Raiding the Archive: Bringing Klezmer to the Masses Once Again

Serious Singers: The Cantors, Choristers and Ministers Guild sit for a picture in, or around, 1903. Image by Courtesy JSP Records

It’s a truism of traditional music that in order to go forward, you have to go back. To innovate on old material, you have to know the old material in the first place.

But in the case of Yiddish music, there’s often not much to go back to. During the heyday of Yiddish culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, klezmer melodies, Yiddish theater tunes and cantorial music were popular entertainments for Jews from Warsaw to New York. But with the Holocaust in Europe and the rapid assimilation of Jewish immigrants in America, that culture went away as quickly as it had come. For musicians today who want to learn the Yiddish repertoire, finding a living link to that centuries-old musical tradition is nearly impossible.

But there is another way. Between 1898 and 1942, some 6,000 78-rpm recordings of Jewish music were produced in the United States, and some 5,000 in Europe. When Jewish musicians in the 1970s revived the Yiddish music that had largely disappeared after the Second World War, it was to those recordings that they turned.

“If it weren’t for these historic recordings, there wouldn’t have been a klezmer revival,” said producer Henry Sapoznik, executive director of Living Traditions, a Yiddish arts organization that produces the annual weeklong KlezKamp in Kerhonkson, N.Y. “Of every traditional music scene, whether it’s Balkan or Greek or blues or early jazz, the only one that relied completely on using 78s as a style and repertoire model was the klezmer scene.”

“Cantors, Klezmorim and Crooners 1905–1953: Classic Yiddish 78s From the Mayrent Collection,” a new three-CD boxed set, expands both the quantity and variety of archival Yiddish recordings available to seasoned musicians and casual listeners alike. The release of the collection by Living Traditions and JSP Records celebrates the 25th anniversary of KlezKamp, which ran in 2009 from December 23 to December 29. In keeping with the practical function of these recordings, they were incorporated into KlezKamp’s many instructional workshops.

“Cantors, Klezmorim and Crooners” is not the first remastered collection of Yiddish music, but it is one of the most ambitious. For years, musicians have struggled to gain access to old Yiddish records. Those that weren’t junked or relegated to unknown attics were mostly held in institutional collections that restricted access to academic researchers, excluding both working and amateur musicians. Even for those who could get access, using the delicate and irreplaceable 78s for casual practice was impractical, and the much-coveted tape-recorded transfers that existed were of poor quality and further deteriorated with each new copy.

In the past few decades, however, music archivists and producers such as Sapoznik have begun remastering and releasing some of that material on CD and in other digital formats, making it available to anyone who wants it. To date, however, the bulk of the reissued material has been instrumental music, passing over equally prominent genres such as Yiddish theater and cantorial music. Additionally, much of the reissued material is repeated on several albums, leaving the vast majority of the original 78s untouched.

In both of these respects, “Cantors, Klezmorim and Crooners” breaks new ground. The collection got started in 2004, when Sherry Mayrent, a klezmer clarinetist and the associate director of Living Traditions, bought 100 Jewish 78s for $40 on eBay Inc. Mayrent got hooked on collecting, and now she owns more than 5,000 discs — the largest private collection of Yiddish 78s in the world. With the partnership of Sapoznik and Grammy Award-winning engineer Christopher King, Mayrent used her collection to create the new 67-track CD set.

“I had a dream that I would be able to make this stuff available,” she told the Forward. “The fact is that I’ve never heard any Yiddish recording of any quality that I haven’t learned something from.”

The collection encompasses a wide range of styles and genres that seem somewhat haphazard at first listen. On the first disc, an operatic performance of “Kol Nidre” by Cantor Selmar Cerini — one of the first cantors to make Jewish liturgical music a quasi-operatic art form — is immediately followed by a performance of “Katinka” by Yiddish theater star Molly Picon. But according to Sapoznik, it is precisely these juxtapositions that make this set valuable.

“It reinforces the interrelationship of one genre to another,” he said. “You get a chance to hear klezmer elements in cantorial singing, or cantorial phrasings in Yiddish theater songs. There was a lot of stuff that was obvious and clear to the original consumers of these records, which is not as clear today, which is why we used this kind of sequencing.”

The result is a collection that is both canonical and idiosyncratic, that both serves as an introduction to the uninitiated and presents new material for those who think they’ve heard it all. Tunes played by such legendary klezmer musicians as Naftule Brandwein, Dave Tarras and Abe Schwartz are presented alongside such obscure and forgotten artists as the Russisch-Judische Orchestra, a group whose recordings were imported from Europe by Columbia Records prior to World War I, though nothing is known about it outside of a single entry in a 1914 record catalog.

Other gems in the collection include a performance by Cantor Alter Yechiel Karniol in the zogekhts (speaking) 19th-century cantorial style, which, Sapoznik writes in his notes, is one of a few tracks that “cross the line between the commercial studio recordings they are and the field recordings they sound like.” Another rarity is a recording from 1915 of writer Sholom Aleichem reading “If I Were a Rothschild.”

“Reading a few lines from ‘Ven Ikh Bin Rotshild’ he stops,” Sapoznik writes, “prompting the engineer to call out ‘Is that all you got?’… Ten months later Sholom Aleichem died. When his funeral attracted a staggering 500,000 people, [RCA] Victor hurriedly rushed out the failed test record. When it did not sell it was soon dropped from the catalog, making the record one of the most important and rarest of all Yiddish commercial recordings.”

For all the material contained on “Cantors, Klezmorim and Crooners,” however, the CDs barely scratch the surface of Mayrent’s collection, which is why she plans to continue to remaster the records and release them all online.

A step in this process will be the recently-announced foundation of the Mayrent Institute for Yiddish Culture to be permanently located on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Sapoznik will head the new institute which will be dedicated to helping understand the world of Yiddish through its arts.

Extensive music projects are also being pursued elsewhere. Florida Atlantic University’s Judaica Sound Archives has been collecting Jewish music of all kinds since 2002, and provides much of it in streaming format on its Web site and more through research stations located in libraries throughout the United States, Canada, Israel and the United Kingdom.

These projects, however, have to contend with copyright laws which protect any recordings made after 1923. But Sapoznik is optimistic that they will eventually be able to release all of the material, much of which is now owned by such corporations as Bertelsmann and Sony.

“I think the tide is turning,” Sapoznik said. “It is sort of ironic that the Germans and Japanese own almost all recordings made in America prior to World War II — for the American people not to have access to their own national sound heritage. But I’m very optimistic that this is going to change.”

In the meantime, however, “Cantors, Klezmorim and Crooners” provides unprecedented access to a world and a musical tradition well worth holding onto.

Ezra Glinter is the books editor of Zeek: A Jewish Journal of Thought and Culture.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

Film & TV In ‘The Rehearsal,’ Nathan Fielder fights the removal of his Holocaust fashion episode

-

Fast Forward AJC, USC Shoah Foundation announce partnership to document antisemitism since World War II

-

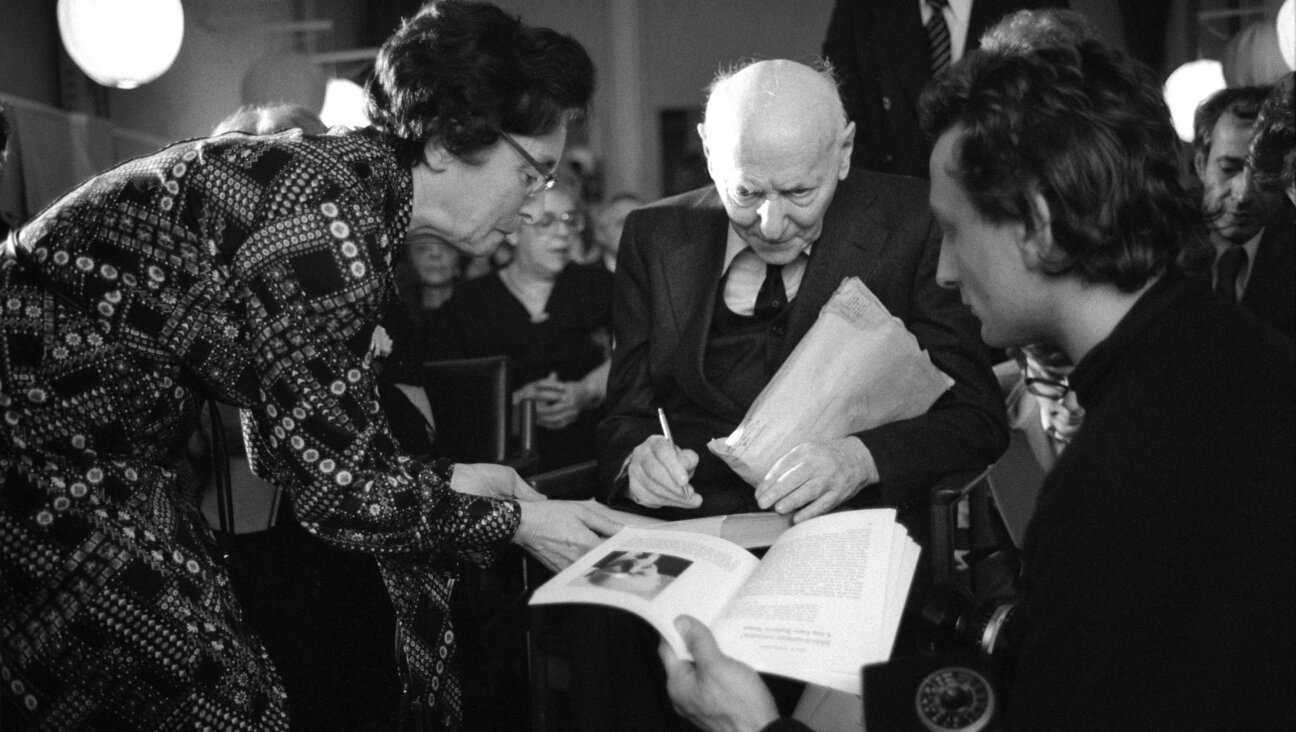

Yiddish יצחק באַשעװיסעס מיינונגען וועגן די אַמעריקאַנער ייִדןIsaac Bashevis’ opinion of American Jews

אין זײַנע „פֿאָרווערטס“־אַרטיקלען האָט ער קריטיקירט זייער צוגאַנג צום חורבן און צו ייִדישקײט.

-

Culture In a Haredi Jerusalem neighborhood, doctors’ visits are free, but the wait may cost you

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.