Peruvian Town’s Health Goes Up in Smoke

As far as Peruvian Rabbi Elias Szczytnicki could tell, Ira Rennert seemed like a guy with whom he could develop a rapport. Rennert, a controversial Orthodox billionaire, has served as chairman of the tony Fifth Avenue Synagogue in Manhattan and has been described by Elie Wiesel as “a deeply, deeply religious man.” But while on a mission to meet the reclusive Rennert in New York earlier this month, Szczytnicki quickly found out that there are limits to the faith that binds the two.

The Lima-based rabbi came to town as part of an ecumenical delegation to urge the Brooklyn-born billionaire to curb the massive health and environmental damages being caused by a giant Rennert-owned smelter in Peru. Rennert, whose Renco Group holding company owns the plant in the mountain town of La Oroya, refused a meeting, telling them to deal instead with the company’s local subsidiary.

Szczytnicki and his ecumenical delegation are far from the first to protest Rennert’s business practices, nor are they the first to be turned away. But buoyed by tighter regulation in the United States of a man whom Hillary Clinton once labeled “the biggest polluter in America,” the Peruvians are stepping up the fight to clean up La Oroya.

“I understand he runs a business, but this is not just any kind of business,” Szczytnicki told the Forward last month. “It has lethal consequences on the lives of people.”

Unlike most disputes over the environmental impact of multinational corporations on impoverished communities, this battle revolves not around the extent of contamination — on which there is broad agreement — but around the responsibility for cleaning it up. That there is consensus on the need to address the smelter’s impact on La Oroya is due in part to a series of health studies, as well as a legal and regulatory battle involving a similar Rennert-owned plant in Missouri during the 1990s, as a result of which he was forced to adopt stringent anti-pollution measures and pay tens of millions of dollars in cleanup and relocation.

Smoke, dust and contamination have long been part of the air in La Oroya, a town of 33,000 perched 12,000 feet up in Peru’s mountainous Huancayo region. Primarily because of the smelter, which is owned by the Renco-controlled Doe Run Company, La Oroya bears the dubious distinction of being among the 10 most polluted cities in the world, according to the environmental advocacy group Blacksmith Institute.

A large number of environmental and health studies conducted by Doe Run, the Peruvian government and independent experts, among them the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have shown that inhabitants of La Oroya suffer from a number of illnesses caused by the emissions from the smelter’s giant smokestacks. Ninety-nine percent of children under age 6 have an unusually high level of lead in their blood, as well as high levels of cadmium, arsenic and sulfur dioxide, according to Doe Run and the Peruvian government.

When Doe Run purchased the plant from a Peruvian government-controlled company in 1997, it committed itself to a 10-year, $120 million plan to address the contamination of La Oroya. Since then, however, it has not implemented all the measures of the plan.

After prolonged discussions between the government and the company, the authorities eventually granted a three-year extension

Environmental and religious activists have charged the authorities with surrendering the well-being of the town’s citizens in order to protect a major source of income. The government has responded that it is trying to find a compromise between preserving jobs and improving the situation in La Oroya. The powerful mining labor unions, the government has noted, strongly opposed the idea of closing the facility, which employs some 4,000 workers and is the center of La Oroya’s economy.

“For us, it is difficult to denounce because we don’t want to be seen as destroying a source of revenue for the poor,” Szczytnicki said. “The Peruvian government is enforcing environmental and health regulations with a very low threshold in order to keep foreign investment in the country, especially in the mining industry.”

Last April, Doe Run announced that emissions from the plant’s main smokestack of particulate matter and heavy metals, including lead, had decreased to a level within Peruvian governmental limits. The company also stated that to date it had invested $116 million in environmental improvements, and it expects that by 2009, the total will reach $254 — more than twice the amount pledged in 1997.

The company’s announcement, however, did little to mollify its critics.

“They did not do the heavy investments; they preferred to provide assistance to the population,” said Rafael Goto Silva, a pastor who is president of the National Evangelical Council of Peru and a member of the ecumenical delegation that traveled to New York last month to meet with Rennert. “They invested in curing the symptoms, not the causes…. They have not done the hard part until now. Who can say they will do it in the next three years?”

Rennert, who is a generous donor to Orthodox causes in the U.S. and in Israel, did not respond to requests for comment.

For years, the company has argued that that the low prices of metals have resulted in less investment across the board and that most of the plant’s revenues have been used to pay back loans. A study commissioned by the Peruvian government, however, concluded that Doe Run could have completed its cleanup program in 2005 had Renco not taken an estimated $100 million from the Peruvian company between 1997 and 2004.

A pattern of maneuvering financial assets among a series of companies controlled by Rennert was one of the main reasons that the U.S. Justice Department filed a $900 million complaint against Renco, accusing it of siphoning off money that should have been used to clean up environmental damages caused by a giant magnesium plant in Utah. Those fighting to hold the corporation accountable for the Doe Run smelter’s impact on La Oroya have taken note of the precedent. With the rebound of the price of lead and other raw metals, they say, it is time for Renco to pay the price for its pollution.

“The company now has the money, and says it will fulfill its obligations,” Szczytnicki said. “But the record shows that they have only done so when confronted with pressure from government and local authorities…this is about the globalization of ethical solidarity.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

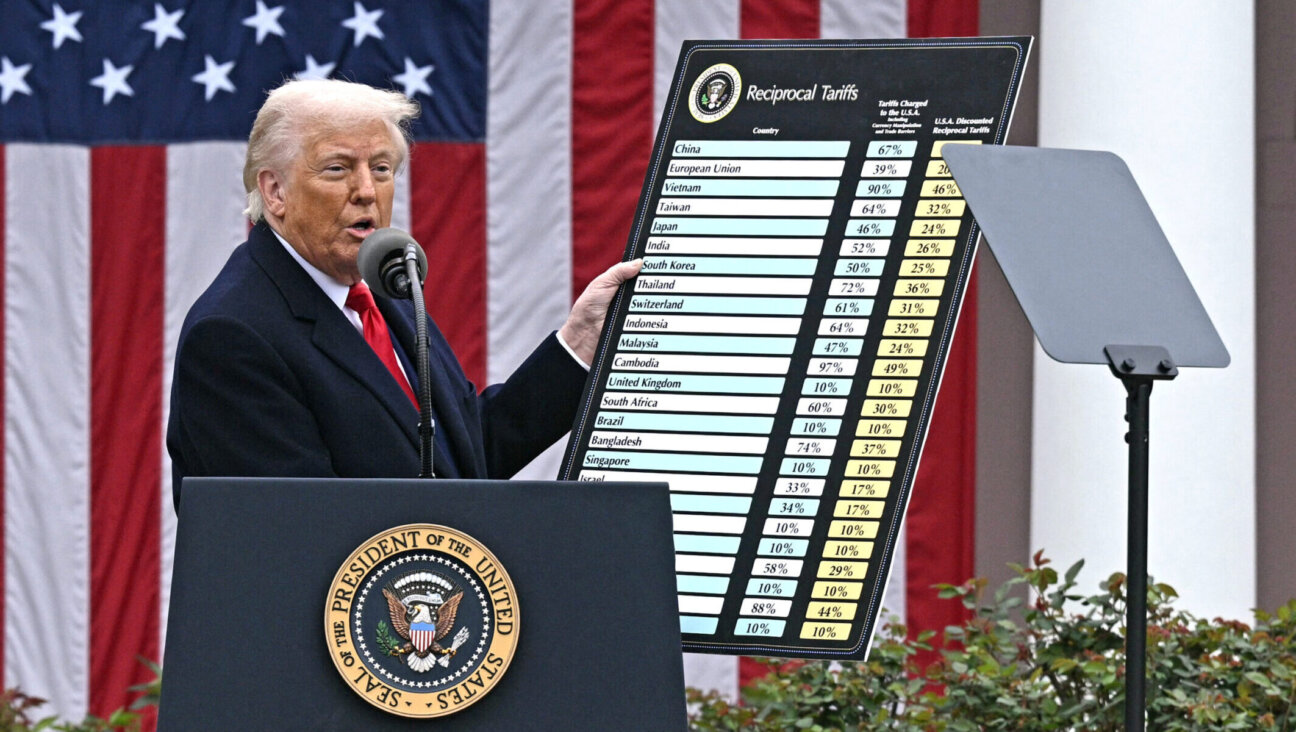

Fast Forward Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ includes 17% tariffs on Israeli imports, even as Israel cancels tariffs on US goods

-

Fast Forward Hillel CEO says he shares ‘concerns’ over campus deportations, calls for due process

-

Fast Forward Jewish Princeton student accused of assault at protest last year is found not guilty

-

News ‘Qatargate’ and the web of huge scandals rocking Israel, explained

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.