, he decided to continue.

“There’s no doubt he’s a legend, and he has groupies who come to his classes,” Rosenblum said, but he stressed that Ahmad isn’t just coasting on his fame. “He’s a key player among religious Muslims engaged against what they see as a hijacking of their religion by violent factions…. He’s fully engaged in the cultural struggle. He’s a great soul who is very, very charismatic. I think he’s got the capacity to teach and to learn, which is rare.”

Born in Lahore, Pakistan, Ahmad moved with his family to the idyllic village of Tappan, N.Y., when he was 11 and spent his formative teenage years there. He vividly remembers his first concert, Led Zeppelin at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. When he saw Jimmy Page wailing on a double-necked guitar, special effects smoke curling around the dragons painted on his trousers, the young Ahmad found his calling.

“It was a transformational experience,” he said. “I decided I definitely wanted to be a guitar player.”

He formed a band with his friends. But his parents were equally certain that he should go to medical school and become a doctor. So he did, obtaining his medical degree in Pakistan, all the while continuing to play guitar. The military dictatorship then ruling Pakistan had banned rock music, so Ahmad and his friends pioneered an underground scene.

“I realized music was the only form of expression we had,” Ahmad said. “I became a doctor and I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to play music for one year.’ That year hasn’t ended.”

The conditions in Pakistan now remind him of his oppressive student days. While the government no longer tries to repress music, Taliban forces surging in the Swat valley district of northwestern Pakistan are threatening freedoms, artistic and otherwise.

In 2003, Ahmad starred in a Public Broadcasting Service documentary called “The Rock Star and the Mullahs,” which featured him playing music in Pakistan and debating local hard-line Islamic leaders about the legitimacy of Muslim music. More recently, a disturbing cell phone video of Taliban fighters flogging a teenage girl, allegedly for being seen with a man who was not her husband, prompted Ahmad to return to Pakistan and organize anti-Taliban rallies and concerts.

“Something snapped in my head,” Ahmad said. “Those events, I’ve got to keep on doing.… The Taliban are again trying to impose their extremism on a country of 170 million people who love music.”

He moved back to Tappan after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks because, he said, he wanted to reconnect with America: “The only way I know how to do that is to play music and meet people.” He toured college campuses across the country and connected with Queens College and the Common Chords program. Sometimes it seems as though he makes a case with high school and college students similar to the one he makes with the Taliban, trying to persuade people that Islam has a proud tradition of music that should be celebrated.

“People ask, ‘How can you be a rock musician and a Muslim?’” Ahmad said. His answer: “Look, we’re making this up as we go along.”

Ahmad said his current musical style is rooted in Qawwali, the traditional Sufi devotional music, fused with the classic rock of Led Zeppelin, the Beatles and Santana that he loved in his youth, and seasoned with a healthy dose of Bollywood inspiration.

Both he and Strom have been pleasantly surprised to discover the deep interconnectedness of Muslim and Jewish music, as each improvises on the other’s songs.

“The scales — that was a revelation for me,” Ahmad said. “The phrasing, the notes and the spirit behind them are just so similar.”

“There are certain keys that lend themselves, certain rhythms,” Strom agreed. “Even more than musically, it’s the feeling and the spirit that unifies us. Music creates a bridge to hopefully forge better understanding and mutual respect between Jews and Muslims.”

So far, it seems to be working. As part of his Middle Eastern studies program, Rosenblum asks students to role-play their “opposite”: A Jewish student would have to put himself in the shoes of a Palestinian nationalist, for instance, while a Muslim student argues the case of an Israeli settler. That can be a tough sell. But Rosenblum said he found it gets easier if the students have participated in a Common Chords concert beforehand.

“Let’s not talk about Palestinian nationalism right away; first, let’s talk about this music,” Rosenblum said. “The cultural dimension of an interfaith dialogue turns out to be easier.”

Ahmad is looking forward to his next semester of teaching at Queens College, and will keep busy this summer by trying to organize a huge concert at the U.N. in August to benefit the 3 million people who have been displaced by fighting in Pakistan. Ahmad is hoping to get fellow goodwill ambassador Angelina Jolie to attend (he’s been spending a lot of time on the phone with her people). He’s also got a book, “Rock & Roll Jihad” (“a misunderstood word that the extremists have hijacked,” he explained), and a new Junoon album coming out early next year.

Friends in Pakistan often urge him to return and run for political office — his star power would make the campaign a cakewalk. But the spell that Page cast some 30 years ago is still going strong: Ahmad is sticking with his guitar.

“I think that today, social movements are the way to bring long-lasting change,” Ahmad said. “I’m trying to give young people hope…. Pop culture can drive politics.”

Contact Rebecca Dube at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

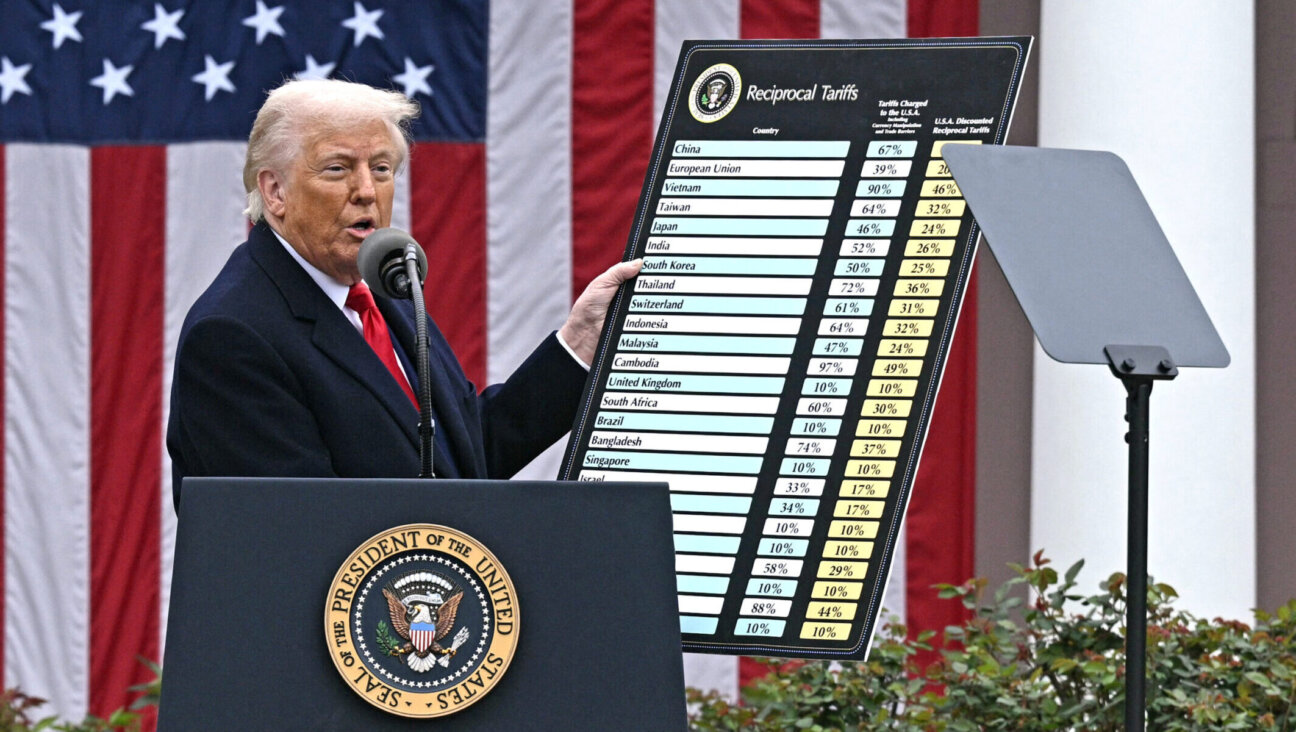

Fast Forward Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ includes 17% tariffs on Israeli imports, even as Israel cancels tariffs on US goods

-

Fast Forward Hillel CEO says he shares ‘concerns’ over campus deportations, calls for due process

-

Fast Forward Jewish Princeton student accused of assault at protest last year is found not guilty

-

News ‘Qatargate’ and the web of huge scandals rocking Israel, explained

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.