What Religious Arguments Are Really About

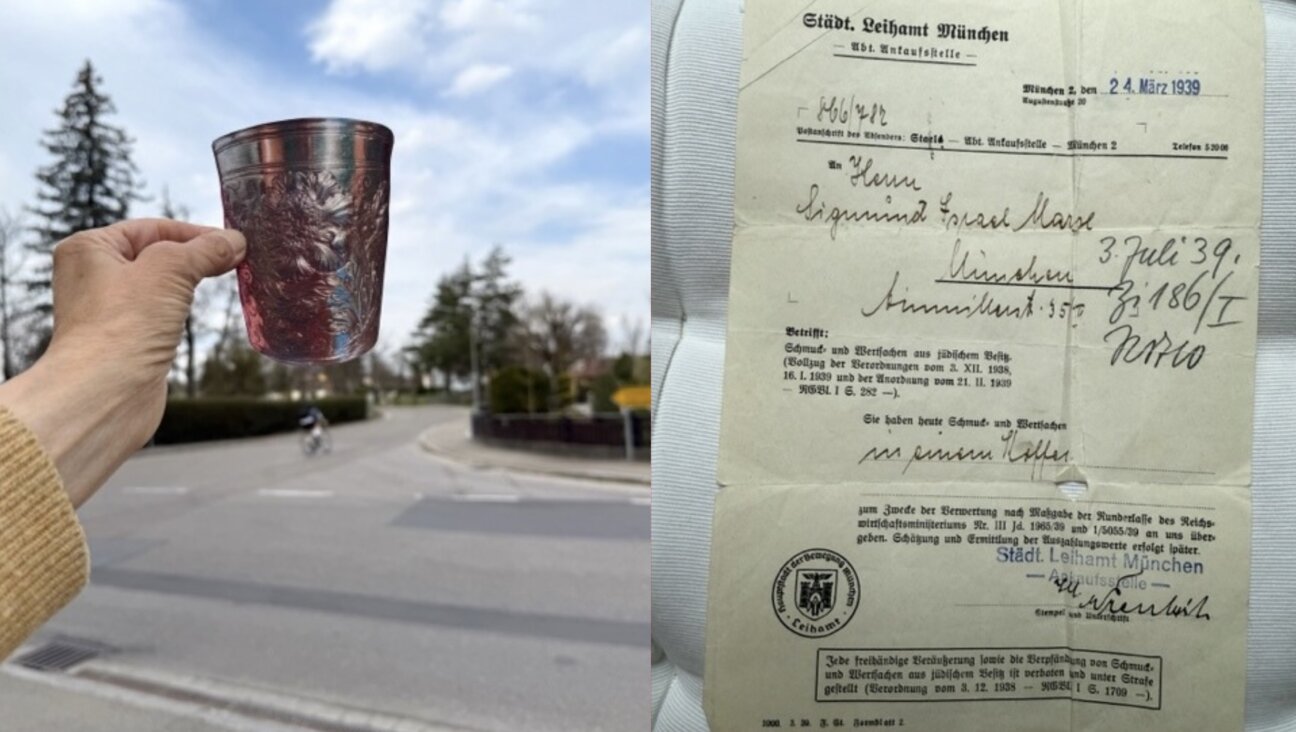

Heart, Soul, Mind: Religion in general, and Judaism specifically, calls on each of these human faculties. Image by Getty Images

‘All of a sudden, there was hope in my heart I’d see my father again.”

Thus wrote one of America’s most influential religious leaders of the moment when he became religious. It was at his father’s funeral, and the presiding minister had just said that death is not the end, that there is an afterlife. The boy was only 10. And he grew up to be Tim LaHaye, evangelist and co-author of the massively best-selling “Left Behind” series, which describes, in gory detail, the rapture that millions of Americans believe to be imminent, when the good will be sorted from — the rest of us.

LaHaye’s remark is telling. He didn’t become convinced of the afterlife because of theological argument — he became convinced because he was a grieving child, and the idea gave him solace. As he grew up, more and more ideas accreted to the experiences of solace, meaning, community and perhaps even the sacred. It was never about the ideas; it was about the pain of living, and the healing one finds in religion.

This is why it is so difficult to talk about religion in America today, why we fight wars about it, why we condemn and even kill one another over it: because it gets us in our guts, and stays there. Religions do present theological doctrine, but what they really offer are solace, love, sanctity and value — all of them inchoate, all of them dear.

And let me be clear: I’m no different from LaHaye. A lonely boy at summer camp, I found “God” in the solitude of nature. As a closeted young adult, I found meaning in the pathways of Halacha. Nor is religion only for the pained; all of us yearn for community, connection and some notion of immortality. Religions provide these things, and we’ll believe anything to maintain them.

Really, why should anyone care so much about the age of the earth, the parting of the Red Sea or the resurrection of Christ? Do we really suppose that the most ardent of religionists are committed to ontology and history?

No — these doctrines are important because of the deep desires to which religion caters. Fundamentalisms and orthodoxies may claim to be about the content of theological propositions, but the reason it’s impossible to argue with their adherents is that they have so much at stake in their views being right that they’ll say or do anything to make it all work out. What’s at stake? If the Torah isn’t literally true, then something in my life is wrong. If Jesus didn’t die for my sins, then I am not okay.

This is how religion works. As those in the Jewish community arguing for “deep, immersion experiences” — from Birthright Israel to Sabbath services, summer camp to senior pro– grams — are coming to realize, religion works by grabbing us where it counts. This is why religion makes so much sense at funerals: because we need it most when our lives seem most fleeting. Indeed, religion often works by means of a curious inversion: precisely by insisting that we are not okay, it constructs a world that is.

The trouble is that for many people, these intense feelings become invisibly translated into beliefs and opinions. America’s religious right has intense religious experiences, and associates them with biblical literalism. The Islamic world’s religious right has intense religious experiences, and associates them with keeping the Ummah (muslim community)pure of corruption and decay. Israel’s religious right has intense religious experiences, and associates them with a holy land and a sacred destiny. In this way, fervent hope leads to fervent ideology.

Our political debates are not about what they pretend to be about — evolutionary biology, civil liberties or pre-existing conditions; they are about a terrified minority, afraid that it is losing all it holds dear.

Biblical inerrancy is not a mere interpretive proposition; it is necessary for the dearest of dreams to be true, for that young boy inside the evangelist to believe he’ll see his father again.

Or, closer to our own tradition, how many of us have felt, at one time or another, that if the edifices of biblical or rabbinic law crumbled, not only our lives but also our very souls would lose structure and coherence? Surely this is the great appeal of Orthodoxy, and the great lack of more liberal Jewish movements: that it all makes sense, even if it doesn’t. That there is a point, a design, a truth at the core of life. Liberal rationales — that the commandments are a path toward God consciousness, or ethical behavior, or social justice — lack that kind of power. And if it can’t make you cry, it’s not religion.

This is why otherwise intelligent people make absurd, ridiculous claims that fly in the face of the scientific revolution. That evolution, among the most successful explanations of facts that has ever been propounded, is somehow incomplete or inaccurate. That a fetus is a baby. That a blastocyst is a baby. None of this is about science; it’s about primal human needs. The mind stuff is just window dressing.

Fundamentally, religion works by saying that “if X, then things are okay.” If you perform the commandments, believe the stories, act in such and such a way, then everything will be all right. In so doing, religion brings light and love to billions of people. Yet it also yokes that light to fervently held propositions.

I am a religious person, in love with God, and a mystic. As my readers know, I think spiritual and contemplative practice makes us better people, and makes life worth living. But when spiritual states become wedded to ideology, they become dangerous. Already, one-third of our country believes itself to be at war not only with Islam, but also domestically, in what used to be called the “culture wars.” Our lunatic fringe has grown in size as the bulwarks of its society have begun to crumble (a black man is president, homosexuals are getting married), and, whether explicitly religious or not, its rage is terrifying.

And we are all implicated by their fury. If I make a political decision based on an irrational or subjective value I hold privately dear, because of the emotional connections I associate with it, I am committing the same sin as they are. Those of us who are religious bear a heightened burden to question our motivations.

Three hundred years ago, John Locke wrote his “Letters Concerning Toleration,” inspired by the English Civil War. In the shadow of that conflict, Locke argued that because religion so stirred up the sentiments, and because its claims could never be arbitrated objectively, religion should have no role in shaping public policy. It’s just too contentious, Locke said, providing what would become one of the core theories for the Enlightenment’s separation of church and state. Locke, of course, was right.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Gaza and Trump have left the Jewish community at war with itself — and me with a bad case of alienation

-

Fast Forward Trump administration restores student visas, but impact on pro-Palestinian protesters is unclear

-

Fast Forward Deborah Lipstadt says Trump’s campus antisemitism crackdown has ‘gone way too far’

-

Fast Forward 5 Jewish senators accuse Trump of using antisemitism as ‘guise’ to attack universities

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.