Love Is Not Blindness

Since the publication of “How I’m Losing My Love for Israel,” a personal essay describing my fatigue as a liberal Zionist, the most disturbing responses have not been the vitriolic e-mails or online comments, nor the thoughtful and well-reasoned replies from the likes of Daniel Gordis and Jonathan Sarna. Rather, I have been most troubled by the statements of many Jewish professionals — rabbis, federation leaders, nonprofit directors — who have told me, “Thank you for saying what I cannot.”

Why is it that they cannot say what I said? Because they fear for their jobs, or fear their organizations would be harmed if they expressed their opinion? And what opinion is that, which they and I share? Is it hatred of Israel? Support for the terrorists of Hamas? No. It is *ambivalence.

Remarkably, and disturbingly, this American Jewish McCarthyism has reached such a paranoid pitch that my colleagues in the Jewish world fear even to express ambivalence, uncertainty or reservation regarding the State of Israel. We fear that we might endanger relationships with members, donors, supporters and friends for expressing uncertainty. This is outrageous, and it has shocked me in the weeks since the column was published.

And to be clear, losing love does not mean lacking it. My colleagues and I continue to love Israel, support it and defend it against its enemies. What has changed is that they, and I, are increasingly of the opinion that Israel does not deserve the kind of love — unconditional, unwavering — that many in our community demand. This is so, not because we are unfaithful, but because our lover has become abusive.

For example, if, as Gordis writes, “Only justice matters. Only the future matters,” then we must ask some hard questions. What is the “justice” of expanding settlements? What kind of “future” do such policies augur for building a secure Israel and a viable Palestine? Those of us who question such actions don’t lack love of the Land of Israel or the State of Israel. But we are tired of having our love abused, yoked to violence and demanded of us as some kind of loyalty oath to the Jewish people. There is such a thing as too much forgiveness.

Nor is our concern because, as Gordis and Sarna both suggested, our love is somehow immature — it’s precisely because it is mature. Mature love does not mean total acceptance. It does not demand that we never visit the territories to see firsthand what is happening on the ground, or that we never fear for the demographic extinction of liberal Israel, or never criticize its growing wealth gap. We’re not naïve about the fact that many in the Arab world seek Israel’s destruction, by increments if not all at once. On the contrary, we want Israel to survive, to thrive, and not to sell its ethical and political birthrights for the porridges of territory and a dream that can never come to pass.

Fortunately, I think the American Jewish community is at a tipping point on these issues. The very ambivalence I described in my essay is the foundation of a new political movement, which coincidentally is about to hold its first conference in Washington. And I think one reason my little personal essay struck such a chord is that, between J Street, President Obama and these shifts in the American Jewish community, there’s an understanding that the tide has begun to turn.

Many find these changes fearful, which, I think, is why so many people responded with fear to what I had to say. But if you love Israel, you should celebrate these developments. Fewer and fewer people — especially American Jews under 40 — feel the reflexive, unquestioning loyalty that an older generation did. If their only choices were blind acceptance or outright opposition, they might just walk away. J Street and organizations like it represent a third way — and that is a very good thing for Israel.

Indeed, the more you love Israel, the more you should fear the loyalty oaths some American Jews demand. Such all-or-nothing binarism will drive our children away in droves. It will fail to convince anyone not already converted. And it will further marginalize the Jewish state, further remove it from dialogue, engagement and international cooperation. The all-or-nothing crowd in America is really just the flipside of the boycott-Israel crowd in Europe. Both oversimplify a complex situation, both see Israel and Palestine in terms of black and white, and in so doing, both are hurting the Jewish state.

If there is one thing I wish I’d done differently in my essay, it is that I should have mentioned exhaustion last, rather than first. It’s not that I’m

exhausted, and therefore rue the loss of Israeli values, critique American Jewish myth-making and question my own Zionist education. It’s the other way around. I loathe the company we Zionists are forced to keep: ethnocentrists, know-nothings, warmongers and worse; that angry pseudo-majority whose Disney-fied myths eclipse the region’s messy realities, who dehumanize Arabs and furiously lob the words “antisemitism” and “Holocaust” like rhetorical hand grenades. What they love is not what I love.

Yet I feel tainted by the association. Perhaps I would put up with the tiring defense of yet another Israeli trespass, the eclipse of the Israel I love by one I hardly recognize, and the companionship of those I mistrust if I didn’t mistrust myself as well. I, too, love Israel; I, too, was raised on its myths — and thus I am obligated to second-guess how I reflect upon its policies. Precisely because I hold love in my heart, I question my opinions, pause before jumping to conclusions, and doubt my intuitions of certainty.

It is this introspection, or perhaps its results, that has caused such a stir. Admittedly, it is less romantic than the swell of “Hatikvah,” less useful for advertising or propaganda. Yet sometimes true love looks very different from romance, and sometimes “yes” is not what a lover needs to hear.

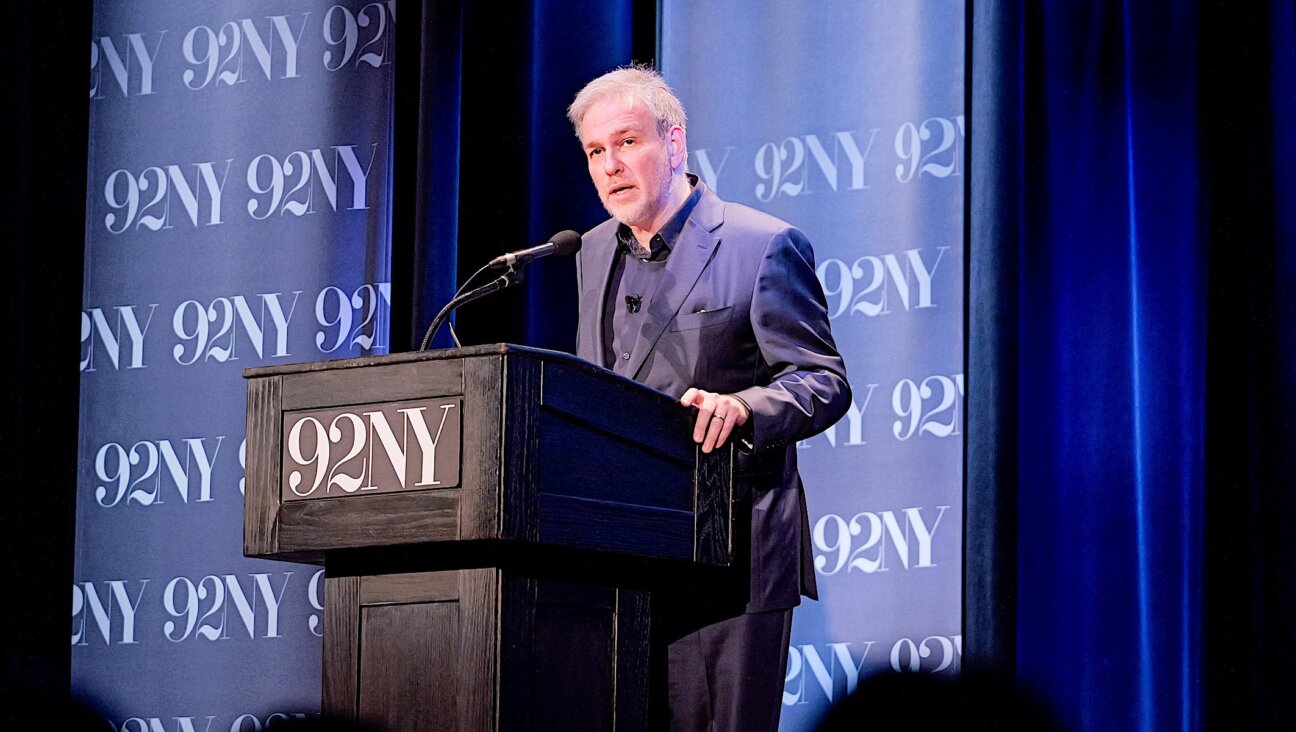

Jay Michaelson’s column, “The Polymath,” is published monthly in the Forward’s Arts & Culture section. He is the author, most recently, of “Everything Is God: The Radical Path of Nondual Judaism” (Trumpeter).

Read responses from Miriam Shaviv, Gadi Taub, Jonathan Tobin and Steven Zipperstein to the issues raised by Michaelson’s original essay, “How I’m Losing My Love for Israel,” here.