Jews Have Been Magic for Thousands of Years

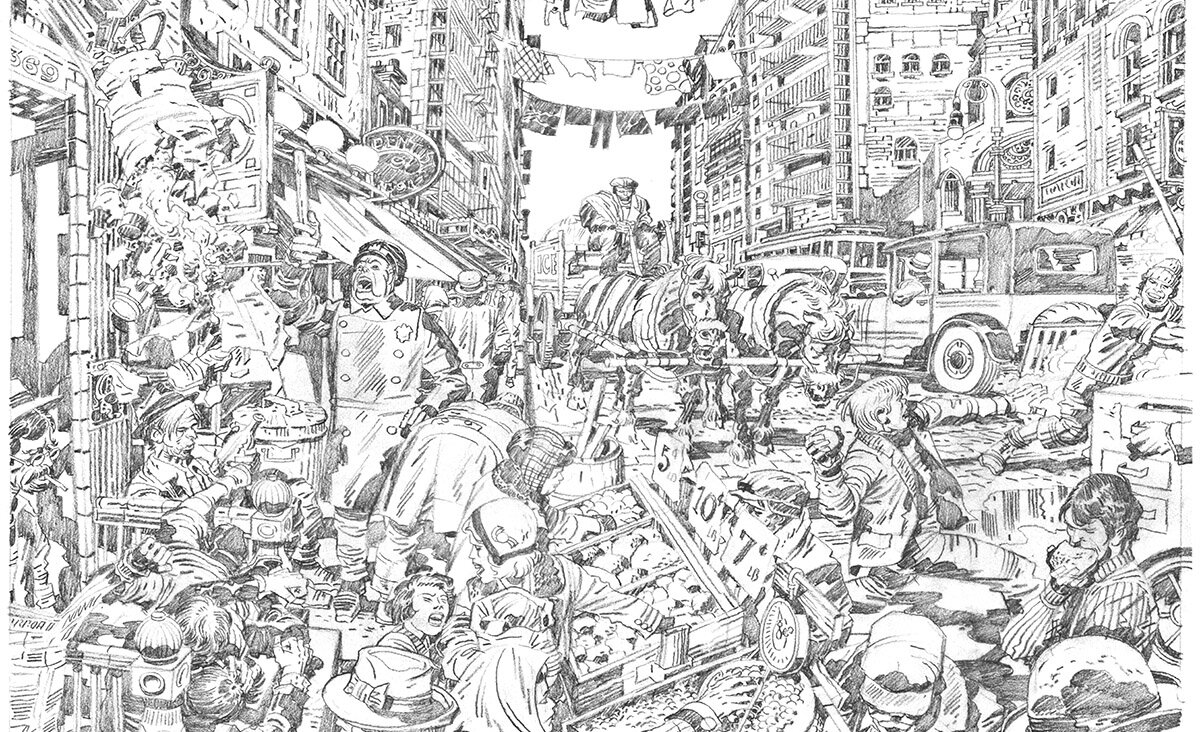

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

We all believe in magic. Despite 300 years of industrial and social revolution, as well as unparalleled explanation of the natural world through the scientific method, we still throw salt over our shoulders, put up hamsas in our homes, wear lucky shirts to job interviews and run through tested game-day rituals, whether we are playing or watching. The new exhibition at the Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem, “Angels & Demons: Jewish Magic Through the Ages,” (open for a year from May 5) shows us how deep-rooted and complex those beliefs are.

The majority of the exhibition, which displays artifacts from North Africa, Byzantium and other locales more geographically appropriate for a museum based on the Bible lands, is of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” order of magic. Items and procedures that the rabbis might not condone, but would probably not go out of their way to condemn; spells to cure disease, charms to protect new mothers or newborn children and amulets to ward off evil or infestation were not religiously countenanced, but did little harm. In fact, the most recent amulet on display (placed next to the most ancient item, from the 8th century BCE at the exhibition’s entrance) is a text with specific instructions for use. This text, written in 1992, cured the owner who every day for a week drank water in which the parchment had been steeped and then wore it in a silver holder until the problem was resolved.

Of course, hamsas and other general amulets for warding off the evil eye have always been balanced by specific prescriptions. Most unexpected, at least to this Northern European Jew, were the inverted clay bowls inscribed with spells and, often, pictures that were placed under the threshold of the house to deter spirits and beasts from entering. These, too, varied between the general (fire, rats) and the specific (the angel Sarfiel orders two demons to be exorcised from the household of Kafnay, son of Imma, and his wife, Immay, daughter of Anay).

Black magic that bends others to your will, only plays a small part in the exhibition. But, enticingly hidden behind a black curtain, are the forbidden tools of manipulative magic: potions, curses and poppet dolls. The details of magical coercion are exotic, but the intentions are almost always banal: Hurt your enemies, and seduce objects of desire. In a rare twist, a carved voodoo doll with bound limbs from the Hellenistic Period in Israel (332 C.E. — 37 BCE), is labeled “probably used in erotic magic practices,” suggesting that some people were aiming to kill two birds with one stone.

Obviously, magical objects are going to look a little strange from the context of the Jewish mainstream. But even beyond this strangeness, the widespread use of pictures and, in some cases, figures gives these Jewish objects the aura of the pagan. Less so for the illustrated magic books collecting recipes, spells and procedures for mitigating a variety of situations. For a people so obsessed with the divinity of the book, the power of letters is second nature even when it is, strictly speaking, prohibited.

One virtue of magicians is that they, like novelists, have a vested interest in making the unknown seem graphic and terrible. Demons are not cute cartoon characters, but rather furious forces of nature to be dealt with in specific ways. In the magical worldview, Lilith is not a powerful feminist icon but a vicious, vengeful demon who devours newborn babies and spitefully kills their mothers. Specific adjurations need to be crafted, alluding to myths describing her weaknesses and previous promises. The anime-sounding Suni, Susuni and Snigli are in fact powerful angels. By a number of different names alluding to the same myths (in other texts they are called Sanoi, Sansanoi and Samangalof), they have the hex on Lilith and are thus the specific spirits charged with protecting houses with babies and mothers in them.

In the end, the main drawback of “Angels & Demons” is its logistical limitations of space and scope. It’s a shame that such a suggestive exhibition couldn’t be spread out more. The surface of the prevalence, pattern and practice of Jewish magic and its context in the larger world of Mediterranean mythology is barely scratched by this worthy introduction. Samangalof and friends come from an entirely alternative mythical system that would surely enrich our understanding of midrashic traditions. The museum is running a series of events that allows collectors, users and current practitioners of the magical arts to shed light on this marginal but very Jewish narrative. Perhaps, with intervention from either side of the black curtain, such a show might become possible in the future!

Dan Friedman is the Forward’s arts and culture editor.