The Shlemiel as Experimental Mensch

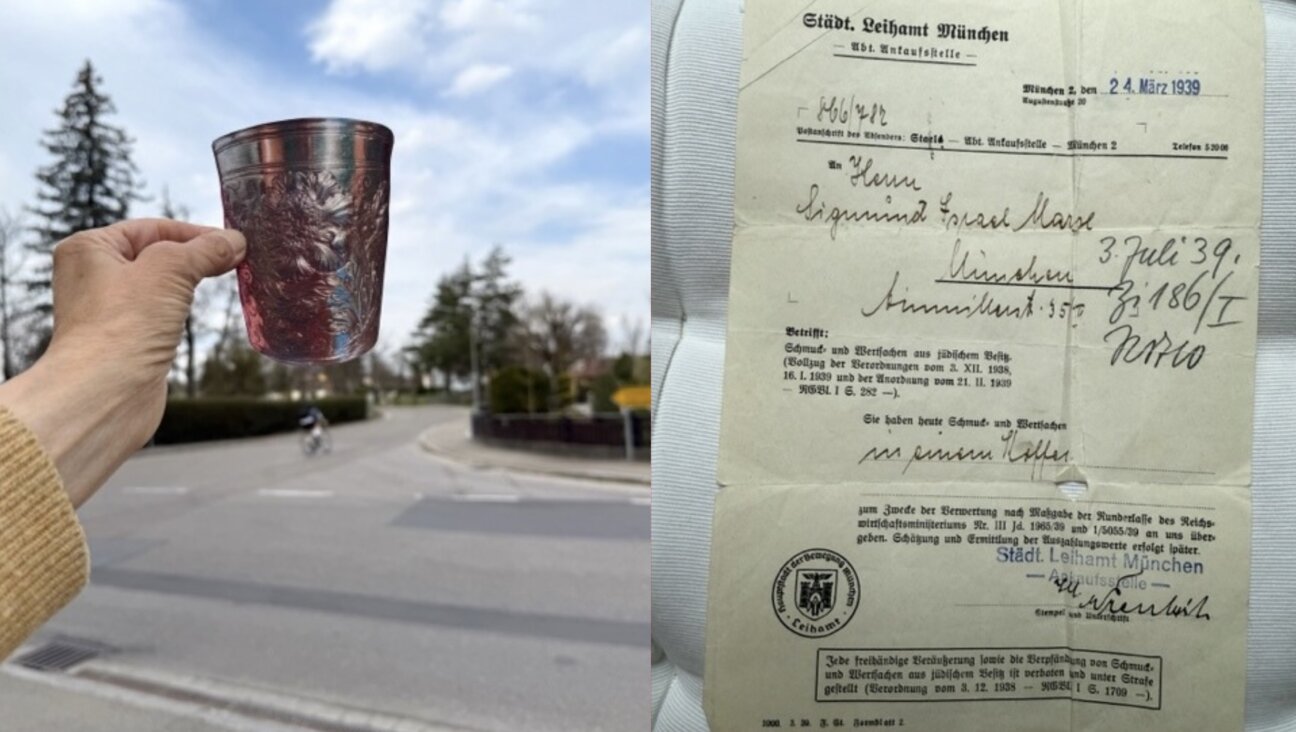

In Bed together: Shlemiel (Michael Ianucci) and his wife, Tryna Ritza (Alice Playten), play dumb and act smart. Image by MICHAEL NAGLE

Isaac Bashevis Singer’s tales are never quite what they seem, and the musical “Shlemiel the First,” adapted from a play that Singer based on his Chelm stories, is no exception in providing surprising depths. Who but Singer could make adultery (at least the characters think it’s adultery) seem so innocent?

In Bed together: Shlemiel (Michael Ianucci) and his wife, Tryna Ritza (Alice Playten), play dumb and act smart. Image by MICHAEL NAGLE

After the final curtain call of its recent short run at Montclair State University as part of Peak Performances, Montclair State’s executive director of arts and cultural programming, Jedediah Wheeler leaped onstage to announce, “This is not the last performance of ‘Shlemiel the First’!” Whether that means another run in Montclair in June, as was hinted to me by the publicist, an off-Broadway run or a run next year at the National Yiddish Theatre — Folksbiene (produced in association with Peak Performances) this show certainly should return and find a larger audience. Although it has tried and failed to get to New York for a “real” run before (it had a few performances in 1994, as part of Lincoln Center’s “Serious Fun” Festival), little ones will love the high energy and fun characters, but older kids — and I include myself and my mother — might be moved on a deeper level.

Like the Chelm stories themselves, the wisdom of fools comes best told by maestros. After 15 years in the wilderness, this adaptation — by the American Repertory Theatre’s artistic director, Robert Brustein — finally may have found its moment. It has pleased audiences at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater and Chicago’s Goodman Theatre among others, but New Yorkers have largely been deprived of its goofy, Broadway-caliber charm.

Brustein has some roots in Yiddish theater, even working in it briefly during the 1950s. And Singer first adapted his children’s stories about Chelm into a nonmusical play called “Shlemiel the First,” which was produced at the Yale Repertory Theatre (founded by Brustein) during the ’70s. It was not a success. Singer told Brustein, “My plays should be done not slow like Chekhov, but fast like Shakespeare.”

Singer’s description of “fast” sparked the seed that grew into the klezmer musical conceived by Brustein, “Shlemiel the First.” Folksbiene’s artistic director, Zalmen Mlotek, who did the arrangements and is the production’s musical director, says that the music is so joyous, “you can’t help but be taken along with it.” Its New York performances in 1994 received raves from, among others, John Lahr of The New Yorker. But in 1995 its Broadway transfer was pushed back to the fall from spring, according to The New York Times, because of “paperwork” surrounding the show’s regional obligations. Then it was canceled altogether. Why?

Blame the Jews. The Jews in Florida, that is, according to Brustein and Mlotek, who composed additional music, some based on folk tunes, to add to Hankus Netsky’s terrific score. In Florida, where it was promoted as the next “Fiddler on the Roof,” Shlemiel the First” flopped. Brustein surmises, in a telephone interview with the Forward, that it pushed buttons for a generation who “wanted to forget Jews ever wore peyes.” Mlotek remembers that it was staged in “barns,” which dwarfed its intimate charm. If the Montclair audiences are any sign, today’s older Jews (many of whom were clearly in attendance) are eager to embrace the Shlemiels, peyes and all.

The director and choreographer of the original, grumpy genius of the downtown postmodern dance scene David Gordon, is once again the director. Mlotek leads a top-notch klezmer band with impressive credits. Directed adroitly around the stage by Gordon, Mlotek and his band embody the music’s role in the play — marching through the action, weaving the characters together before returning to the pit.

The witty, Yiddish-inflected lyrics by Arnold Weinstein are warm but, like Singer himself (as Robert Israel’s gorgeous, crooked sets remind us), have an edge. We first encounter Shlemiel as he sleeps — vertically, against a bed standing up, a visual both funny and practical. His wife, Tryna Ritza, played by Alice Playten, steps away from the bed to complain in “Wake-up Song.” Though Playten is of minuscule stature, her voice is startlingly powerful as she dryly complains about her lazy, sleep-loving husband. She supports the family by selling radishes; her husband’s work as a beadle is poorly paid. “If you can’t be happy with what you’ve got — where is it written that you’ve gotta be happy?” she sings.

As she gets dressed, she dons a robe with sewn-in huge, floppy breasts. The onstage transition and the humor in the add-on big “bazooms,” like the vertical bed, are typical of the theatrical playfulness used throughout. Everything is constantly becoming something else. Sets are changed before our eyes, characters stand on fabric and are pulled offstage gently, sages play their own wives (eight actors play 14 characters) and a dummy plays a wise man. Michael Ianucci’s bear of a Shlemiel delivers humble appeal with top-notch singing.

The upbeat song “We’re Talking Chelm” introduces the “wise men,” a line of six, all wearing overtly fake beards, led by Gronam Ox. Played by high-spirited Jeff Brooks, he has a tendency to say, “I like this idea best; it must be my idea.” But his foolishness is endearing; it’s a poor, silly world, but never bleak. And while there’s mischief — especially from one trickster, Chaim Rascal (chubby, lively Darryl Winslow, who also plays Shlemiel’s demanding son, Mottel, and one of the wise men) — there is no cruelty.

Gronam Ox has summoned Shlemiel to send him on an errand to spread word of his fame around the world. But his departure makes Trina Rytza realize she will miss him. On Shlemiel’s journeys, Chaim Rascal suckers him first into losing his wife’s latkes, and then into returning to Chelm while thinking he’s journeying onward. Shlemiel logically, albeit idiotically, concludes that he’s encountered another Chelm — Chelm the second — where another Shlemiel, who must be Shlemiel the Second — has a life and a wife just like his. And while Shlemiel the Second’s away, Shlemiel the First will play.

As Yenta Pesha, Kristine Zbornik belts “Yenta’s Blintzes” — a lament interrupted by cries of “Gevald!” — about how the treats “you love to squeeze” don’t please her husband anymore. Weinstein’s lyrics provide her with plenty of double entendres and old-fashioned Yiddish expressions to work with, as she ends her marital lament with a classic insult: “The matchmaker who put me with him and him with me should lie in a hospital bed with gallstones. Calling for a nurse. Who’s deaf!”

Act Two explores the nature of identity, mistaken and otherwise. Watching the Shlemiels fall back in love is not only amusing, but also an opportunity to watch Singer (via Brustein) consider how love and sexuality work, and it’s powerful. Naturally, everything unravels at the end. Even Gronam Ox realizes that “dumb is smart” in the upbeat song “Wisdom,” followed by a rousing reprise of “We’re Talking Chelm.”

There are new things for this production, including “Shlemiel’s Song” (which immediately follows his wife’s “Wake-up Song”) and a bravura riff by Shlemiel on all the professions he could never have, which is added to the song “Beadle With a Dreydl.” If the tune seems familiar, it’s because, as Mlotek pointed out to me, it’s the popular Yiddish nigun, or wordless tune, “Chiri Bim.” Ianucci continues into a witty abecedarium of all the jobs a poor Shlemiel could never do (glassblower, for one). In the end, both Shlemiel the character and “Shlemiel the First” are simple on the surface, but a moment in their presence and you realize, like Gronam Ox, that “dumb is smart.”

Gwen Orel is a freelance writer on theater, music and film. She has a doctorate in theater arts from the University of Pittsburgh.

Click here for a discussion of the genesis of the piece with Robert Brustein and Zalmen Mlotek

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Trump administration restores student visas, but impact on pro-Palestinian protesters is unclear

-

Fast Forward Deborah Lipstadt says Trump’s campus antisemitism crackdown has ‘gone way too far’

-

Fast Forward 5 Jewish senators accuse Trump of using antisemitism as ‘guise’ to attack universities

-

Fast Forward Jewish Democratic Rep. Jan Schakowsky reportedly to retire after 26 years in office

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.